Apollo 11 Was Seconds Away From Having to Abort the Moon Landing

Few people know quite how close the Eagle came to never landing on the lunar surface.

History has demonstrated that the space race of the 1960s was the first endeavor of man, other than war, to challenge our entire scope of scientific and technological capabilities. The crowning moment in this challenge was when Apollo 11 traveled 260,000 miles into space, landed two astronauts on the moon, and returned safely — a momentous event that took place 50 years ago this month.

However, the full scope of scientific and technological capabilities at that time was not as advanced as many might think. It’s not until a few truths are revealed that it becomes clear how many seemingly impossible problems were overcome with little more than daring and determination.

"Mission control received tracking data that indicated it was not on the proper trajectory.

Despite filling a whole room of the building, compared to modern computers of today, the total processing power of the computers in mission control was minute and had no more power than one of today’s laptops.

However, running a space mission on the capacity of a single, modern laptop was luxury compared to the computer power on the spacecraft itself. This was comparable to something between a digital watch and an early mobile phone.

As Apollo flew to the moon, hundreds of communications bounced between the spaceship and ground control. Failing to comprehend just one message could spell disaster. This placed everyone, from the most junior team member to the flight director himself, under immense stress.

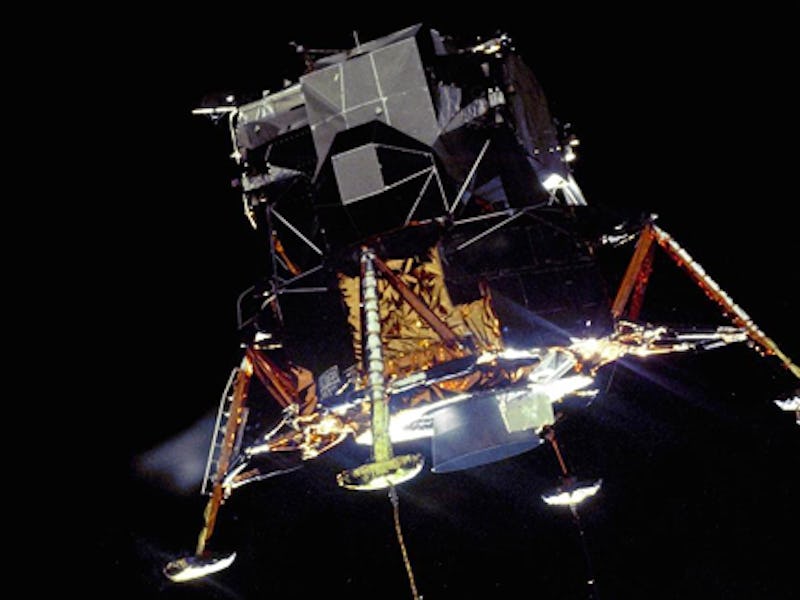

Neil Armstrong inside the lunar module, Eagle.

As the craft reached lunar orbit, the astronauts prepared for what would be the most dangerous and unpredictable part of the mission: the descent to the moon itself. But as soon as the spacecraft came around from behind the dark side of the moon, mission control received tracking data that indicated it was not on the proper trajectory.

Flight Controller Steve Bales called out, “Flight, I’m about halfway to my abort limit here — we seem to be out on our radial velocity.”

As soon as he said the words “halfway to my abort limit,” all contact was broken with the lunar module. Mission control could no longer talk to the astronauts.

Without communications or computer data, no one at NASA could monitor the module’s systems or control its decent. Desperately, they tried another way. They re-routed a link to the lunar module via Mike Collins in the orbiting command ship. This patched-up improvisation restored a weak signal between the crew and the ground — but it wasn’t to last.

It was up to one man, Flight Director Gene Kranz, to decide if mission control had enough information to make the “go/no go” decision and continue the decent to the moon. Five minutes prior to powered descent, he had his controllers go through a “go/no go” and, immediately, they lost data again. So, he added the words, “Give me your ‘go/no go’ based on the last valid frame of data that you saw.”

Flight Director (Kranz): “OK, all flight controllers, ‘go/no go’ for landing.”

Retro [Retrofire]: “Go.”

