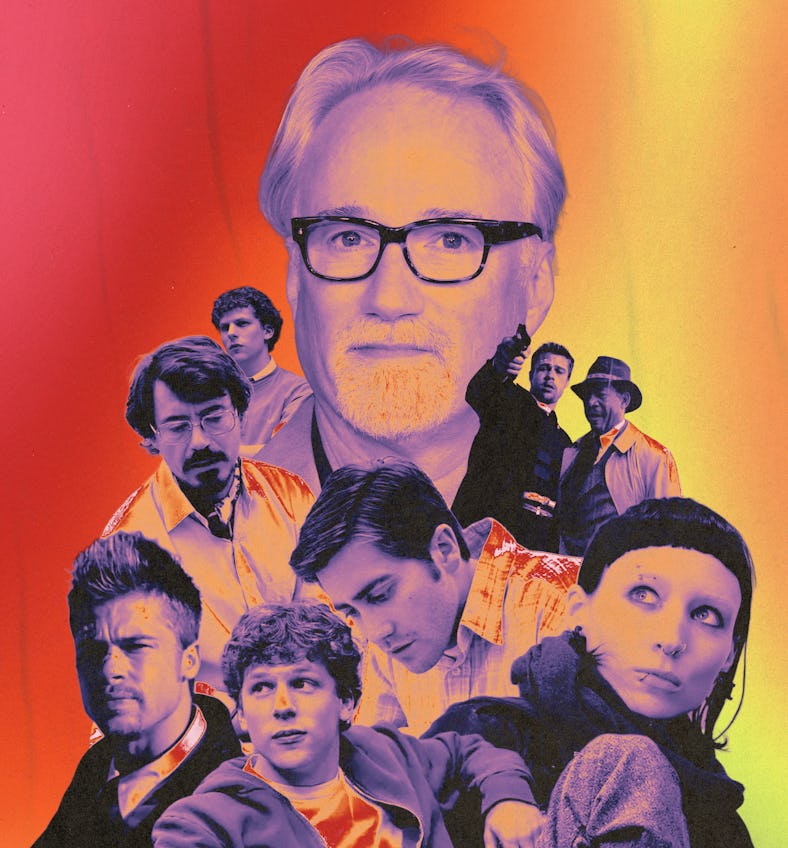

What’s In The Box? The Cold Comfort And Cozy Gloom Of David Fincher

From Gone Girl to Se7en, David Fincher's thrillers are horrific... and oddly comforting.

It was a December evening I’ll never forget: Dark and gloomy, the kind made all the gloomier by a draining shift at a dead-end retail job. The holiday season was fast approaching — and despite my love for Christmas, I didn’t feel much like celebrating. Instead of a feel-good Christmas classic, I found myself craving a different kind of film. I wanted The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

The 2011 film, directed by David Fincher, should not be anyone’s first choice for a holiday comfort watch. It was literally touted as the “Feel-Bad Movie of Christmas” in its cheeky ad campaigns, and its subject matter honored that brief to the letter. I can vividly remember the queasy feeling I was left with on my first watch, as expert hacker Lisbeth Salander (Rooney Mara) and slightly yuppie journalist Mikael Blomkvist (Daniel Craig) entangled themselves in a stomach-churning murder mystery. Their misadventure is trademark Fincher: grimy, gruesome, and downright depressing. I never thought I’d have the constitution to see it again; until that dark and gloomy December evening, it felt like the only thing qualified to cheer me up.

For all my squeamishness, I’m not the only one inexplicably drawn to Fincher’s disturbing filmography. The director is, ostensibly, most at home telling horror stories — but he lays out all that existential terror in a way that’s unmistakably soothing. Is it a morbid curiosity that draws us to Fincher? A symptom of our desensitization to the darkest corners of pop culture? The answer’s more complicated than we think, but it connects the director, and his genre of choice, to a coping mechanism as old as storytelling itself.

Fincher’s Cozy Crime Thrillers

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo was marketed as the “Feel-Bad Movie of Christmas.”

Few can tell a crime story quite like David Fincher. For the past three decades, the director has carved a niche out of dreary, even depressing, subject matter. His first original film, Se7en, established his dark and twisted vision in 1995. He’s only waded deeper into the genre since; ironically, though, his films have become a source of comfort for so many of his fans in the process.

Entertainment critic Allison Picurro compares Fincher’s The Social Network to “a warm blanket draped over my shoulders.” The film is comparatively tame next to Se7en, Zodiac, or The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo — each of which explores the dark, dirty underbelly of crime with cold, calculating precision — but even that triptych carries a level of comfort for her.

