New Study Finally Sheds Light On One of the Universe’s Weirdest Objects

These weird celestial objects can form like stars or planets, but the end result is the same: a gas giant almost big enough to be a star.

It’s not entirely fair to call brown dwarfs failed stars. At least some of them are actually really ambitious planets, a new study suggests.

Brown dwarfs are known amongst astronomers as celestial misfits. They’re too massive to be a gas giant like Jupiter but not quite massive enough to be a star. (For context, the smallest stars are about 80 times Jupiter's mass.) Astronomers often refer to these awkwardly-sized objects as “failed stars” (so rude) since they seem to form as stars do — coalescing out of dense clouds of interstellar gas and dust – but they don’t grow large enough to kickstart nuclear fusion in their cores. But a recent study found at least one brown dwarf that formed like a planet, gobbling up a wide swath of material from the disk orbiting a newborn small star.

That means there’s more than one way to make a brown dwarf, and these dim giants may not be failures after all: Some of them are wildly successful planets.

Caltech astronomer Steven Giacalone presented his work at the 243rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

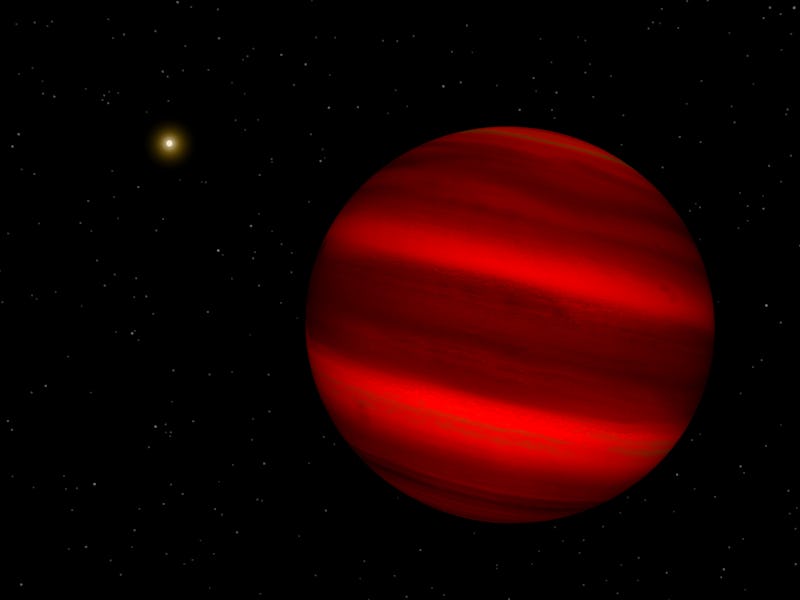

Artist's concept of how the brown dwarf Gliese 229 b might appear from a distance of about a half million miles.

Reach for the stars — you may almost make it

Giacalone used data from the Keck Planet Finder, an instrument at the Keck Observatory in Hawai’i, to study the brown dwarf GPX-1b, a behemoth 20 times more massive than Jupiter (and about a quarter of the size of a red dwarf, the smallest known type of star). GPX-1b orbits a red dwarf star, and Giacalone and his colleagues wanted to know whether the pair had formed from the same stellar nursery (a nebula where new stars are forming) and been caught up in each other’s gravity or whether GPX-1b had formed from the disk of gas and dust around the newborn red dwarf, like a planet.

Brown dwarfs are fascinating objects in their own right since they occupy a murky space between planethood and stardom, but understanding how they form can also shed light on the evolution of small stars and giant planets.

The tilt and shape of one object’s orbit around another can reveal a lot about their shared history. For example, in our own Solar System, Neptune’s largest moon, Triton, orbits the planet backward (in the opposite direction from Neptune’s rotation and the other moons’ orbits), and that’s a clue that Neptune’s gravity probably captured Triton and pulled it into orbit sometime in the past.

In their Keck data, the astronomers saw that GPX-1b’s orbit around its star is lined up with the star’s equator — not tilted at a wild angle That suggests the brown dwarf formed in the disk of gas and dust orbiting the star shortly after its birth — like a planet, in other words.

Brown dwarfs that orbit around their star’s equators probably formed similar to planets, while those tilted at wild angles probably formed more like stars.

If the brown dwarf had formed like a star in the same dense nebula as its host star, the pair would have pulled each other into a close orbital dance (but probably a wild, swinging dance that left them orbiting each other at jaunty angles.) Instead, they promenade around each other with their equators neatly lined up.

“This is only one data point, and preliminary, but it suggests that the brown dwarf migrated close to its companion star in a similar manner to planets,” said Giacalone during his presentation.

GPX-1b is the first time astronomers have ever actually witnessed a brown dwarf that formed like a planet, although models had suggested it was possible. Other brown dwarfs, especially those that orbit farther from their host stars, seem to have formed more like binary pairs in which one partner didn’t quite achieve stardom and is just holding onto the other’s coattails.

In other words, some brown dwarfs are near-miss failures, but others are runaway successes.

This article was originally published on