Fido [Flight Dynamics]: “Go.”

Guidance [Navigation]: “Go.”

Control [Control for the LM]: “Go.”

INCO [Integrated Communications]: “Go.”

GNC [Guidance, Navigation, Control]: “Go.”

EECOM [Electrical, Environmental, and Consumables Manager]: “Go.”

Surgeon [medical]: “Go.”

CAPCOM [Capsule Communicator]: “We’re go for landing.”

So, as communications cut in and out, the lunar module began to power its way down to the surface.

This descent was more like a controlled fall out of orbit, comparable to a car on a very long mountain road with the driver riding the brake to adjust the speed, keeping it from going too fast.

Buzz Aldrin in the lunar module.

To avoid colliding with the moon, the lunar module now switched on its landing radar to determine its precise altitude. However, switching on the landing radar started a near-catastrophic chain of events that would turn the landing from a dilemma into a nail-biting drama.

An alarm sounded in the lunar module. Commander Neil Armstrong called out, “It’s a 1202…”

Mission control responded, “Stand by … 1202.”

No one knew what the alarm meant. Overwhelmed by information from the landing radar, the tiny, on-board computer had crashed. Instead of giving the crew vital information, it was flashing up a major overload warning. On board the lunar module, the astronauts were aghast.

"We got a bunch of guys here about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot."

However, Jack Garman, an Apollo 11 computer engineer, had come across this alarm in a training exercise — go deep on the 1202 alarm with this explainer in Discover magazine — and had scribbled down the correct course of action on a scrap of paper. He advised that if the alarm was a one-off, the mission could continue. But the problem didn’t go away. The landing radar continued to overload the computer.

Mission control: “We’ve got another 1202 alarm.”

With the computer plunging the lunar module into chaos, Armstrong decided to override it and take manual control of the vehicle. But by now, the spacecraft had veered a long way off course.

Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin were now flying over landmarks they didn’t recognize — the lunar module was lost. That wasn’t all; the descent engine’s fuel tank was running critically low. With the module still at 500 feet, it was rushing into unknown terrain.

Neither the astronauts nor the mission controllers had ever expected or rehearsed such a white-knuckle scenario. They started a clock to count down how much fuel was left.

(L-R) Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin — the crew of Apollo 11

Kranz instructs his controllers, “OK, the only callouts from now on will be fuel…”

Armstrong knew the fuel supply was dwindling; he had to find a safe spot to land. Looking out of the window, he saw a large crater littered with boulders the size of small cars, which is where the computer was taking him. With the fuel rapidly running out, the astronauts were faced with a serious problem.

Normally, the easiest option is to slow the rate of decent and simply fly over any potential obstacles, but this would take more time and burn more fuel, reducing the remaining fuel required for takeoff.

Then, mission control in Houston gave this message: “Sixty seconds.”

Anyone who has seen and heard the NASA footage replayed can assume with little or no thought that this is simply a calm call from mission control indicating how much time is left before the Eagle touches down. This was not the case.

Aldrin had to be careful not to disturb Armstrong’s concentration, but at the same time, he was anxious to get the lunar module on the ground as soon as possible.

Charlie Duke manned the CapCom desk during the Apollo 11 mission and was later lunar module pilot on Apollo 16.

Their spacecraft continued to skim over the dusty, gray lunar surface.

The call went out from Houston: “Thirty seconds.”

Anyone at mission control not already on their feet now stood up as the tension continued to rise.

When simulating all possible outcomes while attempting to land, NASA had concluded that if it ever came down to 30 seconds, they would scrap it and abort the mission. But Armstrong could see the surface of the moon through his small window, and he knew that if he just kept going a little longer, he would land the lunar module safely.

Through the windows of the lunar module, Aldrin could see the shadow of the spacecraft getting bigger and bigger, and dust began picking up around them. Over the radio, he informed mission control, “Contact light. OK, engine stop…”

Armstrong confirmed they had indeed touched down: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Houston heaved a collective sigh of relief and responded, “Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. We got a bunch of guys here about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

As everyone at mission control caught their breath, they looked at their stopwatches … Apollo 11 had landed with 15 seconds of fuel to spare.

The 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing is Saturday, July 20, 2019.