The Untold Story of the Woman Who Saved 'Power Rangers'

It took a decade, but Margaret Loesch created a mighty phenomenon.

Twenty-five years ago, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers was the number one television show on the planet. This week, a big screen reboot with a monster budget will hit theaters, reinvigorating a franchise that earned over $1 billion in merchandise revenue in 1995 alone. But if the film feels inevitable — a product of the post-Avengers boom — the truth is that it took a lot of dedication and some impeccable timing to make any of this possible. Three decades ago, the Power Rangers was a half-baked idea languishing on VHS tapes bootlegged in Japan. They had few supporters, but when it came down to it, there was only one that really mattered.

The Power Rangers may have saved Earth 839 times — at least once for every episode — but Margaret Loesch saved the Power Rangers.

In 1984, Loesch left her executive position at Hanna-Barbera Productions to become CEO of Marvel Productions, the TV division of the famed comic book publisher. Loesch worked closely with the legendary Stan Lee and endeavored to bring Marvel’s superheroes to the small screen. While everyone’s clamoring to adapt B-level heroes to TV now, back then, networks hated comics. “Executives felt only 18-year-old boys were reading comic books, nobody else,” recalls Loesch. Aside from outliers like The Incredible Hulk and The Amazing Spider-Man, which came before Loesch arrived, “nobody wanted to buy Marvel shows.”

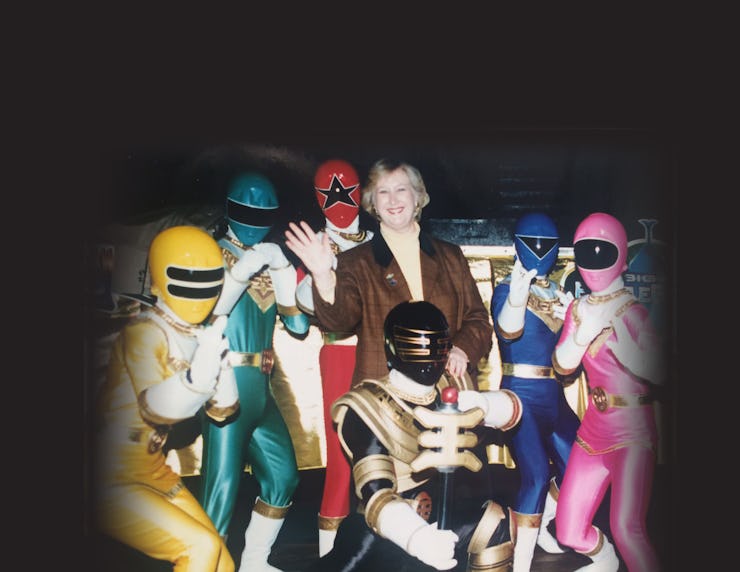

Margaret Loesch (far left), during her tenure as President and CEO of Marvel Productions. She worked closely with Stan Lee (middle) and Marvel CEO Jim Galton (far right) to shop Marvel shows to TV networks, which Loesch says were unsuccessful except in selling non-Marvel cartoons like 'Transformers.' Circa 1986.

The Amazing Spider-Man was canceled after only 13 episodes, but it became such a massive hit in Japan that Stan Lee became a household name in the country. Gene Pelc, Marvel’s “Man in Japan” in charge of licensing, leveraged Lee’s celebrity to get a meeting with Yoshinori Watanabe of the Toei Company, a Japanese studio with its own superhero universe. Toei’s offerings included Kamen Rider, a brawler who rode a motorcycle and dressed like a grasshopper, and Johnny Sokko, a boy who controlled a flying robot. And soon, Toei would introduce Super Sentai, a five-person task force of superheroes that became the forerunners to the Power Rangers.

Toei entered into a cultural exchange of sorts with Marvel, with the companies trading the right to use the other’s characters. In 1978, Toei produced its own version of Spider-Man, adding a kaiju flair — Spidey had his own giant robot — and in return, Marvel received permission to repackage original Toei properties for western audiences. This was long before the internet made these things broadly accessible across oceans when often, heavy-handed repackaging and re-contextualizing was the only way to import culture to new audiences. Lee was fond of one in particular: a trio called the Sun Vulcan.

The Sun Vulcan were the latest heroes in a growing anthology franchise. Super Sentai, created by manga writer Shotaro Ishinomori, followed the weekly adventures of five young people who transform into superheroes and fight evil with martial arts and their giant robots. It kicked off in 1975 with Himitsu Sentai Goranger, which featured a secret squad formed by the United Nations to fight terrorists called the Black Cross Army. After 84 episodes, the show rebooted and adopted new characters, costumes, and a new title. This change became an annual procedure that continues today. The series that Lee loved was 1982’s Taiyo Sentai Sun Vulcan, which had heroes whose costumes and robots were inspired by safari animals. It also happened to have been co-financed by Marvel, with Pelc handling whatever creative responsibilities were required.

