The Ubernet Is When Complete Access Kills the Internet as We Know It

Interconnection is not the inevitable end game of total connection.

The term “ubernet” is itself a lazy neologism. It sounds cool, but doesn’t accurately convey its significance, because what separates the theoretical ubernet from the current internet is not that it’s somehow super, but that it’s entirely ubiquitous (“Ubinet” just doesn’t sound cool). Put simply, the ubernet is what will be created when everyone in the world is connected to the internet and the internet is also connected to all of our tools and belongings. It is the word for what happens when the complicated web we’re weaving can grow no further.

In some sense, this is a science fictional notion; in another sense, we’re well on our way. Cloud-connected devices are now standard. Smartwatches are penetrating a new market. The “Internet of Things” is linking household appliances like thermostats and security systems to our phones. Information and date are being generated at historically unprecedented rates. At the same time, cyberspace is becoming a less significant public domain. We sort data and use tools rather than navigating through files. It’s a fundamental shift — and one that, depending on your outlook, warrants celebrating or grave concern.

Let’s start with the concerns. Some thinkers expect the ubernet to facilitate the breakdown of national and territorial borders as we understand them. People will still fight over land because they need resources and space, but the nature of their relationship to that land is likely to change. In a 2014 Pew Research Center survey 2,558 tech experts across the world were asked what they thought about this. David Hughes, the famous pioneer of the internet responded:

“When every person on this planet can reach, and communicate two-way, with every other person on this planet, the power of nation-states to control every human inside its geographic boundaries may start to diminish…. Nations will still have military and police forces, but increasingly these will become less capable of controlling populations.”

Other respondents agreed that conflicts would bloom due to the ubernet, predicting futures involving grassroots warfare with social control institutions, in which technology makes resistance groups stronger. Of course, many were also optimistic that the ubernet would do more good than harm. J.P. Rangaswami, the chief scientist for Salesforce.com said:

“Society as a whole, in government, in the public sector, in the private sector, in the voluntary sector, in academia, in NGOs, and as the common man and woman, will come to recognize that behind the internet is a connected world of people. People who route round obstacles to solve problems in ways that people could not before. With that realisation, we will see people elect to solve problems that have hitherto been the domain of interminable conferences and committees who, for no fault of their own bar their very architecture, could not make any real impact.”

Indeed, many tech experts think the dissolution of borders as we define them today will encourage people from very different walks of life to come together and collaborate on solutions that can be used to solve problems worldwide.

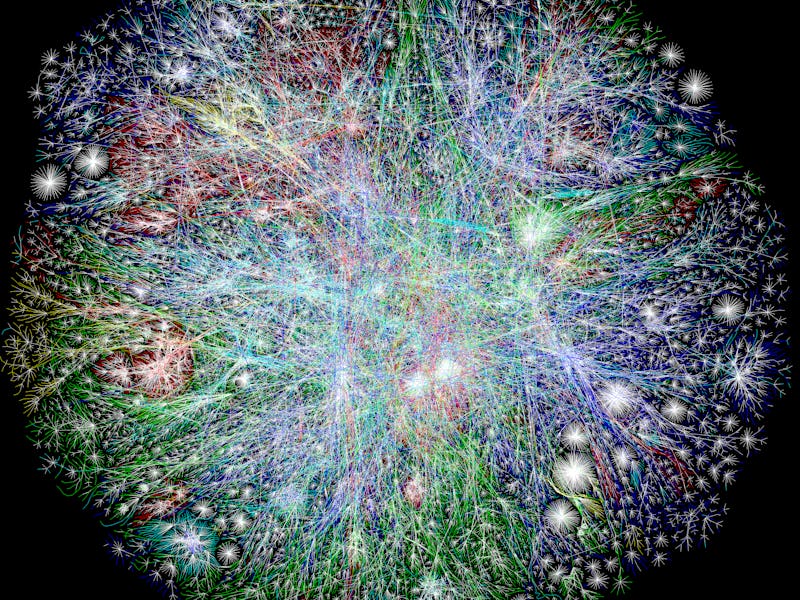

The other big thing we can expect the ubernet to facilitate is the centralization and conglomeration of services. A decade ago, internet traffic was spread out relatively evenly. Today, just 30 or so major services, like Facebook, Google, Netflix, and Amazon account for the bulk of regular traffic. There’s plenty of reason to believe that new companies will gain admission to this pantheon, but the internet we once wandered using Internet Explorer will become a lesser use case for the connections the internet represents. The partial dissolution of net neutrality will likely speed this process as companies prioritize specific information lanes and distribute information instead of making hubs. If the internet was a city with a downtown, the ubernet is a vast sprawl with amazingly effective postal workers. This has been referred to as the “walled garden” effect — with Netflix, for instance, representing an oasis for information consumers. Within the context of worldwide access, this phenomenon promises both a slightly disturbing uniformity of experience and a considerable opportunity to create chaos in the dark places between walls.

The arrival of the ubernet, the thinking goes, will therefore fundamentally change the nature of the human experience, making the relationships between individuals and “mega-sites” of primary importance. Our affiliations will be less geographical than consumerist: Apple versus Samsung instead of American versus Korean. Facebook — or something very much like it — will serve as the public square in a far more literal way than it currently does (though it’s naive to expect friendships to initially bridge social gaps they don’t already).

And, yes, it’s easy to imagine the creation or evolution of one single website that gives you access to 90 percent of what you want or need. Maybe Google will also create the software that runs your smart-car or your thermostat. Maybe Amazon will be able to fix your leaky, connected faucet while you stream the twentieth season of Transparent.

It’s easy to joke these days about our lives being lived mostly in the digital world, but as our lives and the things we use become increasingly dependent on being connected, we’re going to stop thinking about the world geographically and start thinking about it in terms of the websites we subscribe to the most. So maybe the term ubernet is coherent after all. It doesn’t make the internet super, but it will make certain domains rule supreme.