RETRO GAME REPLAY | 'Donkey Kong' (1981)

Man versus beast became man versus man. Adam Sandler can't ruin this.

So, Pixels is a mess. The Adam Sandler “comedy” has been the victim of vitriol with anyone with eyesight, comprehension, and a functioning cortex.

Nintendo’s involvement in the film is curious. The company safeguards its toys, lessons learned from when it lent The Legend of Zelda and Super Mario to Philips for its CD-i and Philips created hot garbage. But after Disney’s excellent Wreck-It Ralph, they thought it’d be okay to give Adam Sandler Donkey Kong.

Shame on them, because they’ve been fooled twice.

But Adam Sandler alone isn’t powerful enough to destroy a gaming icon. It helped create a gaming empire. It coined the challenge phrase for the ages that has since become its ethos, you versus me, and the subject of a compelling documentary about grown men fighting one another for bragging rights: This is Donkey Kong.

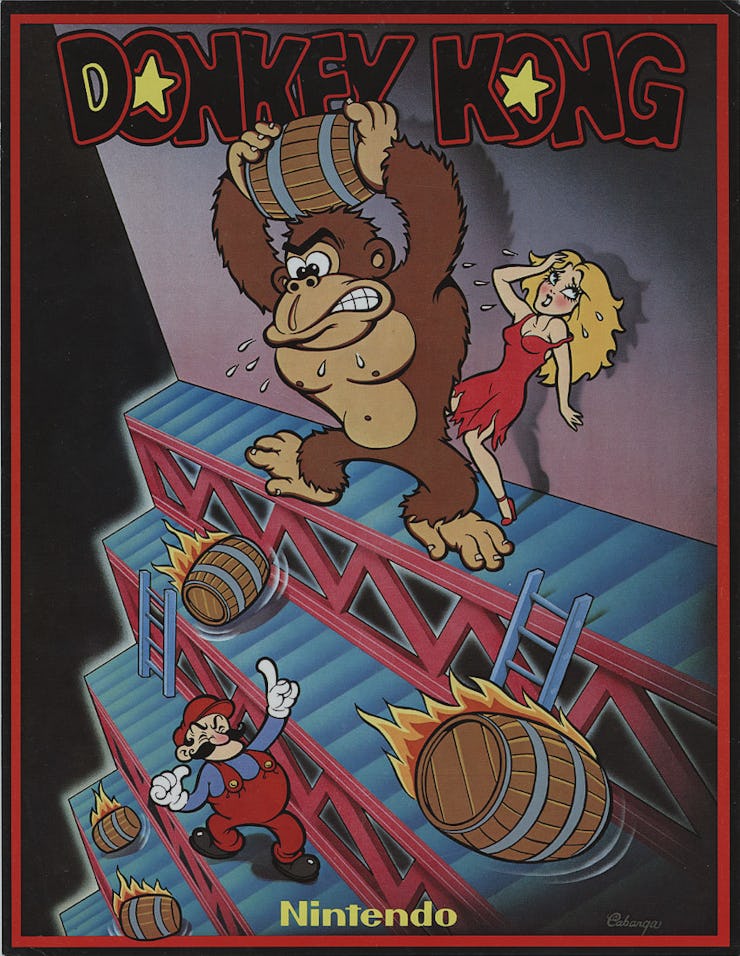

The premise is simple: As Mario, who possesses the inhuman ability to jump, you must rescue Paulina, who is decidedly not a princess, from the clutches of Donkey Kong, who is decidedly not a donkey. Climb ladders, jump barrels, dodge fire, go for glory.

It’s man versus wild in a challenge of timing, precision, and pure wit.

For all the foundations it laid for gaming and popular culture, its premise is remarkably aped (pun intended) from old Hollywood. Had director Shigeru Miyamoto existed decades before, Donkey Kong could have been a Ray Harryhausen movie.

Donkey Kong is loaded with history in its creation and its impact decades later. So to sharpen your bar trivia, take note of how Nintendo’s creativity was born out of technological necessity and not acid binges.

Why the hell is an ape named Donkey Kong? According to credible legend, you can blame it on a Japanese-English dictionary: Miyamoto wanted to name the game after its strongest character, and wanted to convey that the ape was a stupid, stubborn, bumbling mass of beast. He found the word “donkey” to mean “stubborn,” and went along with it obliviously.

Mario, originally “Jumpman,” was created for the game with the overalls, mustache, and hat because it was necessary. Miyamoto couldn’t code hair or faces. Without the overalls, Mario would have looked like a round cluster of pixels. All of his signatures allows you to read him as “A Decent Representation of Some Kind of Human Being” in 8-bits.

Why “Mario”? An argument. Mario Segale was Nintendo of America’s warehouse landlord when the company was still a scrappy upstart expanding to the West. After a heated argument over rent with Nintendo’s president Minoru Arakawa, the team decided to name their plucky hero after the guy that wanted their money. That I have no explanation for. In a 2010 interview, Segale marked, “You might say I’m still waiting for my royalty checks.”

The chase for the world’s highest score has been well-documented. The 2007 documentary The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters followed the dethroning of record holder and hot sauce entrepreneur (Totally real) Billy Mitchell from Steve Wiebe, a mild-mannered high school teacher. Director Seth Gordon said Billy was a “true puppet master” and “master of information-control.”

The story doesn’t end there: A new generation of Kong players have since etched their names in the pantheon, including plastic surgeon Hank Chien and cartoon French-Canadian Vincent Lemay. Truly, Donkey Kong’s fostering of human grudges is everlasting.

But in the end, Donkey Kong was and is a game, exceedingly simple in its gameplay and complicated in its impact. Rivalries, friendships, memories, all born of one distraction you can still play in a trendy bar in Brooklyn somewhere over thirty years after its time.