9 years later, Elon Musk’s biggest pipe dream may finally come true

Nine years since he first had the idea, Musk may finally try to build a Hyperloop.

In 2013, Elon Musk had a singular idea to revolutionize intercity transport — and it had nothing to do with Tesla. Instead of self-driving electric vehicles ferrying people to and from the office, he proposed a system of tubes in which pods would ferry people at incredible speeds of up to 760 miles per hour.

Musk called the system the Hyperloop. And then he… didn’t do anything with it. Flash forward nine years later, and finally, we may be on the verge of seeing what an Elon Musk-built Hyperloop actually looks like and how it might work.

In a tweet posted in April 2022, Musk revealed that tunneling firm The Boring Company would “attempt to build a working Hyperloop”.

So, could we finally be gliding towards a tubular transport future?

HORIZONS is a newsletter on the innovations of today that will shape the world of tomorrow. This is an adapted version of the May 5 edition. Forecast the future by signing up for free.

What is the Hyperloop?

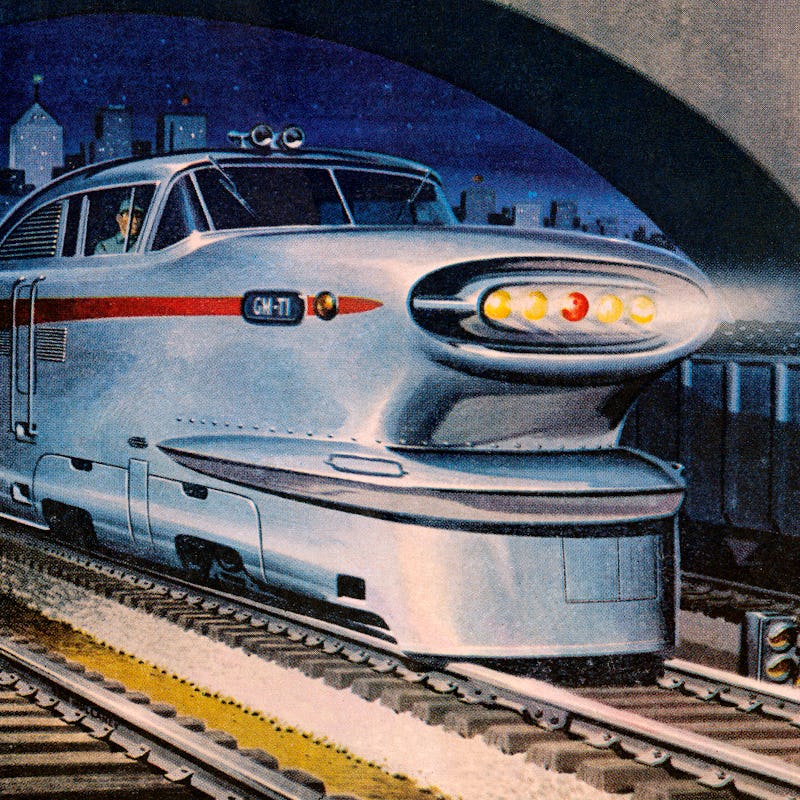

A concept illustration of a Hyperloop.

Musk’s original idea was a response to a planned new high-speed railway line in California. At the time, Musk wrote this attack on the idea:

“How could it be that the home of Silicon Valley and [NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory] — doing incredible things like indexing all the world’s knowledge and putting rovers on Mars — would build a bullet train that is both one of the most expensive per mile and one of the slowest in the world?”

He believed he could do better: Pods containing passengers would speed through 4 meter-wide, wholly-enclosed metal tubes that would be kept in a near-vacuum. The pods would levitate on the track using magnetism — a technology known as Maglev that essentially nixes friction.

According to Musk’s calculations, the proposed system could propel pods full of people at as much as 760 miles an hour. That speed would reduce the travel time from Los Angeles to San Francisco to just 35 minutes.

“There is a huge difference between demonstrating a technology works and the scalability.”

He proposed Hyperloop as an “open source” transport project, analogous to how multiple companies and groups develop different flavors of the open-source operating system Linux.

Musk’s idea was not new — the Hyperloop has its roots in two hundreds-of-years-old innovations:

- A technology patent filed in 1799 by George Medhurst, to do with using compressed air as a means of propulsion.

- A 20-mile-long “atmospheric railway,” built by legendary Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel in 1844. (Brunel, in fact, is a rather Musk-like figure: He engineered the first propeller-driven transatlantic steamship and the Great Western Railway, a major United Kingdom transport line.)

After Musk published his paper, several companies took the idea and ran with it, including Virgin Hyperloop and Hyperloop Transport Technology. In 2020, Virgin Hyperloop even gave a public demonstration of their technology, successfully sending some of their employees along their track.

“It’s difficult to distinguish between the smoke and mirrors and the actual developments that are happening,” says Roberto Palacin, a reader in Transport Futures at Newcastle University’s School of Engineering.

The problem with passengers

It may be inpractical to send passengers in a Hyperloop at speed for safety reasons.

It is important to note that the Hyperloop has made some progress: In 2016, The Boring Company constructed a mile-long test track, and in 2020 Virgin published a video of what it called the “first Hyperloop passenger test” in its own 500-meter-long tunnel. But there are still plenty of question-marks hanging over how much progress the secretive technology has actually made.

“There is a huge difference between demonstrating a technology works and the scalability,” says Palacin.

“We can create a near-vacuum in a tube, add a pod, and throw it at a certain speed and brake. That’s great, but that’s not a system. That’s the basic running technology.”

