35 Years Later, The Silence of the Lambs Remains Relevant For All The Wrong Reasons

Serial killers and glass ceilings.

In a recent expose on the FBI under Kash Patel, the New York Times reported that the lawyer-turned-right-wing-podcast-yapper had changed the bureau’s fitness test to emphasize pull-ups over sit-ups. This makes the test more difficult for women and will likely filter out female recruits, despite a lack of evidence suggesting the change was necessary. A source told the Times that the idea had come from deputy director Dan Bongino, a cop-turned-right-wing-podcast-yapper, whose justification for the decision was as follows:

“Bongino said, You can have the best female agent take down the biggest case in our history, but if on the Ring door-camera video she’s out of shape or overweight, that’s going to be the story. He was worried about whether or not they’d look good on a doorbell camera. He said it’s the way these times are.”

How it looks for a woman to solve one of the FBI’s biggest cases was the subtext of The Silence of the Lambs when it came out 35 years ago today, or at least it was as subtextual as you can get in a movie where a serial killer hucks his own semen at the heroine (happy Valentine’s Day). But at a time when all the world’s subtext has been transformed into screaming bold print, Clarice Starling’s quest to stop Buffalo Bill is haunted by the nightmares of men like Bongino and Patel. What if you need a woman to do what’s supposedly a man’s work?

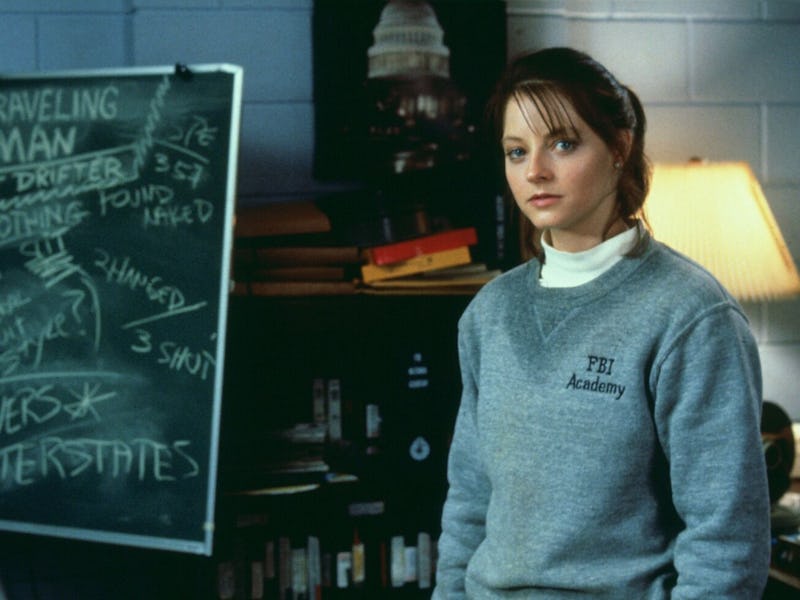

The FBI of Jonathan Demme’s film is certainly a man’s world; Jodie Foster only stands five foot one (according to the presumed experts at r/tall), and it shows. Introduced as a sweaty mess literally overcoming obstacles on an exercise course, Starling is all business from start to finish. There’s no romantic subplot, no angst about trying to balance work and family, no moment where Starling uses her feminine wiles to extract information from an ogling man. A female colleague acknowledges the importance of her case, but Starling’s not trying to shake up the agency, she just wants to be a cog in a machine that she loves.

But the men who serve that machine ogle her, hit on her, look down on her, and patronize her. She can’t seek out crucial information from dorky entomologists without getting asked out, and she can’t visit a crime scene without her mentor, Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn), downplaying her usefulness to soothe the local cops’ fragile egos. Crawford legitimately wants Starling to succeed — there’s no dowdy twist about how he’s only mentoring her to get in her pants — but he’s not above manipulating her to get psychologist-turned-jailed-cannibal Dr. Lecter’s insight on Buffalo Bill either. Later, when Crawford learns that Starling is confronting Bill alone, you have to wonder what kind of Bongino-esque PR concerns are weighing on him.

Starling stands out at the FBI...

Dr. Lecter, for his part, may conceive of himself as an enlightened effete who happens to eat people, but even his quid pro quo game with Starling sees him pepper her with lurid questions about her “sticky fumbling” in cars. Maybe he’s just trying to get under her skin — he famously taunts her with the traumatic childhood memory that provides the movie’s title — but he’s not really any more gentlemanly than the jizz-flinger. When he asks whether the relative who raised Clarice after her parents’ death was sexually abusive, he almost seems disappointed to hear no.

The full legacy of Silence’s gender politics is complicated — Buffalo Bill being an effeminate man trying to transform himself into a woman by butchering “real” women and fashioning their skin into a bodysuit has been the source of significant criticism and debate, although the movie tries to handwave the whole issue away with Lecter’s observation that Bill “isn’t a real transsexual” so much as a psychopath grasping for any identity he can get his hands on. Regardless, Bill’s predations are also a story of women being watched, judged, and hunted, whether he’s literally sizing up his victims or, in the climax seen partially through his night-vision goggles, hunting Clarice through the dark.

...but she’s still all business.

These are not new observations, but they are relevant ones now that the world’s Bonginos are ranting about the tyranny of girlbosses and the horrifying thought that it might be a slightly hefty woman who finally catches the Zodiac Killer. Every woman who dares to be competent is being watched like Starling now, and whether it’s Olympic athletes getting death threats for speaking their minds, AI being used to supercharge the harassment of women online, or women simply being shot dead in the streets, a lot of men don’t like what they see. One can only imagine how the Bonginos and Tates of the world might have reacted upon learning that a pint-sized woman single-handedly stopped a serial killer.

Thirty-five years after it cleaned up at the Oscars, The Silence of the Lambs remains best remembered for Anthony Hopkins’ chilling portrayal of Lecter. It’s certainly an effective horror film thanks to his contributions, although, if we’re being honest, Lecter’s machinations sometimes strain the boundaries of credulity. But on the more grounded procedural side, Silence remains effective because Starling has a job to do, and that’s all we need to know about her. That, alarmingly, remains its most distinctive trait.