Jonathan Toubin, DJ and New York Legend | JOB HACKS

The founder of New York Night Train and the famous Soul Clap Dance-Off talks music, New York, tough crowds, and how to DJ when you're deaf in one ear.

Careers rarely go according to plan. In Job Hacks, we shake down experts for the insights they cultivated on their way to the top of their field.

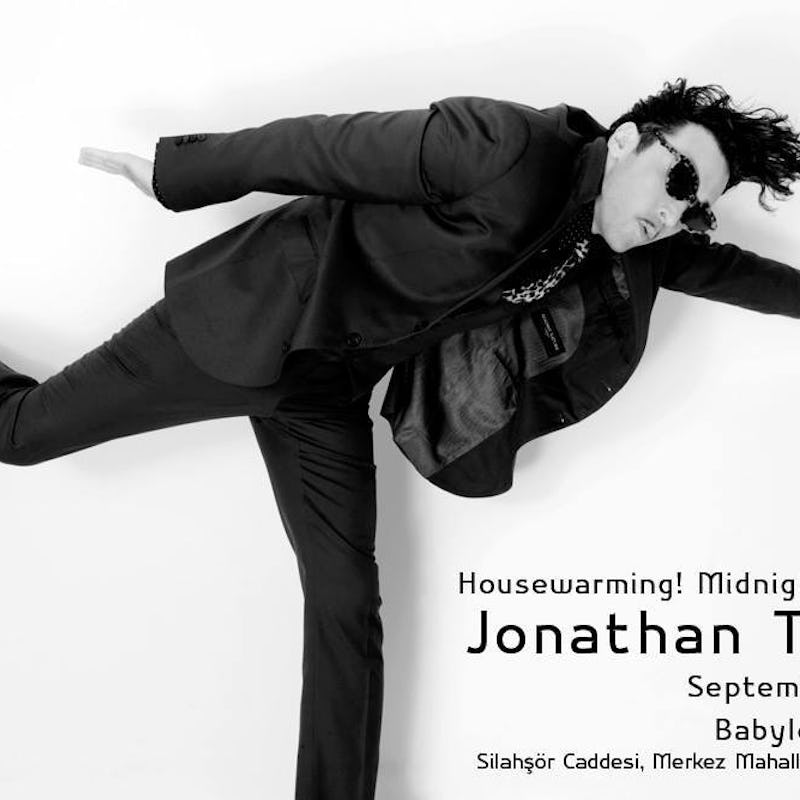

Name: Jonathan Toubin

Original Hometown: Houston, Texas

Job: Toubin is a historian, producer, musician, writer, and DJ. VICE has called him “New York’s Best DJ” and “The only DJ we actually like,” Rolling Stone has referred to him as “the most well-liked man in the soul music scene,” The New York Times has described him as “cleaner and more appreciative of American pop music history than much of the rest,” and Detroit Metro Times has called him “one of the best DJs on the planet.” Toubin has been voted Best DJ in the Village Voice reader’s choice contest and he has been featured in BBC Outlook and The Villager’s “Heavyweights of the groove”. His Soul Clap and Dance-Off is the only soul dance party to get its own dedicated night at Lincoln Center Midsummer Night Swing. He also overcame a freak accident that rendered him deaf in one ear. Visit his website or his Facebook page.

How did you get your start?

Growing up, I worked at record stores and I was always in bands. I sold two records for Kid Congo Powers, a guitarist for the Cramps and the Gun Club. He was living in New York and he had these records that needed to be put out, and I threw a record release party.

About 10 years ago, I threw a gig and one of the guys there was a DJ. He called me a couple months later and asked to put on a DJ gig for him and [Calvin Johnson](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CalvinJohnson(musician), a record label owner from Olympia, Washington. So I put on these two nights — my first ever DJ party — and I went to a bar to give them flyers. It was back in the time when you still handed people things. The bartender was like, “Why don’t you do something over here?” So I ended up coming in there every week. That ended up going so well that almost immediately, people were saying, “Oh, you DJ! Why don’t you come over here!” And before I knew it, I had five weekly residencies.

So is a large part of making it as a DJ making connections with the right people?

Maybe a little bit. Knowing people in general helps. It just depends on what kind of DJ you are. I didn’t throw a dance party until about a year into DJ-ing. But overall, it’s just that you’re providing a sound to an evening and atmosphere. With a dance party, a lot of times I would do things at places that no one would be in unless you had to party. In that case, you need to know a lot of people because they’re going to trust you to take them to someplace they’ve never been before and come out and think it’s a good time. So knowing people is helpful for getting a gig, but honestly, with the kind of thing I was doing, there wasn’t really a career for anybody back then.

How did you transition from DJ-ing casually in bars to establishing yourself with your distinctive soul sound?

It was just really hard to get people to dance, particularly to the kind of music I was playing. I was playing punk stuff and psychedelic rock and roll and garage. Some danceable music, but once you have a dance party, you realize that you have to do something else. And for someone who doesn’t really care for traditional club music — I don’t like electronic dance music, and I wasn’t the hugest disco fan then — soul was really nice because it has a beat; it’s got guitars. It’s sort of like rock and roll, but it moves.

