MIT Researchers Propose an Ancient Technology to Store Clean Energy

What's old may become new again.

A new proposal from MIT researchers looks at how firebricks, clay bricks used in ovens as far back as 3,000 years ago, could play a role in fueling a world that’s independent of carbon energy.

What makes a firebrick — a brick made of refractory ceramic material — so ideal for this use is that they’re able to retain heat for long periods of time if properly insulated.

The theoretical system these researchers created, called the Firebrick Resistance-heated Energy Storage (FIRES), would use the bricks as a repository for excess electric energy.

Here’s how it works: Excess energy from wind farms, for instance, could be converted to heat, using electric resistance heaters, and then be transferred to adjoining insulated firebricks. Later, like the next morning, that heat could be used directly or turned back into electricity after it is fed into a generator. Essentially, firebricks are nature’s oldest batteries.

The proposal will appear this week in Electricity Journal, a peer-reviewed policy journal.

One proposed application of the firebrick-based thermal storage system is depicted in this hypothetical configuration, where it is coupled to a nuclear power plant to provide easily dispatchable power.

How Firebricks Were First Used Way Back When

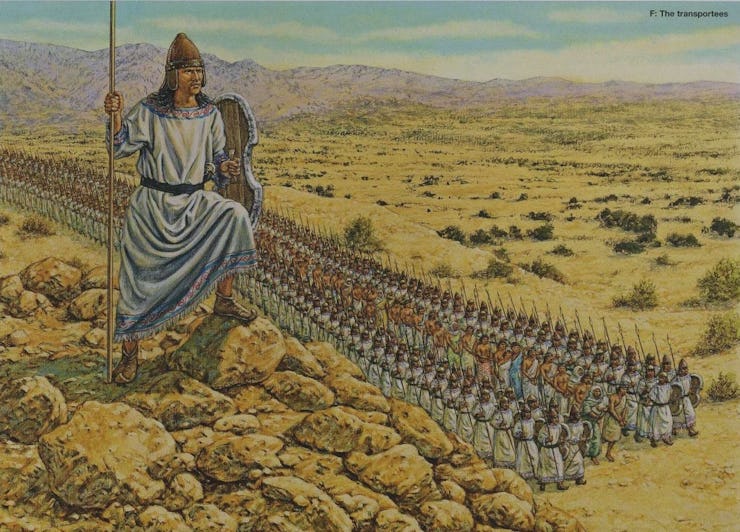

Perhaps the most surprising thing about this discovery is how a firebrick draws on technology that’s so old: It’s believed that firebricks were first created by the Hittites in modern-day Turkey. Made from clay, the firebrick was a big step up from the common mudbrick, which first emerged in Mesopotamia, because it was able to withstand higher temperatures. Some firebricks able to withstand temperatures nearly 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit from this time period have even been discovered intact, a testament to their durability.

Firebricks used in the door of a kiln

Innovative as their new system of energy storage seems, the team of MIT graduate students and an advisor say it could have been created nearly 100 years ago. But in 1917 there wasn’t as much of a use for energy storage as there is today, now that solar, wind, and nuclear power have become more widespread. The biggest issue with using alternative energy sources even more is that within our U.S. electricity market, electrical energy created in these ways is cheap to produce — but storing has prove difficult.

Excess energy is also expensive to store, which keeps it from being economical. Already, researchers say the problem of electricity price collapse is playing out in electricity markets like Iowa and California.

“At times, it is more efficient for energy producers to give energy away free or even pay consumers to take their power plants’ generation than to curtail production because the shutdown and startup of the plant may cost them more,” Jeff Bladen, the Market Services Executive Director for the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, told industry trade publication UtilityDIVE.

That’s where firebricks would come into play. Since the heat they can hold can be sold or repurposed for a profit, their use in this kind of system could theoretically set a limit on electricity market price and incentivize these carbon-free sources of power.

Of course, this is all theoretical for now. Existing resistance heaters that would be needed within the MIT-proposed system only heat up to about 1,560 degrees Fahrenheit. One potential solution would be making the firebricks themselves electrically conductive. Another more ambitious aspect of the system is the potential for turning the heat absorbed by the firebricks back into electricity, which the researchers hope to explore in the next version of FIRES.

If you enjoyed this article, you might enjoy this video on a 99 million-year-old dinosaur fossil.