Benjamin Franklin's Bold 'Antediluvian' Life Expectancy Prediction Will Be Wrong

In 1780, Benjamin Franklin predicted that, in 1000 years, humans would have life expectancies in excess of 900 years. Nope.

In Alternate Futures, we take a look at incorrect predictions from the past in order to better understand what we can foresee and what we cannot.

“All Diseases may, by sure means, be prevented or cured, not even excepting that of Old Age, and our Lives lengthened at pleasure even beyond the antediluvian Standard.” - Benjamin Franklin

In February of 1780, Benjamin Franklin penned a letter to Joseph Priestly, an English philosopher, with this prediction for the future. There were a fair number of other predictions, too, but let’s unpack one thing at a time, starting with Franklin’s optimistic outlook for our life expectancy.

First, a little context. Franklin begins this discussion with: “The rapid Progress true Science now makes, occasions my Regretting sometimes that I was born so soon. It is impossible to imagine the Height to which may be carried in a 1000 Years the Power of Man over Matter.” Obviously, we’re nowhere near 1000 years removed from Franklin’s world of 1780, but we’re also nowhere near the described “antediluvian standard.”

“Antediluvian” is a term that comes from the Latin words “ante” and “diluvium” (obviously) and means “before the flood.” A biblical reference to the time before the great flood (that’d be the one with the Ark), is used here to describe the absurdly long lives of the Old Testament players in the Bible. The antediluvian patriarchs, including Adam, Seth, Noah, and Jared, all lived in excess of 900 years.

There is a theory that it’s just our interpretation of the numbers in Genesis 5 that give us these crazy life expectancies, but let’s assume that Franklin was going by the book and predicting based on the straightforward reading of pre-flood lifespans. A life expectancy of 900 years or so sounds pretty far-fetched, even on a generous 1000 year timeline. So what made Franklin think it was within the realm of possibility and what did he miss?

In short, Franklin was blinded by progress. Going back to the beginning of this discussion, Franklin says, “The rapid Progress true Science now makes, occasions my Regretting sometimes that I was born so soon.” The 18th century, while archaic by our standards, was a time of burgeoning innovation. Steam engines, telegraphs, flush toilets, submarines, and steamships all came in the time before Franklin wrote this letter, and the Montgolfier brothers invented the hot air balloon just 3 years later. We’d come a long way in a short time, and Franklin’s comment on “rapid progress” reflects that. And so, he assumed that progress would continue at roughly the same or higher rate.

He wasn’t totally wrong. A look at the leaps and bounds that science and technology have made over the last nearly two and a half centuries is evidence that progress has continued to forge ahead, giving us things like modern appliances, the internet, commercial air travel, mobile devices, drones, A.I., and even self-driving cars.

That said, Franklin’s assumptions about how we’d use innovation and where we’d direct our energies was a bit off.

Medicine has come an awfully long way since 1780, but our progress has largely taught us that our human bodies are almost laughably fragile. We’re a weak, delicate species and though we’re more resilient than ever before thanks to advanced medicine, our bodies are still delicate ecosystems that inevitably break down. Though Franklin was partially right in his prediction that we’d come a long way in fighting disease, thus far we haven’t found a way to stop the relentless march of time and its affects on our flesh analogs, and we’re still very vulnerable to a host of maladies.

The other point of Franklin’s inaccuracy has more to do with human nature than the human body, though. Namely, Franklin didn’t account for the perpetuation of the time-honored human tradition of being really damn cruel to one another and the effect that might have on progress.

Franklin ends this discussion of progress with a sort of recognition that we advance much more quickly in science and technology than we do in humanity, saying, “O that moral Science were in as fair a Way of Improvement, that Men would cease to be Wolves to one another, and that human Beings would at length learn what they now improperly call Humanity.”

Though Franklin does cede that modern society has mostly turned men into monsters and that we humans are sort of inherently garbage to one another, he might’ve underestimated the degree to which our awfulness has impeded our progress. Problems of inequality and extreme self-interest have always stood in the way of widespread and meaningful progress, and we’ve failed to fix those problems, instead allowing them to hold us back. Access to education, positions of power and influence, and even health care have dramatically affected the ways in which we move forward.

Franklin couldn’t have known then about things like the nightmare that is big pharma and the influence of money on health care and the availability of treatments. He likely assumed that we’d understand that even in the medical field, progress requires us to see beyond ourselves and our immediate problems.

Mostly, though, Franklin’s talk of life expectancy largely ignores one of the most significant threats to long lives of leisure: ourselves.

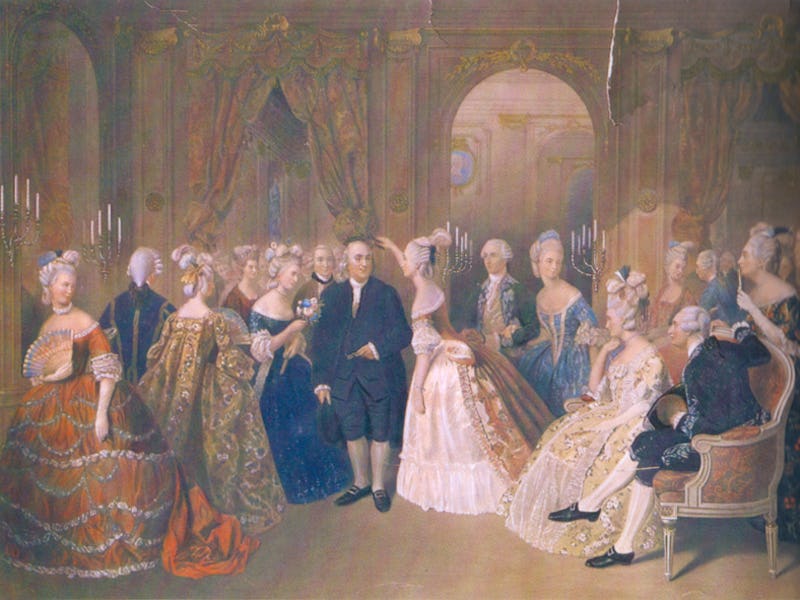

Achille Formis Befani, 'Junge Frau im Schatten'

From guns to climate change, if diseases and illnesses don’t take us out, there’s a good chance that we’ll do it ourselves. We gleefully dole out devastating blows to our environment, fill our air with pollution, neglect life-threatening problems in infrastructure, and, at least in the United States, allow almost anyone to walk around with devastating weapons.

Barring diseases and bodily failures entirely, the odds of surviving 900 years are decidedly not great given the way we threaten our own lives with murder, war, and carelessness. Of course, if we did live for incredible near 1000-year periods, maybe the value that we place on life would be dramatically different. Maybe we’d behave differently toward one another. Maybe we’d finally figure out a way to fix gross problems of inequality and recognize the same-boatness of living on this planet together. Maybe we’d have a little bit of healthy perspective. For now, though, there’s no way to know. Maybe in an alternate future.