I made this one night called Soul Clap and Dance-off in 2007. It was so I could play those records and have a chance to figure that out. It kind of lapsed into a dance contest.

Did you expect that dance contest to take off the way it did?

No, you’ve got to understand, Williamsburg wasn’t on everybody’s cultural radar back then. It was a small map of people that had been there a while. Everybody had moved out here in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. The judges in that dance contest all knew each other and all the dancers knew each other: Everybody kind of knew everybody at the very beginning of that party. It was sort of like bad theater, you know? “Who’s this distinguished judge?!” And everyone knows it’s the guy from the coffee shop.

And what about New York Night Train, your party production enterprise that’s now a heavyweight of New York City nightlife? How did that originate?

That initially started at a record label. It was also a website that mostly started to tell people about Kid Congo Powers. About 10 years ago, there was a lull in the cultural understanding that everybody has now. The internet was already around, but it just wasn’t used for that purpose as much. And it wasn’t necessarily benefitting a lot of stuff that I grew up on. So these bands that are now well-remembered — like the Cramps or the Gun Club — I don’t think they were as appreciated. I grew up with all these records; Nick Cave and the Bowers, where Kid Congo Powers’ picture would be on the back. They were important, amazing bands when I was a kid.

But no outside people came to see [Kid Congo Powers], it was just people that we all knew. A lot of these kids were getting into a lot of stuff that reminded me of these bands, but they didn’t seem to understand, and I thought it was sad. I guess it was a beginning of a historical era and a culture.

So I thought, “We have to tell people this guy’s story.” I went with him and recorded an oral history and put it online. He had old diaries from the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, he had sound files. I was still in graduate school, I was supposed to be finishing my thesis, so I was in an archival state of mind.

Then I thought, “I should do this for all of my friends’ bands.” It was a period where it seemed like a lot of young people — even in the underground — didn’t want to hear what someone who’s been around awhile was playing. So that first couple of years of the company [New York Night Train] was me putting my friend’s records out so that they could start or get back into their career.

You mentioned that you’re not into electronic dance music. Do you think the way EDM has taken over the mainstream hurts DJs who play different kinds of music? What are your thoughts on the way DJ culture has changed?

There’s been nothing better for me than electronic dance music. I’m not pooh-poohing it. I have friends who are involved with it in different levels, even down to the more corporate level. It’s one of those things where I feel like I’ve never liked stuff on the radio anyway. I’ve never bought things most people liked. So when this [EDM] came out, I thought “this is some more stuff that I don’t care for.” I don’t want to blame the internet, it’s just, you can make things that aren’t much seem like something bigger. When it comes to manipulating really young people, you can tell everybody this is what they need to do, but there’s a level and a speed.

And also when you’re living in a drug culture, it’s like, “Oh man, it’s going to be an awesome field of 80,000 people listening to stuff that they haven’t even heard of.” People go because of a cultural reason, which isn’t a bad thing at all. It’s just, I’m a 44-year-old man, and I don’t know what something like that would offer me, unless I was a music critic and needed something to write about.

Every day I go out and find this cool, older music from a different time and I find new music every day that I liked, and then your other choice is this really repetitive beat. I like soul music because it’s soulful! Every time I see a musician with a laptop and that glow of Apple, it’s like the workplace at night; it lacks that kind of human error of people playing together. If you get a record from 1962, it’s got somebody singing gospel and a drummer playing really loud because it’s supposed to make people dance. That’s dance music too, and I don’t think many people think of it in that way anymore.

What are your favorite places or ways to find new music?

I find a lot on the internet. Ebay has been the best way, if I’m looking for a record. But I travel all around. I’ve been hundreds of places the last few years. To this day, people and DJs that I like will give me a record, like, “I thought of you when I heard this.” Records come to you from all kinds of places.

And do you mind if I ask about your freak accident in which a cab drove through the wall of your Portland hotel room when you were sleeping? How did you overcome that and motivate yourself to get back into DJing?

Well there was that fear that stuff wouldn’t work in general. I can’t hear out of one of my ears now, so those adjustments were hard. But like anything, you try it and say “OK, I can do this.” To be honest, it wasn’t time to start a new career; it just seemed like the appropriate thing to do would be to go back. And I missed it. When you haven’t done what you do for a while, you have a lot of time to sit and think about it, it makes you desire any kind of activity, but particularly the one thing you do the most and that people like and that you enjoy.

What was the hardest part of DJ-ing once you couldn’t hear in one of your ears?

I do it with an open ear and a closed ear, so I can hear the sound coming from the open air and the song coming from my headphones, which is the next song I’m going to play. So with one of the ears not working, you can’t really hear the other song well. But you can start kind of feeling where that beat is. The intonation is hard to hear sometimes; I’ve been trying to get really loud monitors. I learned to work more with vibration and try to blast myself out on the ear that doesn’t have information.