“Stan brought me this video and said, ‘Maggie, I think this is a hit. You need to look at it,’” Loesch remembers. “I thought it was funny and different, but it was in Japanese. I called Stan and said, ‘Stan, it’s all Japanese.’ He says, ‘I know! But isn’t it great?’”

'Taiyo Sentai Sun Vulcan,' a 1981 series in the 'Super Sentai' franchise, was originally eyed by Stan Lee to become a Marvel television series in the United States.

A year later, Loesch and Lee allocated $25,000 to make a sizzle reel of Sun Vulcan to pitch to American networks. Lee wanted to dub the show in English to keep costs down and emphasize the comedy. “It was nothing like what was on television,” says Loesch. The closest comparisons she could think of were The Lone Ranger and Creature from the Black Lagoon, which mesmerized her as a kid, even with the cheap costumes and campiness. Sun Vulcan was unique and modern but still retained that cheesiness. “Stan and I liked the cheesiness. I thought it was funny and that kids would like it.”

Loesch’s instincts were correct; as Marvel pitched Sun Vulcan, Super Sentai aired unedited in local stations in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Honolulu, and other cities with significant Japanese populations. It gained a small but enthusiastic audience. Among the fans was August Ragone, now a Japanese pop culture expert and author who grew up watching the series with friends in the late 1970s. The show was sponsored in America by the Marukai Trading Company, a retail chain that sold imported Sentai toys all around California and the U.S. Ragone was a frequent customer, filling his bedroom with plastic Japanese heroes.

“All the kids I knew that were watching, we all lost our minds,” remembers Ragone, who grew up in San Francisco. “We came up with this motto: The only thing that mattered in life were Japanese superheroes.” Ragone and his friends joked they were “the only four people in the country who cares about this stuff.”

The networks didn’t know how many kids were watching Sentai, either, and so they doubted that Marvel’s hodgepodge of Asian robots and karate would appeal outside the West Coast. Deeming it “too violent” and “too foreign,” development departments rejected Marvel’s pitch for Sun Vulcan. Loesch remembers one executive asking her: “How could you show this junk?”

Loesch knew well in advance that violence would be an issue. “We tried to downplay some of the violence, the direct karate chops to other characters,” she says. “We would always show the karate chops to the monsters, not to any human person.” But the changes weren’t enough.

“Stan and I were very discouraged and a little embarrassed,” Loesch says. “We thought this was funny and different. Anything where teenagers are empowered; we know from X-Men what a great formula that is.”

Ultimately, Marvel failed to launch what would become a phenomenon a decade later. In 1985, Lee relinquished the rights to Super Sentai back to Toei. Loesch spent five more years at the company.

Margaret Loesch and Stan Lee, along with Spider-Man and singer Donny Osmond (far left).

A few years later, Israeli music producer Haim Saban watched Super Sentai in his hotel room while in Japan. He too saw its potential, so he scooped up the rights for his new company, Saban Entertainment, and produced a pilot. Like Marvel years before, Saban was rejected by the networks — until he met Margaret Loesch.

In 1990, Loesch was recruited by the new Fox Broadcasting Company to assemble a daily children’s block, the first of its kind on TV. Most kids’ blocks were on Saturday mornings, but Loesch wanted to attract kids before and after school. On her last day at Marvel, Loesch vowed to her old colleague that they would work together again. “I’m going to put on all the shows I believe in that we couldn’t do,” she remembers telling Lee. “We’re going to do X-Men the way it should be done. We’re going to do Spider-Man the way it should be done.”

Loesch spent the next few years trying to make good on her word, but the odds were stacked against her when she joined Fox. The network, established in 1986 by Rupert Murdoch, was roundly mocked and dismissed for daring to compete with the big three broadcasters. “People felt another network couldn’t succeed.”

Loesch was looking for something edgy to put the fledgling network on the map. Production was already underway for X-Men, the hit animated series that would lay the groundwork for the Hollywood movie franchise, but Loesch needed one more surefire thing. And Fox, like the other networks, were hesitant to take in too many comic book shows. Saban, who had done business with Loesch earlier, offered a look at his company’s projects.

Sitting in a room with a foot-high stack of tapes, Loesch rolled her eyes at the “soft, young programming” Saban had in development. She told him that to counter-program for weekday mornings at 7:30, she wanted something funny but also loaded with action to attract boys, “because the other networks were going with girls.” Saban excused himself and rushed off to retrieve another VHS tape. He returned out of breath, popping in the tape and telling Loesch not to get mad about what she was about to see. “Nobody likes this,” he said. “But I think it fits what you’re describing.”