“Perversely, the first word that came to mind when I [heard] the names of these three films was ‘cozy,’” she admits to Inverse.

It’s tough nailing down what exactly it is about Fincher that elicits such a response from his viewers — what makes Se7en such “an overwhelmingly seductive movie,” Zodiac “so hypnotically rewatchable,” and the short-lived Netflix series Mindhunter so “weirdly, freakishly pleasant.” The director never shies away from harrowing subject matter, with most of his films focusing in some way on serial murder. They also directly interrogate our collective curiosity with genres like true crime, creating an experience that challenges more than it titillates.

Kevin Spacey’s John Doe, the bogeyman of Se7en, is cut from the same cloth as the “messianic murderers” that fascinated and terrified the world in the ‘90s, but his crimes are impossible to glamorize. He haunts the film’s unnamed city like a specter, delivering a gruesome form of judgment to those who most embody sins like envy, sloth, or vanity. In a decade overwhelmed by post-industrial rot and punk-rock sleaze, his crusade was a kind of wake-up call. Not even William Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and David Mills (Brad Pitt), the detectives tasked with taking him down, get out unscathed. It makes Se7en half-procedural, half-horror film, providing a laundry list of reasons to repent and turn away from false idols like Jeffrey Dahmer and Ted Bundy.

Like many true-crime thrillers, Se7en offers its fans a sense of release in a “safe” space.

Zodiac, meanwhile, tackles the frenzy for serial murderers from a different angle. Following the rise of the Zodiac Killer and the mystery that eluded the San Francisco Chronicle for decades, it directly confronts our present-day obsession with the nation’s most salacious criminals. As the killer was never actually caught, Zodiac denies us any tidy emotional resolution, embracing the dread and disappointment of a mystery unsolved. Yet the precision of this procedural creates a soothing effect for its audience, making for another film that fans can’t help but rewatch again and again.

Fincher’s detached obsession with the details acts almost as a buffer for the straightforward horror in his filmography. From Dragon Tattoo, Zodiac, and Se7en, we get the best of both worlds: elevated, cerebral thrills couched within stories that even Fincher describes as “grungy” and disturbing. As he explained in an interview with Letterboxd, his filmography is “about utter and total loss of control.” Sure, but if you rewatch those films religiously enough, their unpredictable twists eventually give way to a familiar, comforting formula.

That formula is a feature of the horror genre at large. A study from Frontiers in Psychology revealed that horror fans use the genre as a coping strategy to deal with anxieties that may be beyond their control in real life. Repeat exposure to “threatening stimuli” creates a filter through which to explore our fears: the more familiar we are with a subject or story, the less afraid we are, and the more we enjoy the story unfolding before us.

The Comfort of True Crime

Ted Bundy's image on a television screen on the lawn of the Florida State Prison.

Horror obviously isn’t the only outlet for exploring our fears: It’s got stiff competition in the realm of non-fiction. The lure of true crime has long prevailed, but in the past 20 years it’s become something people seek out with a vengeance. The bulk of that consumption lives within the podcasting industrial complex: A 2024 study by Edison Research shows that half the U.S. population binges true-crime podcasts. Shows like My Favorite Murder and Serial created a new kind of cottage industry in the 2010s, and in the years since, true-crime content has saturated the market entirely.

There’s now an unlimited selection of stories to choose from within the genre. Investigation Discovery and Oxygen have molded themselves into “24/7, 365-day diners” for true-crime content on cable, while streamers like Hulu and Netflix churn out a steady stream of “prestige” dramatizations for those in search of more elevated pleasure.

True crime has always walked a dangerous line, especially with the stories that attempt to make sense of notorious murderers like Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer. These stories may indulge the darker parts of our psyche, stoking the violent instincts we push away without encouraging us to act on these urges. On another level, serial killers pose less of an immediate threat post-millennium, with, by some estimates, 80% fewer serial killers than in the ‘70s, and an increase in more clear and present mortal dangers.

“We tend to think of the serial killer as an evil that we’ve already figured out,” writes Tori Tefler in Vulture. They’re almost quaint compared to the horrors plaguing us in this century: violent nationalism, the rise of fascism, and mass shootings, to name just a few.

The popularity of Netflix true-crime dramas prove there is always an appetite for these stories.

