The Paradoxical Reason 'Star Wars' Technology Retained Its Retro Aesthetic

The machines used by the Rebel Alliance make no sense from an engineering perspective-- and that's a good thing.

Star Wars has always played fast and loose with technology. This is both a cinematic weakness, and paradoxically, an advantage. More technologically savvy, genuinely futuristic canons like Star Trek invariably look dated. (The iPhone, for instance, made the Star Trek communicator feel like a phone you’d fob off on a prepubescent child.) Consciously dated from the start — the X-Wing is a World War II plane beneath its shields and S-foils, the podracer an illogical extension of American Graffiti’s drag racers. Moore’s Law holds no sway here — and thank goodness for that.

This technological incoherence manifests over and over again. There’s the strange treatment of droids and machine intelligence, the perplexing legs of AT-AT walkers where anti-gravity technology would do the trick, and glass viewing ports on giant capital ships that should, logically, be replaced with layers of armor and holograms.

But the insanity of Star Wars’ technology is part of what makes the movies work. That technologic flippancy lets it ignore real-world science rules with glee, letting the rantings of Neil deGrasse Tyson-types from the gutters of Twitter bounce off like so many deflected ion blasts. You can’t hear sound in space — so trench runs shouldn’t be pierced by the scream of twin ion engines — and thanks to aerodynamics, the iconic design of the Millennium Falcon would mean disintegration in Earthy atmospheres. But to worry about such niggles is to argue with Star Wars technology — a fool’s errand at best.

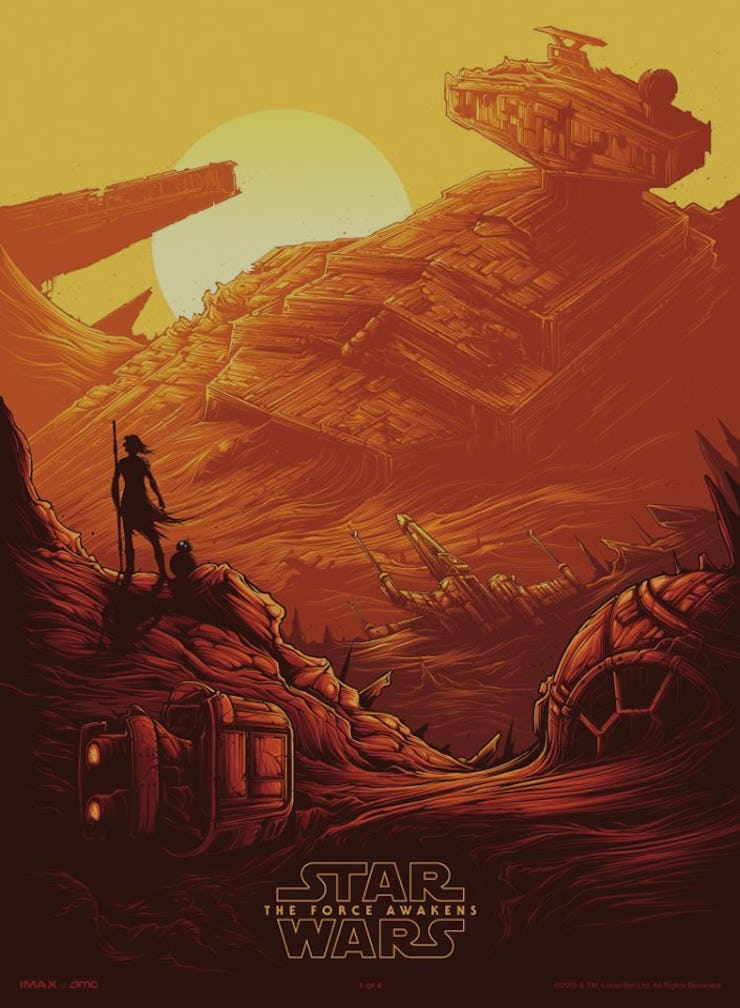

The Force Awakens feels like Star Wars, and that’s because J. J. Abrams and crew didn’t worry about — spoilers — the science of sucking a sun into a massive laser cannon, but what it would look like. Star Wars may have popularized the “used future” trope (the Falcon was and is forever a piece of junk) but it also hearkened back to space pulps where the emphasis was on the feel of tech rather than the reality of it. Abrams doesn’t tell us Kylo Ren’s crossguards are necessary because Vader’s #1 fan used a cracked khyber crystal that needs to vent dorsally. Abrams just shows us Kylo Ren’s crossguards fizzing and crackling when Ren swings the lightsaber like the broadsword it is. It looks dope and therefore is.

The incoherence marches on happily — except when the fictional universe butts up against the passage of cinematic techniques rather than the evolution of real-life tech.

Consider R2-D2. Artoo began as an advanced machine with impressive operating software; cinema evolved and gave George Lucas the power to bestow upon R2 leg-rockets. Sure, it looks cool, but it’s a problem that drills a hole through the plot two meters wide and in the shape of a thermal exhaust port. If your galaxy can have jet-powered R2 units, why not 1) strap a proton bomb to the droid, 2) send it toward the weak spot in Empire’s giant battle station, and then 3) have a party. Imperials are, after all, idiots when it comes to shooting down droids and it’s nice to imagine a Universe in which Porkins lives.

Luckily, The Force Awakens offers itself up as a retreat from the prequels’ CGI sheen. That’s a bit of fiction — there are plenty of computer-animated bits, including a frankly less believable scene where the Millennium Falcon shears out of a pine forest and into the snow — but one, on the whole, the audience could buy. Science fiction proper gets to ask whether or not spacefarers would want to spin up old Beastie Boys albums, or if sophisticated drones make ground troops obsolete a decade from now.

Star Wars’ tech aesthetic begs the director to look backward, rather than prognosticate. A few trilogies from now (if there was ever an immortal franchise, Star Wars is it) who cares if drone warfare outstrips whatever a stormtrooper could possibly do on the battlefield? Those aren’t the questions we’re looking for, and the story of Star Wars — the myths, anyway — are all the stronger for it.