How the Founder of the North Face Spent His Fortune Preserving Chile's Wilderness

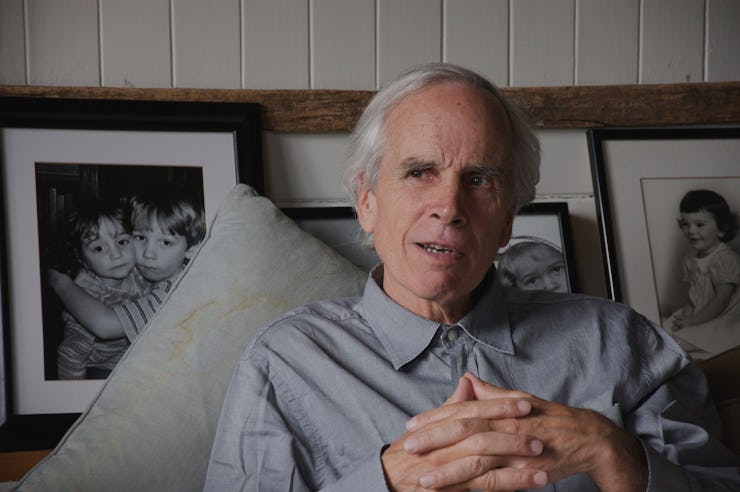

Douglas Tompkins died in a kayaking accident this week. His legacy is a dozen South American wilderness parks.

It was probably Douglas Tompkins’s love of the wilderness that made him so good at his job running the outdoor gear empire The North Face and clothing company Esprit. A businessman is what he was for a brief time, but he lived and died a naturalist.

Tompkins died Tuesday in a kayaking accident in Chile after his boat overturned in rough waters, exposing him to severe hypothermia. His was flown to a nearby hospital, but did not survive. He was 72.

Esprit sold in 1990, and Tompkins’s stake was reported at more than $150 million. The VF Corporation later scooped up The North Face, which had been struggling financially, for $25 million.

But Tompkins was already gone. He moved to South America after the Esprit sale to concentrate his efforts on conservation. How would he do it? Use his millions to buy up large parcels of land that would be protected as nature parks, and eventually handed over to a national conservation organization.

This is Pumalin Park in Chile, one of the nature preserves saved by Douglas Tompkins.

At one point, the Chilean government stepped in and purchased a piece of land that Tompkins had been eyeing, to avoid the political backlash.

“We want to do something good, but you’ve got to be very naïve and out to lunch to think that certain sectors of society are not going to put up resistance,” he once told the New York Times. “If you’re not willing to take the political heat, then you shouldn’t get into the game of land conservation, especially on a large scale.”

Pumalin Park covers 1,250 square miles of Chile's Patagonia region.

Selling the idea of foreign funding for parks creation to presidents and governments wasn’t all that hard, Tompkins has said.

“Here’s a private foundation giving large chunks of land to the national patrimony. The government and the president — that part is not difficult. It’s getting through the labyrinth of ministers and officials below them. You have to really sow the idea and show that it is a good idea.”

The hardest part is combatting land interests at the local level, he said. “The simple reason is that the locals have a vested economic interest right there where conservation is being proposed. They do not want anyone telling them that they are diminishing or degrading their very own place, and they don’t want anyone else putting their hands in the cookie jar that they have their own arms into up to the shoulder.”

It sounds kind of harsh — coming into a place and telling the locals that they can no longer use the land in the way they have to their own economic benefit. But if you’re fighting a war to protect pieces of relatively untouched wilderness from encroaching devastation, there’s only so much room for sentimentality.

In some ways, Tompkin’s intrusion on the Chilean government is not so different from that of a multinational mining company — both use their economic and political sway to gain exclusive access (for a time) to a piece of land.

The end game, though, is different. A mining operation offers a local economy for as long as the mine operates, but also comes with the risk of deaths and environmental catastrophes. Best-case scenario, at the end of the day the people of Chile are left with a well-contained mess.

When naturalists like Tompkins buy land to preserve it, it creates a potential local tourism economy in perpetuity. At the end of the day, the land reverts back into government control, to serve the best interests of future generations of Chilean people.