On the tape? Super Sentai, the same show Lee had optioned from Toei all those years ago. “I didn’t even finish,” Loesch says. “I went to Haim and I said, ‘This is it. I’ll take it.’” In the fall of 1992, Margaret Loesch and Fox Kids green-lit what would become Mighty Morphin Power Rangers to air in the late summer of the following year.

By Christmas of 1992, Saban’s staff was plotting episodes based on footage they could use from the most recent Sentai series, Kyoryu Sentai Zyuranger. That edition featured the now-iconic dinosaur robots and sleek costumes with eye-catching diamond patterns. But while the toys it would inspire were great, its story was unadaptable.

In Zyuranger, the heirs of five kingdoms awaken in the present day to fight the sinister witch, Bandora, with the support of their mentor, a wizard elf who adopts the identity of an apartment landlord in Tokyo. Steeped in Japanese mythology, Zyuranger wouldn’t fly on its own on American TV, so a complete rewrite was necessary. In place of the medieval stuff was a new story, set at a California high school. A clique of trendy teenagers dealt with typical problems like homework, football games, and neighborhood pollution, all while being secret superheroes. It was peak ‘90s America.

Top: The cast of Toei's 'Kyoryu Sentai Zyuranger.' Bottom: The cast of Saban's 'Mighty Morphin Power Rangers.'

In Power Rangers, a space witch named Rita Repulsa is let loose with her minions and resumes her plan to take over Earth. An alien wizard named Zordon summons five teenagers from Angel Grove and grants them access to an ancient power to save the world. Armed with weapons and war machines called Zords, these kids — brawny Jason, cool dude Zack, serene Trini, brainy Billy, and “it” girl Kimberly — become the Power Rangers, the first of many crews to kick alien butt every week on TV.

David Yost, who landed the role of “Billy” (he wore blue) after eight rounds of auditions, said he and his castmates weren’t shown footage from Zyuranger, and didn’t grasp the concept of their show, even while filming. “We were kind of distant from the superhero aspect until we saw the pilot cut together,” he tells Inverse. “We didn’t see it until we started voice work, when we’d put our voices over the action. That’s the first time we put the puzzle together.”

In addition to the plot changes, Loesch wanted more humor to even out the violence, which was still too prominent. “I was getting so much flak about it. I asked Saban to create secondary characters to take the emphasis off the action,” Loesch says. Her mandate led to the creation of Bulk and Skull, the bumbling bullies of Angel Grove High. They became fan favorites and stayed on the show for six seasons, an unprecedented run for a series with so much turnover.

Filming the action was a major endeavor. Though Power Rangers recycled fight scenes from the Japanese version, new fight scenes were still necessary. Problem was, production couldn’t figure out how to choreograph kid-friendly combat with stuntmen wearing the heavy costumes. Playing the Putty Patrol — Rita’s golem army — required its own body language. This necessitated bringing over the stunt team from Japan to teach and fill in until the domestic crew could master it. “Those stuntmen had really been highly trained, and we couldn’t get regular stuntmen over here [to learn]. So they had to bring the Japanese over to play Putties because they couldn’t play them.”

As production progressed, the months leading up to the August 1993 premiere were tense for Loesch, who fought doubt from the network, her own team, and after all these years, herself. Despite Super Sentai enduring in its native Japan, no one on Loesch’s side of the Pacific saw the potential. “Even my staff hated it,” Loesch remembers. Audience data from test screenings were “through the roof,” but people weren’t buying the data. “It tested so high that nobody believed it. They said it’s faulty testing. That can’t be,” she says. “That’s what gave me the confidence to continue to fight for it all the way up to the end.”

Fox’s network chairman Lucie Salhany sent Loesch a telex saying that four of the biggest affiliates refused to air Power Rangers on the basis of its violence. It got worse when a presentation for advertisers bombed after Loesch screened a preview of the show. “My head of ad sales came up to me during a break, and he begged me not to show Power Rangers,” she remembers. “I said, ‘I can’t kid them. It’s on the schedule. I’m going to show it.’” Her honesty came with a price: Everyone in the room was “very unhappy.”

Salhany urged Loesch in her memo: “Please, please don’t put this on air.” Loesch lied to her boss, telling her that if Power Rangers didn’t work, she had a backup. “We believed in it, but by that point, we were second-guessing ourselves. That pressure was on me, knowing advertisers hated it and that our big affiliates wouldn’t air it.”

That all changed when the show premiered on August 28, 1993, when most of the target audience was still on summer break. It was an instant hit, compelling Loesch to move the show from its morning time slot to the afternoon, where ratings exploded. Power Rangers, along with Animaniacs, Batman, and X-Men, was a hit for the new network, igniting an arms race for kids’ programming.

