Gas in Venus's atmosphere "very encouraging for the hypothesis of life"

There's something strange happening in the atmosphere of this hellish world.

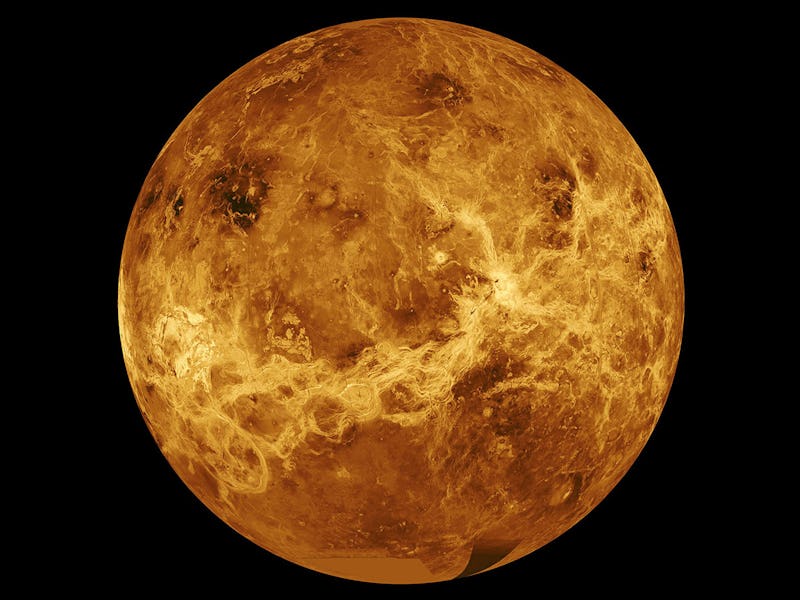

Of all the planets in the Solar System, Venus is the closest to Earth. They are almost the same size, mass, and density. But Venus is way more intense.

The surface of Venus is an inferno, with temperatures reaching up to 900 degrees Fahrenheit, featuring a volcanic landscape, and an extremely dense atmosphere that traps heat. On the shortlist of planets that could potentially host life, Venus rarely makes the cut.

But perhaps we are in for a surprise. In a study published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy, a team of astronomers describes a shocking discovery: Traces of a gas in Venus' clouds typically associated with life on Earth. And they can't explain how it got there.

Using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, scientists detected traces of phosphine gas in Venus' atmosphere. Phosphine is considered a biosignature gas on Earth, meaning that it is typically produced by a living organism.

When searching for signs of life on other planets, scientists look for traces of these 'bio-signature' gases to help them identify if a planet is potentially habitable.

So with all that we know about our nearest planetary neighbor, the presence of phosphine on Venus is rather puzzling, to say the least.

Lead author Jane Greaves, an astronomy professor at Cardiff University, explains the team was deliberately looking for phosphine in the clouds of Venus to test the hypothesis of the planet's habitability.

"With high confidence, we have detected the phosphine on Venus, which was very unexpected and very exciting," Greaves told reporters at a press briefing on Monday. "This is very encouraging for the hypothesis of life, but at the same time we are being very careful."

A hellish world — Venus may be the second closest planet to the Sun, but it is the hottest. This scorching world spins slowly in the opposite direction of most planets, but its winds blow as fast as hurricanes, sending Venus' acidic clouds for a spin around the planet once every five days.

Venus' atmosphere consists mostly of carbon dioxide and traps heat in the same way that greenhouse gases do here on Earth. That's why Venus often serves as an eerie vision of what Earth's future may look like if we don't get greenhouse-gas emissions under control.

Astronomers believe Venus may have looked very different at a point in its early history and may have even had water flowing on its surface. However, as the planet heated up, the oceans evaporated and its surface temperature became so hot that any life would have been destroyed.

For now, scientists still doubt that life, as we know it, could exist on Venus. The conditions on its surface are hostile to any form of life.

However, the temperatures at its clouds are slightly more bearable. And while the clouds contain sulfuric acid, which, again, is not ideal for life to develop, there is a slightly better chance that some form of life could exist in Venus' cloud decks.

The phosphine found in Venus' clouds should have been destroyed by its atmosphere. But the scientists behind the new study found an abundance of 20 parts-per-billion of phosphine in Venus’s clouds — posing a cosmic mystery.

"We are not claiming we have found life on Venus, we are claiming the discovery of phosphine gas, the existence of which is a mystery," Sara Seager, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and co-author of the new study, said during the press conference.

The study runs through different hypotheticals by which the phosphine could have been produced in Venus' atmosphere, but the astronomers still could not determine its likely source.

Instead, the researchers suggest that it may be the sign of an unknown chemical or geological process taking place on Venus which scientists did not deem possible for the fiery planet. It may also indicate a form of life that astronomers and astrobiologists are yet to identify, one able to survive under Venus' extreme conditions.

"There’s some completely unknown and exotic, therefore very exciting, chemistry happening on Venus," William Bains, a researcher at MIT and co-author of the new study, said during the press conference. "Or that the phosphine is produced by some form of life."

Further observations are needed in order to investigate this strange phenomenon and conclude whether or not what's detected is actually a sign of life.

The researchers behind the new study are also counting on future missions to Venus that could further explore the composition of its atmosphere, and examine whether there is a possibility of some form of life that would survive in this scorching hot world.

"At the moment we only have one example of life that we know and that is life on Earth," Bains said. "If we were to find life on Venus, that would be of profound philosophical importance."

Abstract: Measurements of trace gases in planetary atmospheres help us explore chemical conditions different to those on Earth. Our nearest neighbour, Venus, has cloud decks that are temperate but hyperacidic. Here we report the apparent presence of phosphine (PH3) gas in Venus’s atmosphere, where any phosphorus should be in oxidized forms. Single-line millimetre-waveband spectral detections (quality up to ~15σ) from the JCMT and ALMA telescopes have no other plausible identification. Atmospheric PH3 at ~20 ppb abundance is inferred. The presence of PH3 is unexplained after exhaustive study of steady-state chemistry and photochemical pathways, with no currently known abiotic production routes in Venus’s atmosphere, clouds, surface and subsurface, or from lightning, volcanic or meteoritic delivery. PH3 could originate from unknown photochemistry or geochemistry, or, by analogy with biological production of PH3 on Earth, from the presence of life. Other PH3 spectral features should be sought, while in situ cloud and surface sampling could examine sources of this gas.

This article was originally published on