The Webb Telescope Reveals a Spooky, Skeletal View of a Nearby Galaxy

This image of the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy is the ultimate galactic Halloween skeleton.

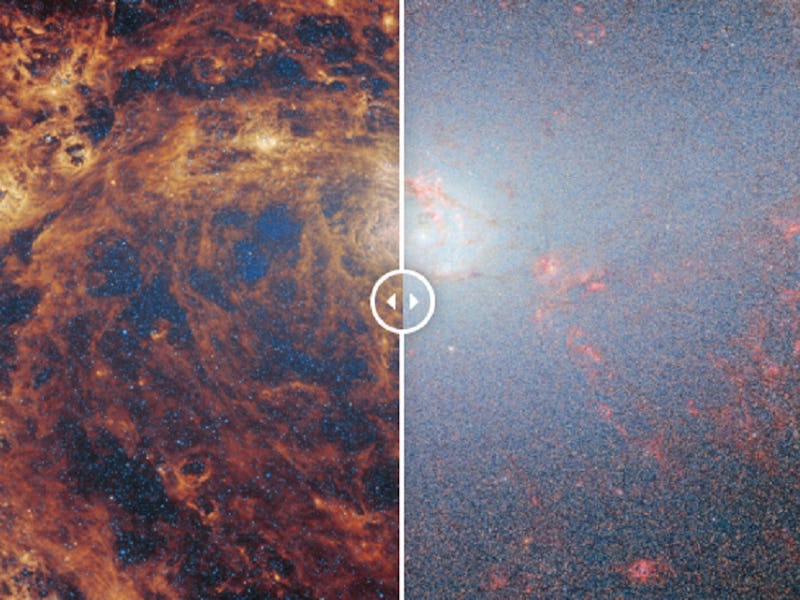

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) captured two views of the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, revealing that galaxies — like ogres and onions — have layers.

So much is invisible to us because our eyes can only see light in a narrow band of wavelengths, between 0.38 and 0.75 micrometers (a micrometer is one-thousandth of a millimeter). But JWST’s instruments perceive the universe in much longer wavelengths called infrared. In infrared, we can see into (and through, depending on the specific wavelengths of light involved) the clouds of gas and dust that block shorter light waves, like visible light. That helps astronomers peel back the layers of a galaxy like the Southern Pinwheel, 15 million light-years away, and see the galaxy’s structure in a whole new light.

What Do Galaxies Look Like on the Inside?

By matching visible colors to each wavelength of infrared light, image processors turned NIRCam data into this stunning image.

JWST’s Near InfraRed Camera (NIRCam) shows M83 in light wavelengths between 0.6 and 5 micrometers long. The image looks staticky and pixellated, but all those tiny specks of static radiating out from the blue-white center of the galaxy to fill the image are actually billions of stars. Those densely-packed stars are mostly older; their younger neighbors show up as patches of bright blue nestled in the reddish threads of gas that trace the galaxy’s spiral shape.

Powerful stellar winds and radiation from those young, temperamental stars have blasted the nearby gas clouds, stripping electrons away from hydrogen atoms and leaving the ionized gas glowing in bright pink.

If you’re located near or south of the Equator, you can spot the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy in the night sky with a good pair of binoculars, but it won’t look anything like this MIRI image.

In even longer wavelengths of light, from 6.6 to 8.7 micrometers long, JWST’s Mid InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) sees the dusty scaffolding of the galaxy in shades of yellow, orange, and red — and this is where it gets weird. The darker reds and oranges are organic molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These molecules form when carbon and other elements bond with the ionized hydrogen in the pink clouds NIRCam revealed.

Yellow tendrils in the dust clouds, where new stars are in the process of forming, trace the galaxy’s familiar spiral shape. The core of the galaxy blazes brightly with its dense population of stars.

To compare these two views of the same galaxy, visit ESA’s website and move the slider and back and forth. Can you spot any of the same features?

On the European Space Agency’s website, you can move a slider back and forth to compare the images; make sure to notice how the bright pink areas of ionized hydrogen in the NIRCam image line up with the bright yellow stellar nurseries in the MIRI version. It’s also worth taking a moment to compare what the galaxy’s bright core looks like in the different infrared wavelengths.

This article was originally published on