You May Actually Want to Opt in to the Facial Recognition Tech of Tomorrow

FST Biometrics scans your body language as well as your face for a smooth, simple form of ID. But its implications could be more invasive.

The convention floor of the Javits Center in Midtown Manhattan is filled with every type of security camera and surveillance software vendor from across the world. I’m walking away from the Supaquad display – where the sales rep showed off his drone-plus-camera hybrid – when somebody tries to get my attention.

“Hey, I met you here two years ago,” says one of the sales reps at the booth for FST Biometrics, an Israeli bio-identification company. Beyond the immediate weirdness of being identified by someone who works in facial recognition software, it occurs to me that I might not be as anonymous as I thought at this surveillance bonanza.

FST Biometrics is one of hundreds of vendors here for ISC East, a two-day event that bills itself as the largest physical surveillance show on the East Coast. Most of the eye-grabbing displays here are for internet-connected smart cameras, but sometimes you get a company slightly more afield. For instance, there’s the social media monitoring site Geofeedia, whose product vacuums up geo-located tweets for cops and corporate executives.

I’m scheduled to interview someone from FST later, but I figure why not take a minute to reconnect with my old friend. It turns out his name is Brian Fishler, sales manager, and I ask him what’s changed at FST lately. First, he gives me the general sales pitch.

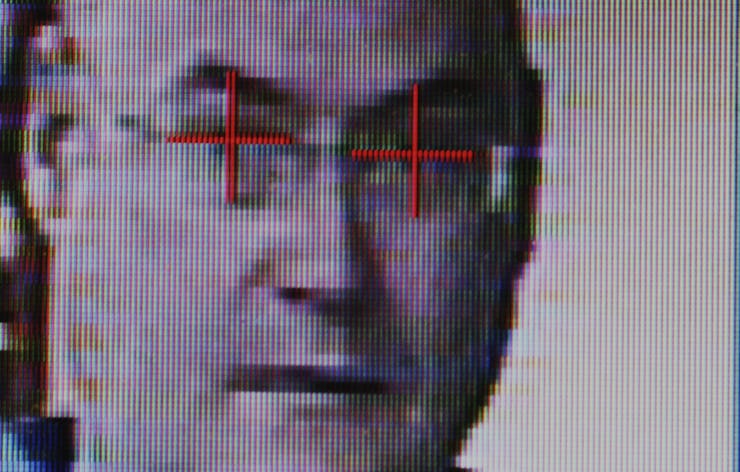

The company’s specialty, from its founding, has been to incorporate behavioral identifiers with facial recognition capabilities. In plain English, that means that as someone crosses the lobby of a large office building, a camera captures not only their face, but also their gait, body size, and shape. If the product works properly, the person doesn’t have to stop at a security gate and swipe a badge – the doors simply open for him, and he walks on through without breaking stride.

Facial recognition tech is popular in movies, dating back to at least Enemy of the State. Recently, Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol had a memorable scene where one character puts in contact lenses and scans a crowd until he identifies his mark. We’re not there yet, but FST does have a video that purports to show a Google-Glass-like device ID-ing people as they walk around. I haven’t seen it demo-ed, and promotional videos are notoriously unreliable, but the tech is evolving fast.

So what’s new at FST? “You can connect to your whole database on a smartphone now,” Fishler says. So if you’re a security guard – or a concerned staffer – you can scan a person’s face with your Android phone and if they’re “enrolled” in the program their information will pop right up.

The other new feature is what the company calls a feedback tablet. It was hard to get people to look right at the camera as they approached it, but if you mount a screen underneath that shows what the camera sees, Fishler says a lot of people will check themselves out as they pass by. “It was the financial institutions,” he says. Apparently the bankers “wanted to look at themselves.”

Later in the day I interview Arie Melamed Yekel, FST’s chief marketing officer. Unlike many of the vendors here, Yekel doesn’t make an explicit pitch to law enforcement. “We’re not looking for bad people,” he says. “We’re looking for people who want to cooperate with the technology and work to get that convenience of being identified without changing their behavior.”

But as with all the seemingly value-free surveillance devices at this conference, the political subtext for their possible use is never far away. FST’s founder, Major General Aharon Zeevi Farkash, was the head of Israeli intelligence when he retired from the Army. “During [Farkash’s] service he came across the Gaza checkpoints, and he saw tens of thousands of Palestinians were standing in a queue,” Yekel says. “They stood in a queue for two, three hours just to cross. And they were all innocent people, people who want to go to work. His thought was we’re looking for one, two, three terrorists, but we’re creating so many enemies. There are 30,000 people just standing here.”

The idea was that if you could faciliate quicker, less intrusive security measures, Yekel says “we could eliminate, or at least reduce, the number of enemies we’re making every day.”

It’s a story FST has told the press before, and seems to be central to the image the company wants to project. Whatever the political implications would be for implementing a massive digital surveillance database in Israel and Palestine will have to wait. As of now, FST doesn’t operate in any Palestinian territory.

The story brings up important issues though. For now, the technology is easy to defeat, Yekel says, offering to show me how not to be ID’ed. It is, after all, for people who want to cooperate. But what about the privacy considerations for people who are coerced into cooperating? What about people who are cooperating without a full understanding of the implications? How long before the drone-plus-camera I saw at the beginning of the convention can successfully run the FST mobile app?

Another promo video on the FST website shows how the software could allow a store manager to recognize a regular shopper, and to give her the VIP treatment. If this type of technology goes viral, will stores sell their customers’ biometrics ID databases to the highest bidder, the same way they sell all kinds of consumer information now?

We are moving into the age of the Internet of Things, where every device talks with every other device. Maybe we are also moving into the age of the Database of Bodies.

When I get home I google Fishler, and it turns out he joined FST in 2014, so it’s impossible that we met two years ago. Could have been last year. The human mind is imperfect.

Maybe next time we’ll be able to ask his software.