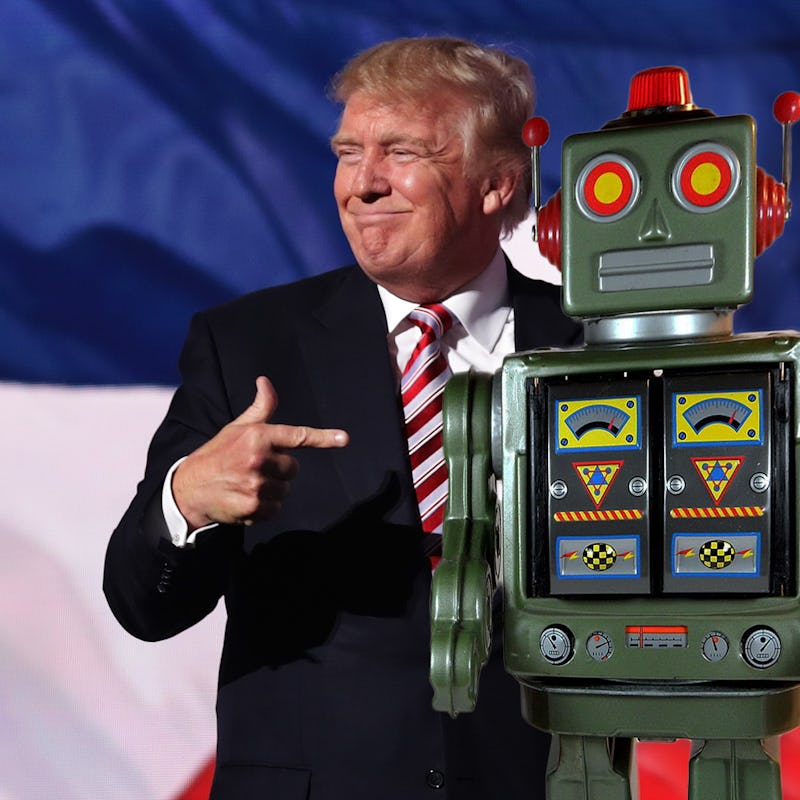

Trump Voters Don't Sweat Robot Outsourcing

As long as the robots are American, we're good.

Ask Dennis Krause about robots, and he’ll talk to you for as long as you like. Having worked as an engineer for 30 years, the bulk of them at Lucent Technologies, Krause has a lot of thoughts about automation and what the future of work looks like in the United States. But Krause doesn’t fear the fourth industrial revolution. Despite all the talk of machines taking human jobs, Krause is generally optimistic about the role of automation in manufacturing.

“Automation is great, its the future, and it helps in dangerous situations,” Krause told Inverse while standing in the middle of a Donald Trump rally in Manchester, New Hampshire. “You’ll still need people to control the automation. You still need staff for maintenance. Those types of jobs will always be here.”

The rally, held on October 28 inside the Armory Ballroom at the Radisson Hotel, came near the end of a campaign Trump made largely about bringing manufacturing jobs back to America. Trump’s biggest promise has been to reverse outsourcing (the “trade” section of his campaign website mentions manufacturing three times, all in relation to U.S. corporations shipping jobs abroad), but his jeremiads against Chinese labor often ignore this modern truth: China is automating its manufacturing workforce. Chinese laborers aren’t replacing American workers; Chinese robots are. Foxconn, which builds Apple’s iPhone and iPad hardware, announced its intention to replace 500,000 mainland Chinese workers with a million robots in 2011. The company announced this month that it is four percent of the way to its goal. The company now manufactures both consumer technology and “Foxbots” designed to replace its labor force.

You’d think this creeping automation, not creeping Sharia, would concern Trump’s base, but as long as robots are in America, they seemed comfortable with the idea.

Krause was one of more than 15 people Inverse interviewed over the course of the afternoon about automation’s growing role in factories and how robots are filling manufacturing jobs (it’s happening in the service industry, too, with developments like a room service robot). Most agreed that more on-the-job automation was inevitable and largely positive, but that there would need to be additional training for displaced workers. Several Trump supporters said that there will always be a need for humans to repair and supervised automated assembly lines.

A common theme in Trump’s rhetoric — which is not reflected in his policy — is that he is a champion of the common person. And looking to the future, there are a lot of low-paying jobs that could be turned over to machines. Earlier this year, a White House report predicted that many workers who earn under $20 an hour could eventually be replaced by robots, a risk that plays out across industries.

“Automation tends to replace low-wage jobs with high-wage jobs,” James Bessen, a lecturer at the Boston University School of Law who researches the effect of innovation on labor, told the Los Angeles Times in September. The people whose skills become obsolete are low-wage workers, and to the extent that it’s difficult for them to acquire new skills, it affects inequality.

Todd Misiaszek, left, and Dennis Krause, right. It's not the robots they're worried about, it's the taxes.

And the number of peopled replaced by robots is only going up. A recent study found that by 2021, industrial and factory automation could reach more that $221 billion in global revenue.

But Krause says that high taxes, not robots, are the problem. His friend, Todd Misiaszek agreed. “We need to cut corporate taxes, and unleash the unlimited energy we can produce domestically,” he explained before repeating a phrase made popular eight years ago by Sarah Palin: “Drill, baby, drill.”

Nearby, Joe Cappucci, smiling out from under a Boston Red Sox cap, offered a harsh assessment of trade agreements he blames for sending jobs overseas, but noted that while automation continues to crowd out humans, he’d like to see that automation being done in the United States, not abroad.

Joe Cappucci: As long as the robots are in America, he's good.

“We’ve become a service economy, Capucci says. “We gotta start making shit again.”

Cappucci works in financial planning, and says he’s out several nights a week talking with families who are struggling to put money aside for retirement while still having enough to pay the bills every month. By contrast, his father, who worked at a General Motors plant, was able to “retire with dignity.”

“Automation is generally a good thing if you educate workers,” said Ian McCormack, who is attending graduate classes online at The Citadel. He pointed out that when steam ships took the place of sailboats, people who made sailboats lost their jobs. But that wasn’t bad for the economy or for the country.

A Trump supporter named Sharon, who declined to give her last name, said that the bakery she works at has been significantly automated. These days she supervises production. Though she believes there will always be a need for at least some human oversight, she grudgingly admits that automation has the potential to negatively affect her economic status.

“I appreciate it, but I don’t want too much of it,” she says. “Because then there goes my job.”

Robots in Tesla's auto-production facility.