The Cynicism and Hope of Mister Rogers and 'Won't You Be My Neighbor?'

It took me a week to see the light in 'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.'

To put it simply, things are bad now. There’s no need to recount the ways in which life feels like it’s crumbling around us, but by the time I made it to the press screening of Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, I had already had multiple conversations that day about Donald Trump, journalism’s slow decline, twentysomething ennui, that sinking feeling that you’re just old enough where you might not be able to make the drastic change you need to be happy. At least I could look forward to the 94 minutes in which I’d be swept up in the imagination of childhood hero Fred Rogers.

The new documentary, now in theaters, follows the life and legacy Rogers built, eking out scraps of humility, empathy, and acceptance that audiences have quite honestly forgotten that they can feel. The film left me glowing, hopeful — until I stepped into a bar with some colleagues who also attended the screening and we quickly sunk back into the ever pressing realities of 2018.

Outside of the comfort of the neighborhood, cynicism returned, and I saw another side of Mister Rogers. Throughout the documentary (and his career), he was doing more than just putting on his cardigan and comfy house shoes. He also pushed an immense boulder up a hill, only for it to tumble down the other side. Mister Rogers was Sisyphus.

How quickly I’d let the good feelings I’d gotten from Won’t You Be My Neighbor? curdle made me question how effective it — and Mister Rogers — was. There’s a recurring theme in the documentary. Mister Rogers went into television in the first place because, just as he was about to enter the seminary, he saw a man smash a pie into another man’s face on a kiddie TV show. Children deserved better than that, Rogers decided. They deserved Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, directed by Morgan Neville, makes a compelling case for why Rogers was right, and why his show was good for kids. Not only did Rogers open the eyes of children to the trials and tribulations of those who were different than they were, he saved PBS, essentially making it possible for kind, educational children’s television to exist as we know it.

Daniel Tiger and Mister Rogers.

Still, that lowbrow, toxic TV that Rogers opposed never went away. The documentary keeps invoking the specters of Pee-wee’s Playhouse, Superman, and Transformers as action-packed televised sludge that caught young eyes despite Rogers’ intentions. Rogers could only do so much, and Won’t You Be My Neighbor makes a point of showing how the hurtful aspects of pop culture continued to thrive even as Rogers stood against them. This subtle presentation of Rogers’ limitations is made more upsetting when you remember just what sorts of acute traumas Rogers would have to respond to in 2018. If Rogers really was the irrepressible embodiment of good we all remember him to be, would we be breaking up desperate families at border walls, losing ground to white supremacists, or suffering an epidemic of school shootings?

The shot in the movie that’s still lingering in my mind comes towards the end. It’s footage of Rogers, standing alone and looking into gusting winds atop a hill on a grassy beach. He’s holding firm against the wind and melancholic, overcast sky, but the wind isn’t stopping. In a voiceover, his wife Joanne Rogers questions what her late husband would do if he were still alive in these especially trying, not-very-nice times. Maybe he’d give up, she posits, briefly.

The unsettling admission that even a man who never gave up has his limits points to the hidden truth of Won’t You Be My Neighbor?: Rogers is human, a person who made a difference but was never capable of curing all ills despite what our rose-colored memories might insist. If you’re looking for absolution and a sense that everything will be okay in the end, the limits of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood as outlined in the documentary won’t allow that. That makes it a good documentary, instead of pure hagiography, but it wasn’t the balm for the soul I needed.

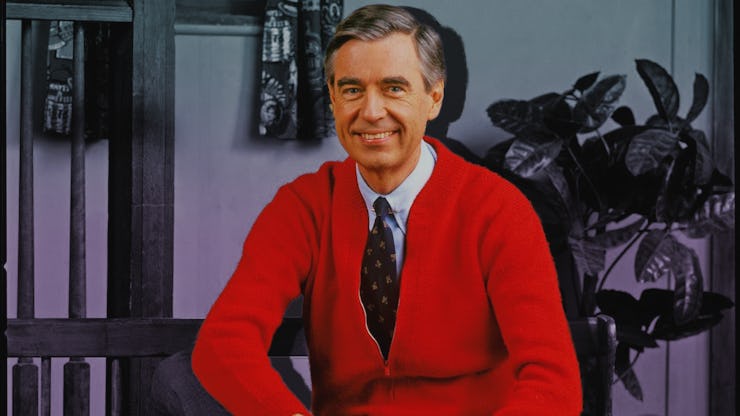

Fred Rogers.

Rogers’ ethos was that children have feelings and fears just like adults do, which was why his show was so kind and straightforward. Kids should be given more credit and more support, and Rogers knew that. Adults have their own problems too. Not every crummy circumstance can be changed with a visit to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, and depression can’t be permanently fixed with soothing words from a TV show host. Won’t You Be My Neighbor was never going to make everything okay, the way we remember thinking it might be when we were kids. Not even Mister Rogers could do that.

I grappled with this unwanted cynical view of Won’t You Be My Neighbor? while procrastinating putting it into words for a review. I liked the movie, I felt good and wept while watching it, but then it ended, and in the context of the real world, the neighborhood seemed smaller than I’d like.

Last week was hard. The deaths by suicide of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain were shocking and tragic; the loss of two beloved figures seemingly more bad news, more reason to throw your hands up. In this darkness, though, was a light in the most unexpected place imaginable: Twitter. For the first time in as long as I can remember, my timeline was almost entirely affirming and supportive, the normal flow of fatally ironic memes and verified Nazis replaced by love. People were talking about what Anthony Bourdain meant to them, celebrating him for the way he celebrated cultures other than his own. People were tweeting messages of support, recounting their own struggles with depression and offering lifeline after lifeline to anybody who might be reading. People were trying to help one another, and seeing this outpouring was what I needed to find the truth that was always in Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

The film doesn’t end with a grand statement about how Mister Rogers changed the world. It doesn’t even really end with a statement about how Mister Rogers, specifically, changed anything. Instead, it looks to the last commencement address Rogers ever gave, at Dartmouth College in 2002.

“I’d like to give you all an invisible gift,” Rogers tells the soon-to-be graduates in his endlessly calming voice. “A gift of a silent minute to think about those who have helped you become who you are today.”

“Whomever you’ve been thinking about, imagine how grateful they must be, that during your silent times, you remember how important they are to you,” he continues. “It’s not the honors and the prizes, and the fancy outsides of life which ultimately nourish our souls. It’s the knowing that we can be trusted.”

Every one of the people interviewed for the documentary is given, on camera, sixty seconds to think about people who helped them. We don’t hear all their answers, but it’s clear from their faces how warming this love is, how receiving help gives purpose to both people involved.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? honors a man who meant so much to so many people, but its greatest triumph — its true message — is that Rogers would’ve thought that you matter. Moreover, it’s that somebody thinks you matter, and to help and to have faith in a person makes all the difference in their world. Mister Rogers was not the only good person out there, and he wasn’t the sole arbiter of kindness and validation. We all are, Rogers was just especially good at making sure everybody knew how much they meant.

It was there in the title, all along. It’s, as Rogers puts it, “an invitation.” The neighborhood, that warm place where things make sense and there’s always somebody to help guide you, still exists because there are people in it.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is now in theaters.