Can Using the Silk Road Get You Arrested?

The "mentor" to the Silk Road's founder was just arrested in Thailand.

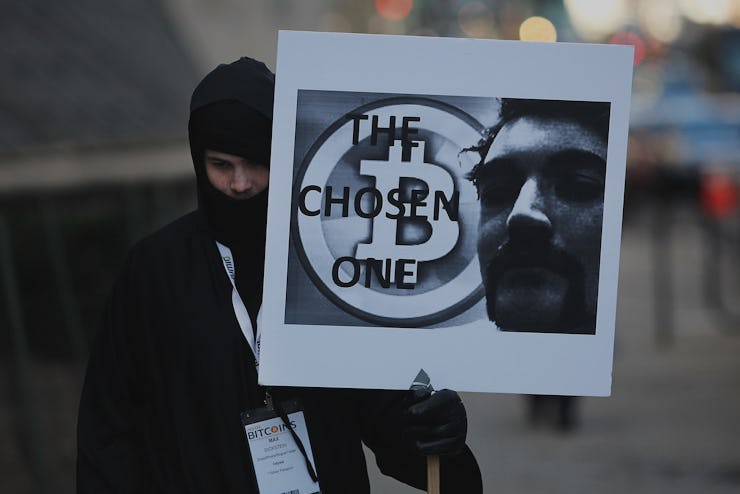

Recently, one of the major players behind the defunct black market Silk Road was arrested by the FBI. Roger Thomas Clark was arrested in Thailand and charged with one count of narcotics conspiracy and another count of money laundering conspiracy; the former carries a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years. Clark’s arrest follows a judge’s May decision that handed Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht a life in prison.

With another online drug kingpin — Clark is described as Ulbricht’s “mentor” — facing time behind bars, it seems less enticing than ever to buy illegal products off the internet. If they could get caught, couldn’t anyone?

There’s no risk in using Silk Road, in particular, because it’s long gone. There have been a number of offshoot sites, however, that are colloquially called “the Silk Road.” (It’s like asking for a Kleenex when you know that box says Puffs right on it.) Still, many of those sites have been shut down, as well. Silk Road 2.0, for example, shot up very quickly in 2013 in the original’s absence, but just as quickly, its founders were arrested.

But what about those who aren’t directly involved in the platform’s creation? Back in 2013, following Ulbricht’s arrest, several sellers around the world were arrested. Among them was Steven Lloyd Sadler, who was considered among the “top one percent of sellers.” Earlier this year, he was sentenced to just five years in prison. In 2014, another 17 people were arrested globally for online black market involvement.

With many arrests and several websites shut down, one of the remaining major marketplaces is Agora. Even Agora, though, took itself offline earlier this summer — presumably temporarily — as a precautionary measure. While it functioned, Agora-related arrests were sporadic but not infrequent. In August, for example, three men were arrested in Bangalore, India for peddling drugs that they obtained from Agora. The drug dealing was a crime in and of itself, but it’s notable that the men fessed up to where they got the contraband from.

More prominently, United States and Australian investigators arrested many customers who purchased firearms on Agora. Additionally, five people were arrested in October, along with two million pills (among them, knockoff Xanax bars) and $200,000 in cash, in Canada. And, in a more amusing case, a Swiss robot got arrested for buying a number of products on Agora. It was for an art project that tested the reliability of the deep web, arming a robot with $100 in Bitcoin and letting it run wild.

Other than the robot (which bought a Hungarian passport, likely from an extra shady dealer and thus triggering authorities) and the three men in Bangalore (who were just normal drug dealers), most of those who’ve been prosecuted were prominent users of deep web marketplaces. It’s not safe to buy illicit products online, but it’s a deliberately illegal activity to begin with. There’s obviously risk involved. But if you’re not hoarding a third-of-a-ton of narcotics — like a German man who was arrested in March — or a campus dealer with 809 Xanax pills who was bound to get caught regardless of where the product came from, and you’re also not someone buying weapons, it’s not like the government is watching your every move.

That’s not to say that you should use deep web marketplaces. It’s incredibly dicey to have any identity trace connected to illegal dealings. Still, the recent wave of Silk Road and other arrests, only shows that the government is working on a top-down approach. Simply using the deep web to buy recreational drugs will not get the feds on your tail.