Deep-sea mining could power a clean energy future — but there’s a cost

We still know more about the Moon’s surface than the deep ocean floor.

As companies race to expand renewable energy and the batteries to store it, finding sufficient amounts of rare earth metals to build the technology is no easy feat. That’s leading mining companies to take a closer look at a largely unexplored frontier — the deep ocean seabed.

A wealth of these metals can be found in manganese nodules that look like cobblestones scattered across wide areas of deep ocean seabed. But the fragile ecosystems deep in the oceans are little understood, and the mining codes to sustainably mine these areas are in their infancy.

A fierce debate is now playing out as a Canadian company makes plans to launch the first commercial deep-sea mining operation in the Pacific Ocean.

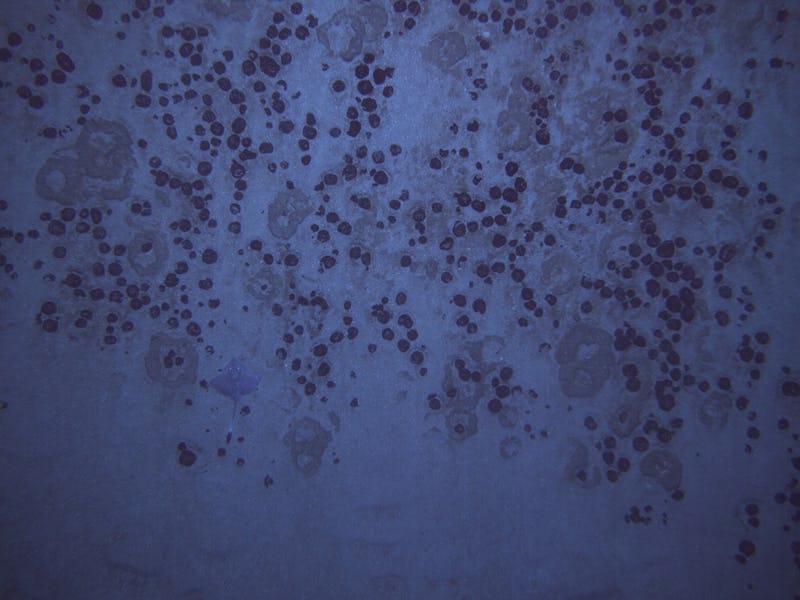

A newly discovered species called Relicanthus daphneae that was found in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone.

The Metals Company completed an exploratory project in the Pacific Ocean in the fall of 2022. Under a treaty governing the deep sea floor, the international agency overseeing these areas could be forced to approve provisional mining there as soon as spring 2023, but several countries and companies are urging a delay until more research can be done. France and New Zealand have called for a ban on deep-sea mining.

As scholars who have long focused on the economic, political, and legal challenges posed by deep seabed mining, we have each studied and written on this economic frontier with concern for the regulatory and ecological challenges it poses.

What’s down there, and why should we care?

Manganese can be found across vast areas of the seafloor around the world.

A curious journey began in the summer of 1974. Sailing from Long Beach, California, a revolutionary ship funded by eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes set course for the Pacific to open a new frontier — deep seabed mining.

Widespread media coverage of the expedition helped to focus the attention of businesses and policymakers on the promise of deep seabed mining, which is notable given that the expedition was actually an elaborate cover for a CIA operation.

The real target was a Soviet ballistic missile submarine that had sunk in 1968 with all hands and what was believed to be a treasure trove of Soviet state secrets and tech onboard.

The expedition, called Project Azorian by the CIA, recovered at least part of the submarine — and it also brought up several manganese nodules from the seafloor.

Manganese nodules are roughly the size of potatoes and can be found across vast areas of the seafloor in parts of the Pacific and Indian oceans and deep abyssal plains in the Atlantic. They are valuable because they are exceptionally rich in 37 metals, including nickel, cobalt, and copper, which are essential for most large batteries and several renewable energy technologies.

These nodules form over millennia as metals nucleate around shells or broken nodules. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone, between Mexico and Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean, where the mining test took place, has been estimated to have over 21 billion metric tons of nodules that could provide twice as much nickel and three times more cobalt than all the reserves on land.

Mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone could be some 10 times richer than comparable mineral deposits on land. All told, estimates place the value of this new industry at some US$30 billion annually by 2030. It could be instrumental in feeding the surging global demand for cobalt that lies at the heart of lithium-ion batteries.

Yet, as several scientists have noted, we still know more about the surface of the Moon than what lies at the bottom of the deep seabed.

Deep seabed ecology

Video from MIT shows the sediment plume created by a nodule-collecting machine during an experiment.

