Neither Biden or Trump were ready for the election's surprise issue

In Pennsylvania, critical to the election, both back fracking in the pursuit of natural gas — consequences be damned.

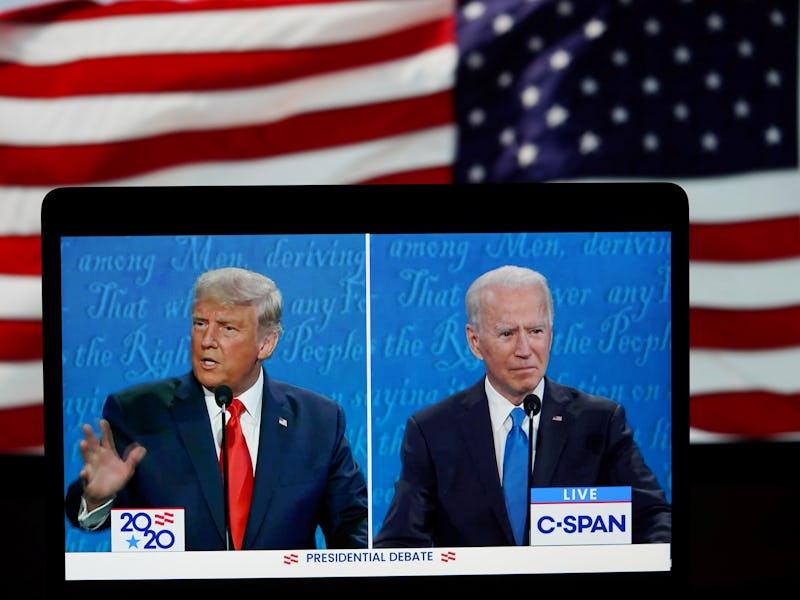

There was no debate over one topic during the 2020 election season, at least after the primaries. There was only a meta-argument, with President Donald Trump arguing that his opponent Joe Biden wanted to ban fracking and Biden strenuously arguing that he did not want to do that. Biden, you see, was only opposed to fossil fuel leases on public land.

For all the hubris of the 2020 election, the fracking meta-argument stands out because of how each side tried to frame an agreement as a disagreement. When the race winnowed to Biden and Trump, there was no place to ask — is fracking good for the people who live near it, good for the local economy, good for the country?

President Trump and Joe Biden spent considerable energy discussing fracking.

What's fracking? — Rock formations have sat on the Earth, mostly undisturbed, for millions of years.

To pick one rock formation, it’s estimated that the Marcellus Formation is 384 million years old. During its earliest days, it trapped millions of ancient microorganisms within oxygen-free rocky tombs. As the years turned to millennia, these microorganisms transformed into what are known as hydrocarbons, the lightest of which have a gaseous form and are what we refer to today as natural gas.

To get that natural gas out of the Earth, engineers drill the rock from the side. Then water, sand, and chemicals violently blast the rock, creating creases that allow for hydrocarbon capture. This technique, formally known as hydraulic fracturing, has been around for some time.

The Marcellus Shale exists under land used for a wide variety of purposes, including farming.

Early attempts were made in the 1860s, and the process began to rapidly expand a century later, starting in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The process doesn’t give off carbon dioxide like coal plants, allowing for many to view it as a “bridge” energy source between fossil fuels and green energy.

Why don't people like fracking? — It’s hard to divorce environmentalism from politics these days, but the issue of fracking emerged as something contentious in the American consciousness after the documentary Gasland came out in 2010. Gasland, directed by Josh Fox, highlights issues that have haunted the natural gas industry ever since:

- Chemicals from the fracking process leaking into the public's drinking water

- Air-polluting methane escaping through the rocks in the ground

- Increased seismic activity

Fracking has drawn widespread protests.

Many of these problems found validation in a Pennsylvania grand jury report from June 2020, commissioned by the state’s Attorney General, Josh Shapiro.

The report ranked the state’s Department of Energy Protection over hot coals, citing a “revolving door” relationship with the natural gas industry created an environment where health concerns were ignored for years.

Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro, a major critic of the state's fracking practices.

“Giant fracking companies were given a free pass by unprepared agencies, and the public was harmed, plain and simple,” Shapiro said in a press conference. Interviews with 75 families and over 30 DEP employees showed a large gulf between constituent and government.

Dirty water is a central theme of fracking protests.

“DEP’s failure to collect data, and resistance to sharing what data they have, coupled with their narrow approach to testing when determining whether contamination has occurred, enables the industry to ignore residents’ claims that oil and gas activity has contaminated their environment, air, or water supply. DEP’s failure to adequately respond to homeowners’ concerns builds distrust between the community and the government,” the report says.

This failure eventually became “entrenched” in the state, according to the report, “which further impedes a meaningful response to the problem.”

While the report offered a number of reforms, from demanding transparency on all chemicals used during the fracking process to transferring some of the DEP’s authority to Shapiro’s office, there is no quick solution to the entrenched gap between what the public and what top scientists know about fracking.

This gap also made itself apparent in the scientific literature. Noting the lack of historical research into the environmental and health effects of fracking in their 2019 paper studying the subject, Irena Gorski and Brian Schwartz acknowledge that “delay is inherent after the introduction of new industries, but hundreds of thousands of wells were drilled before any health studies were completed.”

Like any number of other industries, fracking was able to embed itself onto the American landscape before people had a full understanding of either the physical, environmental, or mental straits it might place people, and then was able to present itself as invaluable.

A rural Pennsylvania teacher, discussing in 2012 how her relationships in a small town frayed when she came out against fracking, suggested that they “all want to be like the couple of families that got rich” off selling fracking rights underneath their land to natural gas companies.

Other members of the town said that the money went to improving local schools and that the natural gas companies were able to fix major problems.

The future of the oil and gas industry remains uncertain, with mostly downward signals.

What happens next? — The 2020 fight over fracking saw Trump attempting to pick up this divide as a wedge issue, a Democratic consultant told NPR recently, similarly to manufacturing in Ohio, coal in West Virginia or Kentucky, or abortion in the South.

It’s a belief rooted in a “partial truth,” Pittsburgh-based author Eve Andrews recently commented in an essay in Mother Jones: “A belief that the wealth that steel and coal and gas brought to the region, albeit years and years ago, is owed a certain respect.”

No matter who wins the election, fracking will continue. Trump might want to invest in the industry if he wins, but that comes with its own challenges: investing in drilling can often mean investment in automation, which lowers the number of people hired in drilling.

If Biden wins, the former Vice President promises “banning new oil and gas permitting on public lands and waters.” While public land use is a concern, this offers no comment or change needed for fracking on private lands, where it could affect families and communities.

Despite the presidential seal of approval, the future might not be bright for fracking. Oil and gas extraction took massive personnel hits through the Covid-19 pandemic, with approximately 107,000 layoffs. Analysts at Deloitte warn that around 70 percent of those jobs “may not come back by the end of 2021 in a business-as-usual scenario.” Of those with jobs, 53 percent don’t feel that they have job security.

While the fracking debate has a number of unique aspects, Covid-19 has shown it in many ways to be an industry like any other. Hobbled by a pandemic, the industry seems to be falling haphazardly while green energy jobs seem to rise. If ever there was a time for fracking to change, the next four years might be it. Just don’t expect that change to come from the Oval Office.