Scientists Found Evidence of a Massive Solar Storm That Smashed Into Earth 14,300 Years Ago

And near-fossilized tree rings, unearthed in the French Alps, are the keepers of its secrets.

Scientists just found traces of the most terrifying solar storm ever recorded, embedded in ancient trees jutting out of the mud of an alpine riverbank.

Climate and ocean scientist Edouard Bard of the College of France, along with colleagues from Aix-Marseille University and the University of Leeds, found that tree rings dating to around 14,300 years ago contained a huge amount of radioactive carbon, which they say is evidence of a massive solar storm that flooded Earth’s upper atmosphere with charged particles. If they are right, that ancient bombardment would have been the most powerful ever recorded.

Such a huge solar storm would also be a sobering warning about what’s possible in the future, and studying such extreme solar events in the past could help us predict and prepare for them in the future. A study investigating this ancient solar event was published this week in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

Bard and his colleagues matched the rings of trees they found with the rings of other very old trees from nearby, and by lining up those records, they were able to date each growth ring in the trees. This is called dendrochronology, and it can provide a valuable archive of information about the past.

Dendrochronology FTW

A muddy riverbank in the French Alps might not immediately call to mind long-ago solar storms (let alone the prospect of future disasters), but Bard’s team recently found evidence of the most powerful solar storm ever documented, locked inside the wood of trees buried for so long that they’d started to fossilize.

In layers of wood that grew about 14,300 years ago, the researchers found surprisingly high levels of radioactive carbon (carbon-14, the same radioactive isotope that’s used to date ancient materials). There’s always a constant, small amount of radioactive carbon being produced in the upper atmosphere that falls to Earth, which is a good thing because radiocarbon dating depends on it. But the huge amounts of radioactive carbon that Bard found in these ancient tree rings were far above the usual level.

And when they checked layers of Greenland ice from the same timeframe, they found deposits of a radioactive isotope of beryllium. Radioactive beryllium-10 also forms when fast-moving charged particles in the upper atmosphere kickstart certain chemical reactions, and it tends to find its way to Earth in winter snowfalls. Seeing a huge spike in both radiocarbon and beryllium-10 in the same year suggests a bombardment of charged particles from some sort of cosmic event, whether a nearby supernova, gamma ray burst, or, in this case, a solar storm.

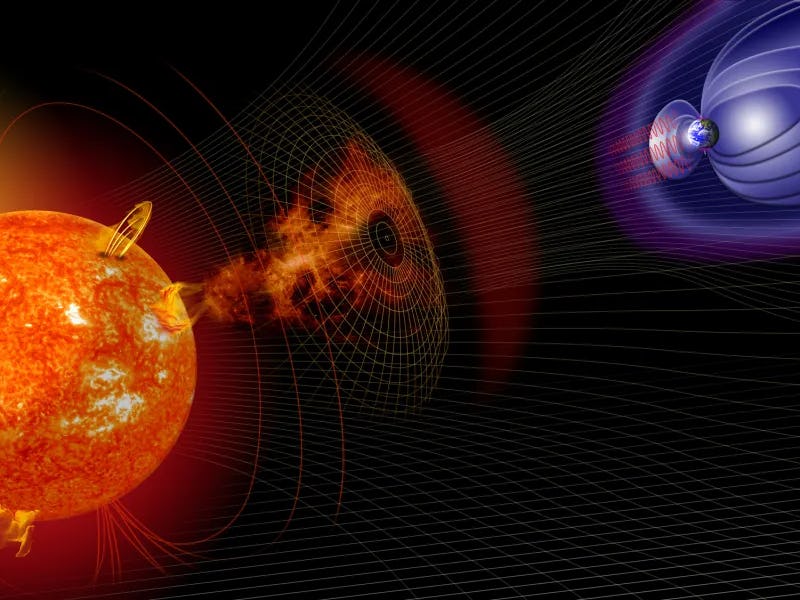

Solar storms occur when the constantly moving lines of the Sun’s magnetic field suddenly reorganize themselves, releasing huge amounts of energy. That violent explosion on the Sun’s surface can fling radiation, and even some of the Sun’s outer layers, out into space. A few minutes later, a fast-moving rain of energy and electrically charged particles smashes against Earth’s magnetic field and upper atmosphere.

What Do Vikings and Victorian Telegraphs have in common?

The magnetic storm triggered by these particles hitting Earth’s magnetic field can interfere with radio and cellphone signals, especially at high latitudes. Charged particles can also damage electronics, especially on satellites in orbit but also on the ground if the solar storm is severe enough. In 1859, for example, a solar storm called the Carrington Event knocked out telegraph service in some areas (and equipment even caught fire at several stations around the world).

The trees in the Drouzet River are what’s called subfossils; they’d started the process of fossilizing, swapping out their squishy organic bits for hard minerals, but the process hadn’t finished. That’s why Bard and his colleagues were able to extract radiocarbon samples from the wood.

Today’s electronics — especially power grids and communications networks — are better shielded than telegraphs in the mid-1800s, but a powerful enough solar storm could still wreak havoc. And we’ve never seen anything like the solar storm that hit our planet 14,300 years ago, according to Bard.

The solar storm that struck in those pre-Holocene days was one of a rare class of disasters called Miyake Events (named after Japanese physicist Fusa Miyake), which are marked by huge spikes in radioactive carbon, beryllium, and chlorine isotopes in the Greenland ice sheet and in ancient tree rings. Miyake Events seem to involve huge waves of cosmic rays colliding with Earth, but scientists still don’t completely agree about what causes them. One cause of a Miyake Event can be a massive solar storm, but other possibilities include gamma ray bursts or supernovae somewhere in our cosmic neighborhood.

Bard and his colleagues lean toward the solar storm theory, and if correct, the 14,300-year-old event they’ve discovered is the strongest of the five Miyake Events that we know of in the past 15,000 years. The last Miyake Event happened in 993 CE, toward the end of the Viking Age; in fact, its effects helped archaeologists date a Norse settlement in North America.

Back some 14,300 years ago, the invention of agriculture was still thousands of years off, so solar storms likely had no impact on our hunter-gatherer ancestors — except for delivering some really spectacular aurorae. But for a modern society that now runs on circuits and silicon, a Miyake Event would be devastating.

It Happened Before, It Can Happen Again

Remember that telegraph-frying solar storm back in the mid-19th century? Well, astronomers actually managed to observe the event that caused it, and now Bard’s work adds to that growing body of devastating solar storm evidence.

“Nowadays, we also obtain detailed records using ground-based observatories, space probes, and satellites,” says Bard. “However, all these short-term instrumental records are insufficient for a complete understanding of the Sun. Radiocarbon measured in tree rings, used alongside beryllium in polar ice cores, provide the best way to understand the Sun’s behavior farther back into the past.”

By studying the solar storms of the past, Bard, as well as other astronomers and dendrochronologists, hope to learn more about its warning signs as well as its frequency. Meanwhile, space missions like the Parker Solar Probe, along with other observatories on the ground, keep a continually close eye on the Sun to learn its inner workings and to spot an impending solar storm.

No longer simple hunter-gatherers, humanity has more than a few high-tech tools to protect us from the next Miyake Event — whenever it eventually strikes.