Less than 10 percent of the deep seabed has been mapped thoroughly enough to understand even the basic features of the structure and contents of the ocean floor, let alone the life and ecosystems therein.

Even the most thoroughly studied region, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, is still best characterized by the persistent novelty of what is found there.

Between 70 and 90 percent of living things collected in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone have never been seen before, leaving scientists to speculate about what percentage of all living species in the region has never been seen or collected. Exploratory expeditions regularly return with images or samples of creatures that would richly animate science fiction stories, like a 6-foot-long bioluminescent shark.

Also unknown is the impact that deep-sea mining would have on these creatures.

An experiment in 2021 in water about 3 miles (5 kilometers) deep off Mexico found that seabed mining equipment created sediment plumes up to about 6.5 feet (2 meters) high. But the project authors stressed that they didn’t study the ecological impact. A similar earlier experiment was conducted in Peru in 1989. When scientists returned to that site in 2015, they found some species still hadn’t fully recovered.

Environmentalists have questioned whether seafloor creatures could be smothered by sediment plumes and whether the sediment in the water column could affect island communities that rely on healthy oceanic ecosystems. The Metals Company has argued that its impact is less than terrestrial mining.

Given humanity’s lack of knowledge of the ocean, it is not currently possible to set environmental baselines for oceanic health that could be used to weigh the economic benefits against the environmental harms of seabed mining.

Scarcity and the economic case for mining

The Democratic Republic of Congo produces 60 percent of the global supply of cobalt.

The economic case for deep seabed mining reflects both possibility and uncertainty.

On the positive side, it could displace some highly destructive terrestrial mining and augment the global supply of minerals used in clean energy sources such as wind turbines, photovoltaic cells, and electric vehicles.

Terrestrial mining imposes significant environmental damage and costs to the human health of both the miners themselves and the surrounding communities. Additionally, mines are sometimes located in politically unstable regions. The Democratic Republic of Congo produces 60 percent of the global supply of cobalt, for example, and China owns or finances 80 percent of industrial mines in that country. China also accounts for 60 percent of the global supply of rare earth element production and much of its processing. Having one nation able to exert such control over a critical resource has raised concerns.

Deep seabed mining comes with significant uncertainties, however, particularly given the technology’s relatively early state.

First are the risks associated with commercializing new technology. Until deep-sea mining technology is demonstrated, discoveries cannot be listed as “reserves” in firms’ asset valuations. Without that value defined, it can be difficult to line up the significant financing needed to build mining infrastructure, which lessens the first-mover advantage and incentivizes firms to wait for someone else to take the lead.

Commodity prices are also difficult to predict. Technology innovation can reduce or even eliminate the projected demand for a mineral. New mineral deposits on land can also boost supply: Sweden announced in January 2023 that it had just discovered the largest deposit of rare earth oxides in Europe.

In all, embarking on deep seabed mining involves sinking significant costs into new technology for uncertain returns, while posing risks to a natural environment that is likely to rise in value.

Who gets to decide the future of seafloor mining?

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which came into force in the early 1990s, provides the basic rules for ocean resources.

It allows countries to control economic activities, including any mining, within 200 miles of their coastlines, accounting for approximately 35 percent of the ocean. Beyond national waters, countries around the world established the International Seabed Authority, or ISA, based in Jamaica, to regulate deep seabed mining.

Critically, the ISA framework calls for some of the profits derived from commercial mining to be shared with the international community. In this way, even countries that did not have the resources to mine the deep seabed could share in its benefits. This part of the ISA’s mandate was controversial, and it was one reason that the United States did not join the Convention on the Law of the Sea.

With little public attention, the ISA worked slowly for several decades to develop regulations for the exploration of undersea minerals, and those rules still aren’t completed. More than a dozen companies and countries have received exploration contracts, including The Metals Company’s work under the sponsorship of the island nation of Nauru.

ISA’s work has started to draw criticism as companies have sought to initiate commercial mining. A recent New York Times investigation of internal ISA documents suggested the agency’s leadership has downplayed environmental concerns and shared confidential information with some of the companies that would be involved in seabed mining. The ISA hasn’t finalized environmental rules for mining.

Much of the coverage of deep seabed mining has been framed to highlight the climate benefits. But this overlooks the dangers this activity could pose for the Earth’s largest pristine ecology — the deep sea. We believe it would be wise to better understand this existing, fragile ecosystem better before rushing to mine it.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Scott Shackelford, Christiana Ochoa, David Bosco, and Kerry Krutilla at Indiana University. Read the original article here.

This article was originally published on