Scientists Find New Gliding, Sort-of-Mammal Fossils

These prehistoric creatures lived 160 million years ago.

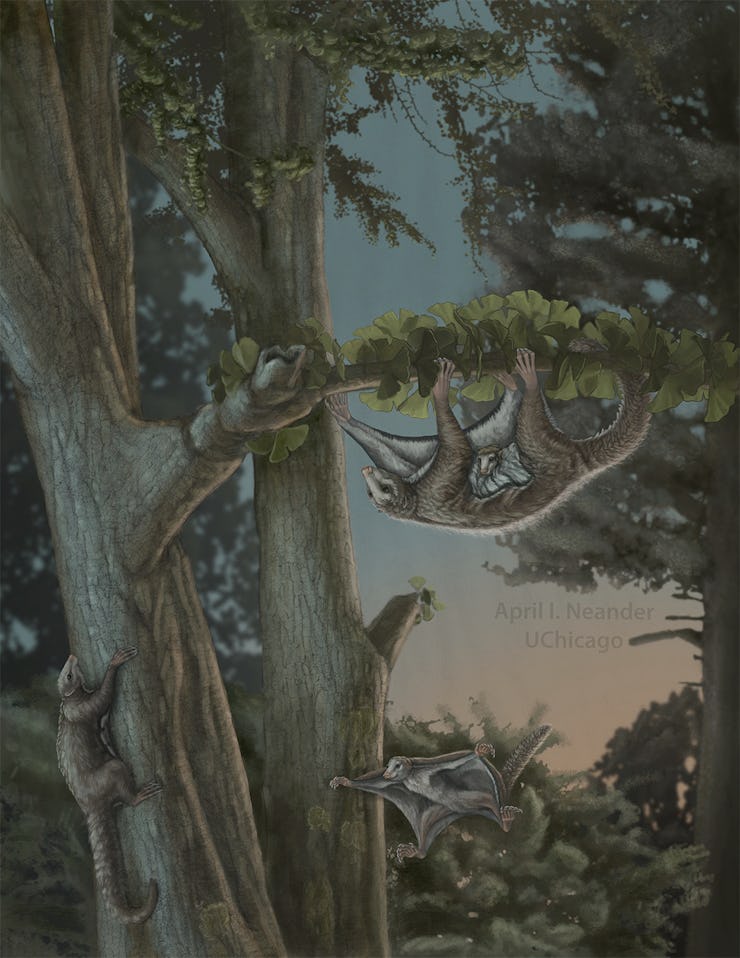

When the the average non-paleontologist thinks of the earliest prehistoric relatives of mammals, they might imagine small rat- or weasel-like animals scurrying under the feet of dinosaurs, feasting on scraps. These generalists did exist, more or less, but new fossil evidence suggests that the earliest relatives of mammals — known as stem mammaliaformes — who lived at the same time as the dinosaurs were much more diverse and specialized than previously thought. Some of them even flew (more accurately, they glided). A recent discovery in China shows how these extinct forerunners to modern mammals exhibited differentiation and specialization typically associated with modern mammals.

At an archaeological site in the Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation in China, paleontologists have discovered two previously unknown gliding stem mammaliaformes. The international team published its findings in two papers in the journal Nature on Wednesday. The two animals they describe in the papers, Maiopatagium furculiferum and Vilevolodon diplomylos, lived about 160 million years ago. If this date is accurate, these Jurassic gliders pre-date modern flying mammals by 100 million years. Most importantly, they represent the first known mammal relatives to glide, live, and forage in trees far above the ground.

This fossil of Maiopatagium furculiferum shows evidence of wing-like membranes that paleontologists suspect helped it glide like modern-day flying squirrels.

“The Jurassic gliders likely lived in forests by freshwater lakes, with some tall trees,” Dr. Zhe-Xi Luo, a paleontologist at The University of Chicago and an author on both studies, tells Inverse. “All modern gliders live in open canopy forests. We interpret that the Jurassic gliders lived in a somewhat similar environment.” A major difference between the habitats of modern gliders and these prehistoric gliders, Luo says, is that the types of plant-life were vastly different long ago, since the flowering plants (angiosperms) that now dominate forests had not yet evolved.

Scientists suspect that Vilevolodon diplomylos lived in ferns and other gymonsperm plants, as indicated by their grinding/crushing teeth probably used for eating plant material and skin membrane probably used for gliding.

These newly discovered stem mammaliaformes, or proto-mammals, shared some anatomical traits with modern mammals. But despite this similarity, they didn’t actually get the chance to evolve into the mammals that we know today.

“Both new gliders are part of the haramiyidan lineage that first appeared 210 million years ago during Late Triassic but went extinct 65 million years ago (with the dinosaus),” says Luo. “This haramiyidan lineage (including Maiopatagium and Vilevolodon) is an evolutionarily dead-end, and a side branch on the mammalian evolutionary tree, before the diversification of modern Mammalia. So there are no living descendants of these Maiopatagium and Vilevolodon or other haramiyidans.”

In this sense, modern flying squirrels and bats and the long-extinct Maiopatagium and Vilevolodon represent what’s known as convergent evolution, in which species that develop under different conditions end up appearing or functioning in similar ways. They just happened to converge about 100 million years apart.

In this fossilized Vilevolodon diplomylos, the arrows indicate the imprint of the gliding animal's wing-like membrane.

Luo says one of the most significant impacts of these findings is that they show how much more diverse stem mammaliaformes were than paleontologists previously thought.

“The popular version of this view was that ‘mammals always lived in the shadow of dinosaurs.’ But that was then,” says Luo. “We now know that mammals co-existing with dinosaurs during the Mesozoic had evolved into many ecological specializations.”