He points to how in addition to the core technology to make the pod move, any functioning Hyperloop would have to develop a control system for managing multiple pods running along the same route at regular intervals. Engineers would also need to figure out how to scale safety systems and operations so they can run safely around the clock.

“Mass transit and transport systems... are very complex socio-technical systems.”

And these issues are every bit as important as engineering.

“Mass transit and transport systems, in general, are very complex socio-technical systems,” explains Palacin.

“There is an element of technology and engineering that still needs to be addressed, but there’s also the interaction of humans with the system.”

There is one particular problem for which none of the companies working on the technology have a solution

“The fundamental problem with Hyperloop as a system is capacity,” says Gareth Dennis, a U.K. railway engineer.

“In all countries that have a reasonably well-regulated railway it is illegal to have trains running within each other’s braking distances,” explains Dennis.

“For a system as fast as Hyperloop that gives you about maybe 36 to 40 seconds minimum between trains. You might think, well, that doesn’t sound like very much, but bearing in mind that the systems that all of these companies — whether it’s Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, Virgin Hyperloop, or TransPod — all of them have been proposing pods that seat in some cases [only] up to about 30 or 40 passengers.”

In Dennis’s view, what makes Hyperloop unworkable is that the number of passengers a Hyperloop system would be capable of carrying would be many times fewer than a traditional railway. Hyperloop will only be capable of carrying between two and four thousand passengers per hour in either direction, compared to traditional high-speed rail which can handle as many as 20,000 (and shorter commuter railways can handle many multiples more).

“From a passenger perspective, the capacity of Hyperloop is useless,” says Dennis.

Getting to the Freight of the Problem

It is possible sending freight by Hyperloop is more viable.

Earlier this year, Virgin Hyperloop made a dramatic announcement: The company is pivoting to focus on moving freight.

Hyperloop Transportation Technologies has also announced a freight project based in the port of Hamburg, which it claims will be able to shuttle 2800 standard shipping containers per day.

“Hyperloop systems would not only support passengers, but also high-priority, on-demand goods, allowing deliveries to be completed in hours versus days with greater reliability and fewer delays,” writes Jay Walder, Virgin Hyperloop CEO in a press release announcing a partnership with Dubai-based supply-chain company DP World.

Hyperloop “can shrink inventory lead times, help reduce finished goods inventory, and cut required warehouse space and cost by 25 [percent],” Walder says.

“By and large freight just needs bulk and it does not need speed. And that’s the opposite of what Hyperloop does.”

On paper, freight makes much more sense than does passenger transportation.

“Freight can put up with greater accelerations,” says Hugh Hunt, a professor of Engineering Dynamics and Vibration at Cambridge University.

“I can only subject humans to a certain amount of distress. Whereas I can subject refrigerators to greater distress,” Hunt says.

“Also, I can pack the refrigerators into one of these pods and leave them there for a few hours until it’s ready to go.”

If they’re full of freight, then pods don’t need to supply oxygen and freight can’t complain about delays disembarking at the end of the journey.

Future transportation expert Palacin argues that Hyperloop could conceivably even improve the existing freight logistics model.

“The movement of cargo and cargo boxes out of ports requires an awful lot of infrastructure,” Palacin says.

Hyperloop could conceivably zip incoming container traffic away from crowded ports to somewhere more centrally located in a given geography, where containers could then be sorted for distribution, he says.

Rail engineer Dennis is more skeptical.

“By and large freight just needs bulk and it does not need speed. And that’s the opposite of what Hyperloop does,” says Dennis.

Dennis argues that the main problem isn’t the Hyperloop technology perse, but how that technology fits into how the world actually functions. He’s particularly bewildered by Virgin’s deal with DP World, a Dubai-based freight company, to build Hyperloops to move cargo from ships inland.

“The lion’s share of the journey is by ship and that’s not changing anytime soon,” says Dennis. He also notes that there isn’t enough steel in the world to build Hyperloops long enough to remove container ships from supply chains. Freight is also just not as lucrative as moving people, he adds.

“It’s very difficult for freight to justify major linear infrastructure investments and Hyperloop is absolutely no different to that,” says Dennis.

On the horizon…

We’re still a little far away from a tube-filled future.

There are no further details on exactly what The Boring Company is planning beyond Musk’s tweet. But if Musk is to be believed something will happen. So is there still hope for a Hyperloop-propelled future?

Palacin believes the reality may be less eye-catching.

“My hypothesis is that this is going to be a testbed for a number of technologies that are going to be really relevant for other transport modes in the coming decade or two,” he says.

Just as NASA’s space program in the 1960s led to the creation of several technologies that are used everywhere today, the real legacy of Hyperloop may be in innovations that feed other industries, he says.

“I think the magnetic levitation or semi-magnetic levitation — all the magnetic propulsion that is being used in there — could be really relevant for next-generation braking systems for railways for instance,” he speculates.

Dennis is unconvinced, saying: “there is no viable positive case for Hyperloop having any application at all, it's just useless.”

Hunt is more optimistic because of the number of companies still involved in the space — however quiet they are in public.

“I think it is very important in the early days of this type of technology that there’s competition because things don't happen quickly or safely or effectively unless there is competition,” he says.

“I’m pretty sure it’ll be somewhere in ten years’ time. Whether it’ll be everywhere in 20 years’ time is a good question.”

HORIZONS is a newsletter on the innovations of today that will shape the world of tomorrow. This is an adapted version of the April 28 edition. Forecast the future by signing up for free.

This article was originally published on