Scientists Figured Out How to Use London's Huge Fatbergs for Good

Who says a rock-solid grease clot has to be a bad thing?

London’s infamous fatbergs are rock-hard, stadium-length clots of congealed fat, wet wipes, and soiled diapers. They’re also a potential fuel bonanza. While London’s waste management teams have been hard at work hacking at the fatbergs with shovels, a team of scientists at the University of British Columbia has been trying to figure out how to turn the UK’s fat-clogged lemons into greasy, functional lemonade. In a new study, they report they’ve discovered the recipe.

The new Water, Air, & Soil Pollution paper shows how future Fatty McFatbergs (that’s what Brits named the biggest one) can be used to churn out methane — a “clean” fuel that, when burned, releases water and low amounts of carbon dioxide relative to fossil fuels. Among the many biofuels that can be made from organic waste like fatbergs, methane is a particularly practical option for large-scale production.

“Anaerobic digestion systems commonly exist in municipal sewage treatment plants,” study co-author and research associate Asha Srinivasan, Ph.D. tells Inverse. “So, it would be advantageous to make use of the existing infrastructure to produce methane.”

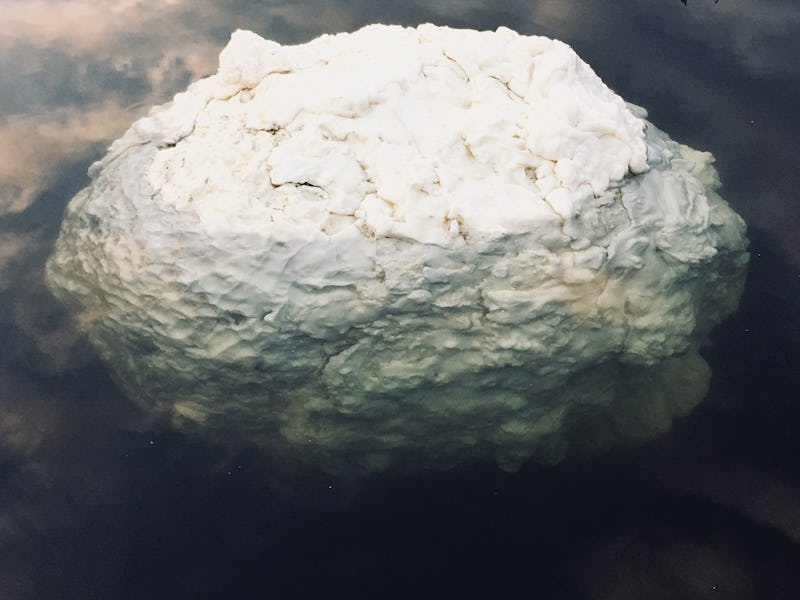

A model of one of London's fatbergs, showing its size compared to humans.

The greatest obstacle that scientists have run into when trying to make fatbergs useful is that they must first be broken down into useable parts, which isn’t easy to do. “In a bio-digester, microorganisms find it difficult to breakdown FOG,” Srinivasan says, referring to “fats, oils, and grease,” which comprise fatbergs. “Our process helps to breaking down FOG making it easy for the bacteria to digest and produce more methane.”

Molecularly speaking, the fats, oils and grease — or FOGs — that make up fatbergs are energy gold mines. But to be turned into fuel, they need to be broken down into components that bacteria, which are integral to the fuel-production process, can munch on. Fatbergs tend to contain antimicrobial compounds (all those hand soaps, perhaps) that have traditionally made this process difficult, and usually the FOGs have to be pretreated with other chemicals. It’s not the most efficient process, which is what we need, as fatbergs become more and more plentiful.

The new process blasts the solids out of raw fatbergs, turning them into liquids that bacteria can more easily break down into methane.

In the new study, the team figured out that blasting FOGs with microwaves and adding hydrogen peroxide to the chunks can help. Using their new process, the team was able to decrease the number of unusable solids in the FOG samples by up to 80 percent and release more fatty acids, which can be further broken down by bacteria to make fuel. The technique will prove to be even more useful as engineers figure out how to remove the unusable solid bits from sewage before they find their way into solid fatbergs.

“Effective source separation techniques like grease traps at the source can help to divert FOG from being discharged into the sewer lines,” says Srinivasan.

Part of London's fatberg is on display at the Museum of London.

The new process is in the pilot scale testing stage, and demonstration tests are underway at municipal sewage treatment plants and dairy farms. “A full-scale system is expected to be in place in a year or two for these applications,” says Srinivasan.

Soon after the fatbergs were first discovered lurking in the sewers of West London in 2017, scientists with Thames Water, the private utility company that deals with the city’s water supply, suggested they could turn the biggest fatberg — all 850 feet and 143 tons of it — into 10,000 liters (about 2,640 liquid gallons) of biodiesel. As this new process is refined, it’s possible they could eke out even more, turning the worst kind of trash into a very useful kind of treasure.