The franchise’s rapid ascent was unlike anything that came before it. As the ratings skyrocketed, retailers could hardly keep the toys in stock, which made Christmas shopping into a bloodsport that even inspired the Arnold Schwarzenegger comedy Jingle All the Way. A movie was fast tracked and hit theaters in June 1995. A press conference at Universal Studios, where the Power Rangers were announced as character ambassadors for anti-drug program D.A.R.E., attracted 35,000 to the park and jammed Los Angeles traffic for eight miles. That, Yost says, is when the phenomenon truly became clear to the cast.

“We had filmed almost the entire first season before the show even started airing, so we had no gauge,” he tells Inverse. “We kept hearing the TV show is number one, but we didn’t understand what that meant. We went to Universal to do one tiny little show and suddenly the traffic is backed up on the 101 freeway in each direction. They had to shut Universal Studios down. That’s when we all were like, ‘Oh my gosh.’ After that long day, we went home. We made national news.”

While kids were happy, adults were furious. In 1994, Loesch was confronted in Washington by congressmen who challenged her for the hysterical content in Power Rangers. In 1996, Vice President Al Gore called Power Rangers “sugary” and “sociopathic.” The show ignited a national debate over censorship in children’s entertainment. While Loesch fired back as much as she could, even she admitted to “losing sleep” in G. Wayne Miller’s 1998 book, Toy Wars.

“When I first brought the Power Rangers home and showed my son — he was four — he ran around the house, you know, imitating [the action],” she told Miller. “I put my hands on his shoulders and said, ‘Honey, listen. You can pretend to be a karate champion; you can pretend all you want,’” before adding, “you can’t kick the cat.”

Today, Loesch’s son is 28, is a DJ in Southern California, and has no record of feline abuse. And Loesch sounds like a proud parent when talking about the show: “Whenever I hear young men in particular tell me [about Power Rangers], it is validating, because what I was told in Washington by congressmen and pressure groups was that I, Margaret Loesch, was ruining the hearts and minds of children with this junk,” she says, now laughing.

Junk or not, the Power Rangers have become a nostalgia goldmine. After the show’s 20th anniversary in 2013, a renewed push for Mighty Morphin merchandise surfaced, and a new line was developed with adult-oriented products like shot glasses and yoga pants emblazoned with Power Coins. Collectors vie for sturdy metal die-cast toys put out by Bandai. And, of course, there’s a movie on the way. It’s rated PG-13, which won’t stop today’s children from seeing it, and may even encourage adults to spend a Saturday at the multiplex, feeling like a kid again.

Loesch’s oversight of Power Rangers became less rigorous as the show became the phenomenon that she, Saban, and Stan Lee hoped it would. After the first season, Loesch’s limited herself to consultation over major changes. Like its Japanese counterpart, Power Rangers embraced yearly rebranding. “Once the show was established, after the first year, it was not as necessary for me,” she said of her involvement. “I stopped reading the scripts after the first season.”

But Power Rangers is still Loesch’s legacy. Just as much as she helped define the Power Rangers, the Power Rangers would define her. In 1997, amid reshuffling at the network she built, Loesch left Fox Kids with a billion-dollar franchise in her portfolio. She leveraged her reputation as a TV pioneer to became president of Jim Henson Television, where she rebranded the no-name Odyssey Network into the Hallmark Channel. After establishing The Hub with Hasbro and Discovery in the early 2010s, Loesch was enlisted by Genius Brands to oversee Kid Genius, a youth-oriented VOD channel. Among its offerings: an animated feature film of Stan Lee’s Mighty 7. True to her word, Loesch got to work with her old friend once again.

Power Rangers evolved under Saban until Disney came knocking. As part of a buyout of Saban and Fox’s joint venture channel Fox Family in 2001, Saban sold the Power Rangers to Walt Disney. While they always defeated alien invaders, they couldn’t stand up to a key, influential demographic — mothers. Their distaste for the franchise led to the Power Rangers’ slow demise, as they became a black sheep in the company’s portfolio. The Rangers were relegated to a corner at Disney’s parks and aired at odd hours, almost exclusively on premium cable channels. By the end of 2009, Power Rangers was canceled, but in the summer of 2010, Saban regained ownership, fast-tracking a new season to air the following year. The Power Rangers have continued fighting evil since.

Yost understands that without Loesch, none of this would have happened. “She was the one person from Fox that believed in the show when everybody else was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ We owe her so much cause she got it on the air.”

Kids glued to their TVs more than 20 years ago are now adults who will line up — some with their own children — to see Dean Israelite’s Power Rangers. Loesch, now watching from afar, feels validated knowing the world sees what she saw almost 30 years ago while at Marvel. “I’m delighted a new movie is coming out, and I hope it’s good,” she tells Inverse. “I hope they captured the magic we had in the series. I know that sounds funny, but there was an innocent quality about the show. It’s every kid’s fantasy to turn into a superhero.”