Could microchipped employees become the future of the workplace?

“A well-designed implant is frictionless, managementless, and becomes part of who you are.”

Imagine unlocking a door with your hand, hovering your palm on your computer to access secure files, or purchasing lunch with a wave — all without a smartphone, card, or dongle.

These things are all entirely possible, but there’s a catch: you’d have to have a long-grain-of-rice-sized device inserted into the space between your thumb and pointer finger via a piercing needle (see a video of a procedure here).

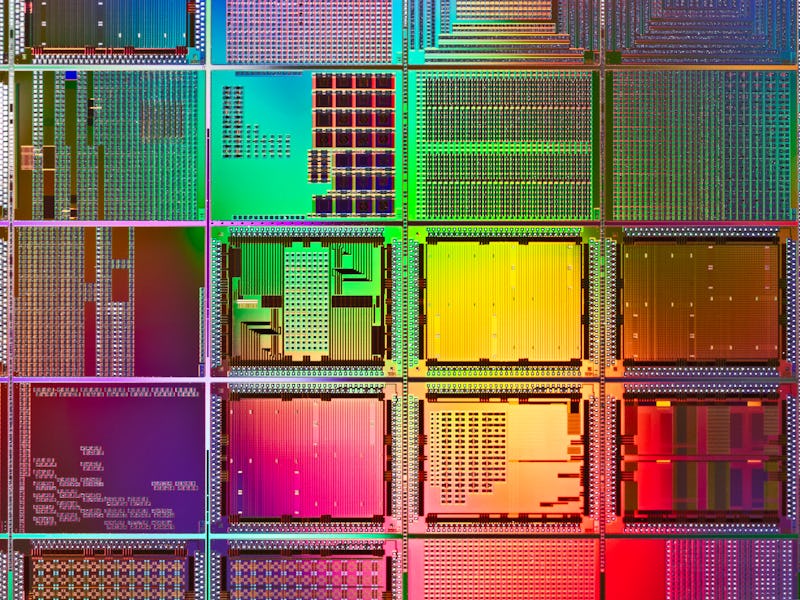

These so-called insertables (the name preferred by academics) utilize RFID (radio-frequency identification) and NFC (near-field communication) technology to interact with card readers, payment terminals, and other devices — similar to what’s built into contactless credit cards, your smartphone, or the identification chips people install in their pets. Insertables don’t require an energy source; they work by transmitting a unique identifier that is read by other devices. (There are many insertable devices for medical purposes.)

Proponents of insertables, which include CEO and founder of Dangerous Things and Vivokey Technologies, Amal Graafstra point to numerous advantages of the devices compared to existing technology. Unlike cards and dongles, individuals can’t lose insertables, meaning they can’t be appropriated by bad actors who want access to homes, offices, and secure data. Of course, having a device physically inside a person’s body prevents them from simply forgetting their card or keys.

Then there’s biometrics, the data created by our faces and fingerprints. These inputs can also be misappropriated by bad actors, sometimes with a simple photo of a face or finger. Worst of all, however, is that while you can replace a card, you only have one face and one set of fingerprints. There are also questions around who controls the data — whether that’s a private company or a government.

“A well-designed implant is frictionless, managementless, and becomes part of who you are,” said Graafstra, who inserted a chip into his hand in 2005. “The only problem people have is a skin barrier. Somehow that’s blasphemous.”

But getting over that hump could lead to huge savings and productivity gains for companies. If enough employees of a company choose to get an insertable, it would eliminate the need for cards, code generators, and other expensive cybersecurity devices. And because employees can’t lose them, they wouldn’t waste time that could be spent working in cases of lost and stolen IDs, and IT staff wouldn’t have to institute security measures to remove access from the old devices and issue new ones. Insertables also have benefits for remote employees.

“If we’re going to be socially distant and out in the field, they’ll be more risk to data security and employees having to prove their identities,” Graafstra said. “A chip that a user owns brings a lot of benefits to costs and security.”

Breaking the skin

Insertables aren’t new technology — they’ve been around for the past two decades.

“The first forays into human microchip implantation occurred in 1998 with Kevin Warwick implanting himself with an RFID capsule in his Cyborg 1.0 experiment,” wrote University of Melbourne researchers Kayla J. Heffernan, Frank Vetere, and Shanton Chang in their 2017 paper Towards insertables: Devices inside the human body. “Warwick’s chip opened doors and activated lights in his office for the duration of the experiment. The same year artist Eduard Kac self-inserted RFID microchips in an art piece entitled ‘Time capsule.’”

The community remains a niche, but it’s received a lot of attention over the past three years. In 2017, vending tech company Three Square Market made waves by becoming the first US company to offer to insert microchips in its employees' hands that would open doors, unlock computers, and make payments on its self-checkout software. More than 50 employees agreed to the procedure. Three Square Market, which did not respond to a request for comment, wrote in a blog post that it was inspired by a partner based in Sweden.

In that country, “thousands have had microchips inserted into their hands. … So many Swedes are lining up to get the microchips that the country's main chipping company says it can't keep up with the number of requests,” NPR reported. Insertables are so popular in Sweden that one of its largest train operators allows passengers to use their chips instead of tickets.

Swedes are typically more enthusiastic about new technology than Americans, although the percentage of the population with insertables there is still relatively low. Graafstra said there haven’t been many US companies that have shown interest in insertables.

“Generally speaking, companies are rare. They don’t really approach us,” he said. “What usually happens is a private customer will bring their implants into a company environment to get access to a controlled environment.”

Part of the reason why insertables remain niche is unfounded fears that they could be used to track people. At least seven states have even passed laws stating that companies cannot force employees to be microchipped — which even enthusiasts such as Graafstra agrees with. However, at the moment, insertables do not contain any GPS technology, and while it is possible to implement it into an insertable, according to Graafstra, it would be prohibitively expensive.

Rather, what’s holding back this technology is the perceptions around it, said Cindy Hsin-Liu Kao, assistant professor and director of the Hybrid Body Lab at Cornell University. She gave the example of Google’s most famous failure, Google Glass, which people found both disturbing and funny. Kao suggested that an interim technology, such as tech-enabled temporary tattoos (the focus of her work), may help transition people into insertables.

“Starting with a form factor that’s removable is a good first step,” she said. “Testing a temporary tattoo and wearing it for a quarter could ease people into insertables.”

Kao said that tattoos weren’t socially acceptable until the 1990s, when many celebrities began embracing body art. Meanwhile, the University of Melbourne researchers pointed out that people’s acceptance of technology has also changed over time. It may take years, but if enough people embrace insertables, it may eventually become the norm.

“My understanding of the implant game is it’s a slow game,” Graafstra said. “It’s going to take a long time.”

This article was originally published on