Fact-Checking Neil Young's 'Monsanto Years'

The Canadian zen master has a heart of gold, but lacks the mind of a scientist.

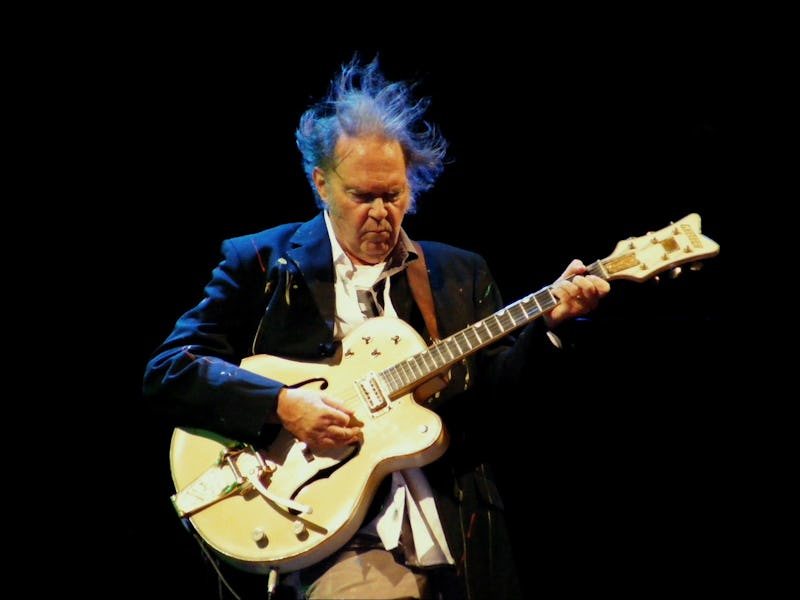

Neil Young, one of the most prolific musicians of the modern era, has just put out a new album attacking big corporations, unregulated capitalism, and sprawling corruption in all levels of the government. This would be shocking behavior if Steven Tyler did it, but Young’s work has always been political. Still, The Monsanto Years is a more specific attack, an attempt to go for the genetically modified jugular that spills little blood. The album has some lovely songs and some terrible reasoning.

Monsanto Years finds Young in familiar musical territory, but his are thick with the kinds of claims popular in anti-GMO circles. If Young’s traditional political opponents — or straw men — have been slow to embrace scientific consensus (coughclimatechangecough), his allies may have been overeager to believe the worst. Young, smart as he is, falls for both false ideas and ginned up conspiracies. Here are a few of the more egregious lyrics assessed as public service announcements, not music.

Don’t say pesticides are causing autistic children — “People Want To Hear About Love”

Reported cases of autism have gone up dramatically since the 1980s, from less than 1 to 14.7 diagnoses per 1,000 children. The reasons for this aren’t clear because the causes of autism are not known. Theories range from uncontrolled genetics to environmental factors like pollution and exposure to chemicals. Rates may have also gone up simply because physicians are better at diagnosing autism now than ever before. Most scientists will tell you the trend is likely a product of all three factors.

Young’s caustic lyric is probably referring to several studies — most notably this one from last October conducted by researchers at the University of California, Davis — that have come out in the past decade claiming to have found a correlation between pesticides and autis. In that critical study, epidemiologist Janie Shelton and her colleagues observed 970 children born in farming areas in Northern California and claimed to have found that children living less than a mile from pesticide were 60 percent more likely to have autism.

But it’s wrong to make this kind of conclusion based on the nature of this study. The 970 sample size is not large at all. As an observational study, it’s difficult to assess how much pesticide the children were exposed to: Simply living next to a farm field in California doesn’t really mean anything. Most of all, neither this study nor any other can point to why pesticides would cause autism. Chemical exposure is probably not a good thing in any situation, but there’s no reason to think autism is directly related pesticide use.

Young, it turns out, is giving good advice sarcastically: Don’t say pesticides are causing autism because we don’t know that.

If you don’t like to rock Starbucks a coffee shop / Well you better change your station ‘cause that ain’t all that we got / Yeah, I want a cup of coffee but I don’t want a GMO / I like to start my day off without helping Monsanto — “A Rock Star Bucks A Coffee Shop”

It’s hard to argue that Monsanto isn’t an evil company: Their horrendous business practices and devastating products are well-documented. But, in this specific case, Young is saying if you drink Starbucks coffee, you’re swallowing a dose of GMO brew. Is this true?

Kind of. Starbucks coffee itself is non-GMO — not by choice, but because GMO coffee beans have yet to take off and become a widely-grown variety. That’s likely to change in the coming decade, but, for now, your Starbucks brew is natural because Starbucks doesn’t really have another option.

But other ingredients are a different matter. Anti-GMO organizations like Green America are specifically pushing to make Starbucks change the kind of milk available in its stores. Currently, the chain buys rGBH-free milk produced by cows that are fed GMO corn, soy, alfalfa, and cottonseed. They’d like Starbucks to start transitioning to serving organic, non-GMO milk.

Now, it’s important to point out here that the milk itself isn’t “GMO” — unless the cow itself has been genetically modified, the milk it produces is still natural (though perhaps not “organic”). If a cow consumes GM corn, it gets broken down during digestion, and those organic materials get reconstituted into new organic materials. The modified genes don’t stay intact and seep into the milk and wreak toxic havoc to the bodies of everyone who drinks it.

So yet again, Young has trouble separating fear from fact.

The seeds of life are not what they once were / Mother Nature and God don’t own them anymore — “The Monsanto Years”

In the last lines of the album’s penultimate track, Young suggests that GMOs are an indication that the seeds we now use to grow our crops are inorganic — that Monsanto and other corporations are now conducting work that has turned our food into some unnatural, unholy substance.

Young seems to be willfully ignorant about the evolution of agricultural practices. For thousands of years already, we’ve selected for specific genes that allow crops to grow bigger, in harsher conditions, with more robust flavor. None of the fruits or vegetables we consume would resemble anything like they do had we not. Genetic modification is just the next step in that, directly changing characteristics so we can grow better crops to meet our changing needs.

And those needs are changing rapidly. In the face of a growing population that’s also confronting the harsh realities of climate change and environmental pollution, GMOs could be a simple way to get food to those communities in need, where existing practices cannot currently meet demands.

It’s a shame to see a legend get wrapped up in these kinds endeavors, but, at it’s worst, The Monsanto Years feels cantankerous in the wrong way. Though the album does nothing to tarnish Young’s legacy of years of good works, it makes it clear that the Canadian singer is no longer a worthy political leader. He’s just a guy with a guitar.