Why Hasn't Technology Ended the Housing Shortage Like Robert Heinlein Predicted?

In 1952, Heinlein predicted that technology would end the housing shortage. What happened?

“In fifteen years the housing shortage will be solved by a ‘breakthrough’ into new technologies which will make every house now standing as obsolete as privies.” - Robert A. Heinlein, 1952

In 1952, Robert Heinlein made a series of predictions in an article in Galaxy magazine regarding the end of the twentieth century. Some of them were logical; others were fanciful. He talked about interplanetary taxis, extreme medical breakthroughs, and predicted Martian suburbs would crop up like mushrooms. To be fair, he also envisioned cell phones. He was a smart guy even if he was a bit out of his depth.

Somewhere between discussing deep space travel and the future of phoning home, Heinlein spoke about housing. This was significant at the time because America was in the midst of a housing shortage. World War II and the GI Bill had radically expanded manufacturing, creating a middle class without creating an appropriate place to put it. The Housing Act of 1949 had all but guaranteed a pot for every chicken. Heinlein predicted a technological solution.

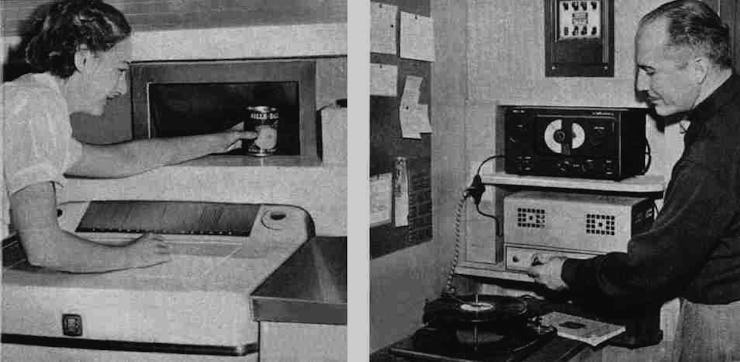

The Monsanto House of the Future

Heinlein was vague about the nature of technology but certain that a material or new arrangement would solve the problem. He was far from alone in this regard — though perhaps unique in his confidence. But did it happen? Not really. Urban slums remain a fact of life and many of the factory towns that thrived in Heinlein’s day have now fallen on hard times. No fabrication technology or new type of housing ever fundamentally altered the housing market.

Part of it comes down to population and population density. Housing shortages are the worst is in large cities, which grow on top of aging infrastructure. A quick look at San Francisco’s housing crisis, a particularly extreme modern example of a shortage, suffices to make the argument that technology is more likely to be the source of issues (cough, AirBnB, cough) than the solution to them. If anything, technology has facilitated gentrification by allowing the wealthy to parachute into old neighborhoods in order to snatch up investment properties. The affordability of housing, as it turns out, has little to do with housing and everything to do with location.

There is finite valuable space and the rich have a nasty tendency to hoard it. New building technologies could allow for them to share, but sharing would diminish the value of real estate so it’s unlikely to happen. If Heinlein understood that disruptive potential of technology, he misunderstood who would be empowered to switch it on.

The biggest problem with housing outside of cities is size. Americans tend to fetishize square footage. Large houses built on private lots exacerbate sprawl, minimizing the number of homes near business districts and attracting commuters uninterested in the sort of local infrastructure that creates employment opportunities for those willing to live slightly farther from centers of wealth. City dynamics leak into the suburbs even as rural areas remain unappealing to developers because of lacking job opportunities for potential buyers.

A diagram of a modest American home, an oxymoron.

What Heinlein failed to understand was that the housing shortage has less to do with our ability to build effectively and efficiently, and more to do with the fact that we suck at creating affordable spaces. We sucked at it in 1949 and we suck at it now. It’s not a technology problem; it’s a social problem. On some fundamental level, it is a problem with how Americans practice capitalism.

Maybe if we’d found a way to use technology to create a sustainable affordable middle ground in cities, Heinlein would’ve been right. Maybe if we found a way to answer demand with a reasonable uptick in supply, we wouldn’t see skyrocketing prices and continuing housing shortages. Maybe in an alternate future.