True crime stories about said serial killers, then, have become a way to soothe and distract, especially now that sites like Reddit and TikTok have stepped in to connect the true-crime community more intimately. TikTokers and amateur sleuths have taken up podcasters’ crusades by recentering these stories on victims. They’ve doubled down on the bingeability and nostalgia powering the industry. Short-form videos have made consuming true crime all the more convenient, and all the more cathartic. True crime has a way of guiding us through trauma, allowing us to process uncomfortable memories and control what we can’t in real life.

P.E. Moskowitz detailed their experience with true crime in Mother Jones, and the ways it allowed them to process their trauma after a life-changing event. In 2017, Moskowitz attended a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, when neo-Nazi James Fields drove his vehicle into a crowd of protestors, injuring dozens and killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer. Moskowitz turned to true crime to combat the “crushing anxiety and fear” that manifested after the fact, “fear of leaving my house, fear I could die at any moment, fear that the world was collapsing and there was nothing I could do about it.” Podcasts like Serial — and later, some that offered even “trashier and gorier” tales — gave Moskowitz an outlet to process that fear on their own terms.

“True crime made me feel safe,” wrote Moskowitz.

It’s the same for so many people, women especially. According to Dana Dorfman, Ph.D., psychotherapist and co-host of the podcast 2 Moms on the Couch, true crime appeals exponentially more to women than men. “Women are statistically more victimized,” Dorfman told Yahoo! in 2024. “Exposure to such scenarios help women prepare themselves, learn ways of self-defense or self-protection.”

In a world where happy endings are in short supply, especially for women living their day-to-day lives in fear, it’s easy to see why that brand of catharsis proves so addictive — but also dangerous.

“The failings of true crime podcasts do not lie in their basic premise — that women are harmed by men — because that is undoubtedly true,” Moskowitz explained. “The problem is in their assumption that increased awareness, surveillance, policing, and imprisonment are the remedies.”

In manufacturing a safer kind of reality, have we trained ourselves to ignore the nuances of real life? True crime makes no “political or moral demands” of us, and that’s in part what makes its consumption such a slippery slope.

Why Fincher Scratches That Itch Best

Anne Hathaway’s favorite rom-com.

True crime, and stories that follow the true-crime formula, aren’t going away any time soon. As Kyle Heiner — copywriter, Gone Girl superfan, and student of suburban noir — tells Inverse, the genre has always had a grip on American culture. “It first sparked America’s fancy with Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, [then turned] to broadcast television around the turn of the century,” he says. Now we have “the endless barrage of docuseries and limited series reenactments on streamers,” creating a self-soothing experience that’s hard to break away from. “Once you start, you can’t stop.”

That is, unless you have a measured alternative. Heiner’s seen Gone Girl, Fincher’s sardonic story about a marriage on the rocks, “at least 10 times.” He’s built his Letterboxd account around the film and its femme fatale, Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike), whose iconic, icy performance landed her on the Mount Rushmore of “good for her” cinema, a subgenre of cathartic female-driven revenge films.

“What I love about Gone Girl is its satirical approach to the matter,” Heiner adds, “makes everyone, especially the American audience, look the fool.”

The central relationship in Girl With the Dragon Tattoo offers a buffer against the movie’s harsher elements.

There are echoes of that in Se7en and Zodiac as well. Fincher knows we can’t look away from tragedy or violence, however gruesome. So he depicts it all in a way that keeps the audience accountable. We consume true crime because it gives us a sense of resolution, of solving a crime, no matter how old it is. Fincher’s filmography gives us no such satisfaction: His heroes are constantly chasing a reward that never comes. Their respective obsessions lead them to emotional and moral dead ends. These stories are grueling challenges, the meat and potatoes compared to the junk food of true crime.

Despite that subversion, audiences still get the same cozy feeling in Fincher’s work that they do from true crime. Perversely, I find even more comfort and catharsis from The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo — a film I now feel compelled to throw on whenever the weather turns chilly — than the odd true-crime podcast. Fincher couches an abhorrent tale of corruption and violation within an intoxicating, unreal world. The chilling silhouette of a Swedish manor blending into a blanket of snow, faded photographs of missing women, and sparse dark hallways are just a few of the images that are impossible to shake, rendered in the mossy greens, icy blues, and sickly yellows that now represent Fincher at his prime.

The director’s visuals make for an effective shorthand; in a way, it has the same effect as the soothing narration of an otherwise gruesome true-crime story. Each is a vehicle to help us process the unimaginable, couching heightened horror within a world we can process with ease. They’re two sides of the same coin: Whether you take comfort in nihilism or a black-and-white morality play, it doesn’t hurt to indulge in some form of relief.