What is a Wormhole? Why is a Wormhole? Why Should You Care?

Finding a spacetime aberration and figuring out how it works could change our understanding of and access to the universe.

Wormholes are far more familiar to people as plot devices than physical phenomena. Narratively’ they’re traditionally introduced to the protagonist’s world at an absurdly opportune time and characterized by an amazing ability to producing get characters where they need to be. On screen, the fabric of spacetime bends toward resolution. In reality, less so.

Real wormholes are a theorized explanation for the movement of matter that have real potential to make interstellar travel possible — albeit in a very complicated, unfilmable way.

Wormholes are basically a spacetime feature that connects two separate points. Those points could be lightyears apart or just a few feet from one-another; they could exist in different universes, or even in different points in time. Regardless, a wormhole connects them. Think of it as a tunnel that basically runs between two places and physically shortens the distance needed to travel between them — be it a physical distance or time itself.

In Einstein’s theory of general relativity, a common wormhole is actually distinct from a traversable wormhole. The latter can only exist if an exotic type of matter that possessed a negative energy density could stabilize the structure and keep it from collapsing. According to the astrophysicist Kip Thorne, number seven on our astronomy power rankings, a stable wormhole would probably hold itself together through a shell made of dark matter — which has never been found but is pretty much assumed by scientists to make up 84.5 percent of the total matter of the universe.

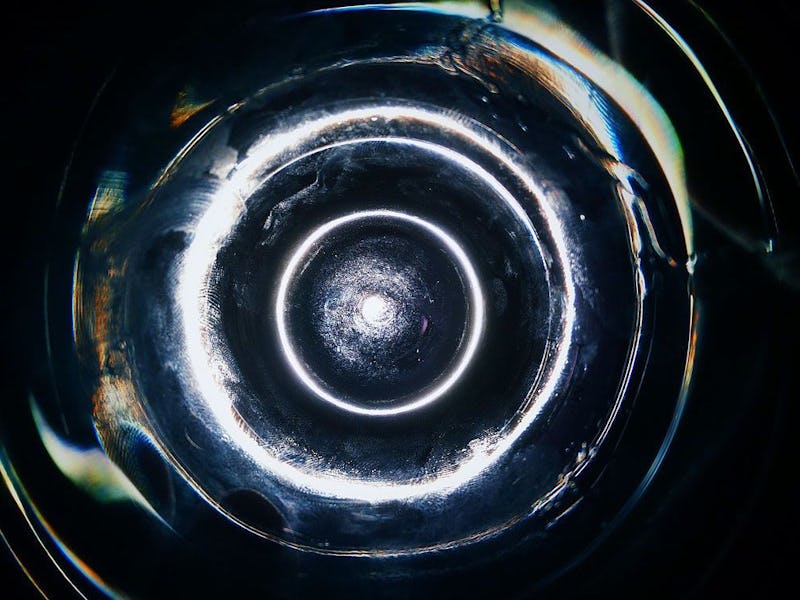

A diagram of what a wormhole might look like.

So why exactly does any of this (no pun intended) matter?

Nearly all work that goes into space exploration these days is focused around a larger goal of finding other planets and moons in this galaxy or the next that are habitable. And the only way to find out is to actually send robots or even humans over and investigate. Unfortunately, interstellar travel is extremely difficult. We’re nowhere close to sending humans beyond the solar system. Hell, we can’t even get astronauts to Mars yet. And we’ve only sent one probe into interstellar space so far: Voyager 1. It took 35 years to get there.

If we want to explore other parts of the universe, we need to either develop better spacecraft propulsion technologies, or find shortcuts. There are perhaps a few propulsion technologies that could work, but it’s totally unclear how long they’ll take to develop. And as with any powerful technology, we’ll need massive amounts of resources to run those things — and who knows whether those materials will still exist in the future.

So we have to turn to shortcuts. As crummy as Interstellar was, it still illustrated how a wormhole might provide safe passage to other worlds light-years away from Earth. There’s no question the movie takes liberties, cutting out the strange, potentially violent activity that might complement a literal rip in spacetime. And yet, if a wormhole could take us to places far beyond our own star system, it could do wonders in helping humans bypass the need to develop insane technology that would make light-speed travel possible. Warp speed may, in fact, simply be a method of creating a miniature wormhole and shipping a spacecraft through it to the other side of the universe.

There are also other kinds of travel that a wormhole might make possible. One is time travel. (Here’s where you ignore Interstellar and think about Star Trek.) The idea is that one end of the wormhole could be accelerated to a higher velocity than the other, creating a relativistic time dilation in which time moves more slowly at the accelerated end than at the normal end. An object entering the accelerated end would therefore exit the normal end at a time prior to its entry (i.e. go back in time). The physics are bit more complicated and nuanced than that, but you get the point — a wormhole might actually make traveling back in time work. No kind of warp drive technology could make that possible.

The other potential feature of a wormhole has to with traveling between different universes. Many physicists and cosmologists agree that we live in just one of many possible universes. There’s still no proof of this, but one wormhole-related theory suggests these spacetime tunnels could be used to connect different universes. In fact, this idea argues that a particle that uses a wormhole to travel back in time doesn’t actually travel back in time at all: It simply goes to a parallel universe.

Before we can pursue these possibilities, we need to do two things: Finding a wormhole and figure out how to keep it open. When we do that, the science fiction of the past may pale in comparison to the options of the present.