Is learning to compensate for one ear the most difficult part of your job? What would you say is the hardest part?

DJing is not a hard job for anybody. Playing records — pitching and queuing them on the beat — that’s harder than on a computer, but it’s still not rocket science. The hard things about DJing are that you’re basically having a conversation with people.

If you have a hotel where somebody’s sitting there and their job is to play hip stuff and look good, I don’t think that’s a very hard job. Once you get dance parties, I feel like if it’s a mid-brow type one where someone is expected to play big hits and everyone dances, that might be easy. If someone is doing electronic or house music and people don’t know the song, it’s kind of OK because people come out for that kind of experience. They don’t really need to know the song.

But when it comes to older records, people walk up to you with a lot of specific things that they want. If you play “Twist and Shout” everybody in the room loves it. But I want to play to the kind of people who don’t want to hear “Twist and Shout” and they don’t want to hear the club hits. I’m looking for people who want something a little bit different. That’s difficult because not everyone wants that. Even if it’s a gig where people come to literally see me, it’s still constantly having to deal with mood. If you can’t make everybody go crazy out of familiarity, you have to work with psychology.

If these people aren’t feeling it, you try different things to see what’s working. You can’t keep doing the same thing all night, either. Maybe you’ll find a rhythm people can relate to, but once you catch on to that, you have to build it up and move it around. You have to surprise them; stop it and start it and put humorous devices in it; make the beats go faster and slower. Sometimes if you move it to some point you really want to be in and everyone’s going nuts and you’re like, “I’ve done it!” Then you realize, “OK, they’re getting tired now.” So then you have to move into some other place.

I guess the other problem is, when I go out of town and I’m doing a gig, all these people that come are going to come only because I’m doing that gig. If you’re in San Diego and I’m playing at the Casbah, you’re not going to go somewhere else. You’ve paid the cover, you’re going to stay there. But in New York, we move around all night.

So part of why I love it and why I hate it is because it’s five hours long. I’ll play 140 records in a night, and all of them have to be picked at the right time, the beat has to be put in there the right way. So when I’m doing all of that, I can start it out and it’s usually easy because I’ve been doing it a long time. But there will be an hour where it’s really crowded and there are people off the streets, and it’s like, “What do I play for these people?” Then the early people are going to leave because it’s crowded. Then once those people leave, it’s this weird 1 a.m. crowd. If I want to keep the place making money and the dance floor full and happening, I have to change what I do all night.

It’s like having a kitchen. You use these different spices for different things; I have to use what I have at that time to make them like it, but I can’t leave the aesthetic because that’s the root of why I’m there. So I have to change, but I have to stay the same and I have to keep my eye on it. When it’s over, it’s often exhausting. It’s a long night of different things and different worlds. If you’re good at it, no one even notices that you’re just worried the whole time.

Out of all the events that you’ve done, are there any that stand out as either one of your favorite shows you’ve played or one of the most difficult?

I tend to romanticize the ones I did when I was starting out. I can’t tell if it’s just the elation of doing something that you’re new at or time goes by and you remember things being better than they were. I remember I did my first rave, that was funny. It was in a warehouse and I was playing lesser known James Brown records and the Stooges and all the stuff you wouldn’t have at a rave and people went nuts. I remember that really well because I thought everyone was going to hate it because people hadn’t heard a human voice in hours. I played a gig in the park this year, which was cool. It was for free in Madison Square Park for the city. That was cool because it’s not in the middle of the night, it’s not exclusive due to price, it’s free, and it was really great for me to see people that were 6 years old and 80 years old dancing. I love 20-somethings and it’s what I’m used to, but it was cool to see little kids and old people in the mix.

What advice would you give to a young DJ who is just starting out?

Don’t do it! No, I would say try to be true to yourself and what you believe. Particularly, try not to do anything that you can’t stomach, even if they’re paying you.

Have you been pressured to do anything you didn’t want to do?

All the time. People think DJs are like a juke box. They’ll walk up to you and say “This is what I want to hear.” Or sometimes they hire you at an event because you’re a known name, but they want you to play whatever they want. I know this is a whole other issue, but it has a lot to do with the suburbanization of the city. In the past, you’d want to hear someone who’s known for doing what they do. These days, I think because the aesthetic of the city, everyone wants to hear the same Top 40 that people hear out there in the city, and it makes people uncomfortable that there’s stuff they don’t know. I’m playing what I think is good-time party music, and it makes people on one end of culture almost violently mad. Recently, I was at a hotel pool party in Austin, at a sold out $30 per person event, and a girl with a $20 drink didn’t like the music. She poured her whole drink on the record, the mixer, everything! Just because she didn’t like the music.

How did you deal with that?

I just tried to have some decorum. It was just so odd for me to have somebody come up and show me that level of, “I want to push my will upon you.” It’s getting to a point where people who want something different — culturally, I feel like they’re losing the battle. All the hipster hate of the early 2000s — a lot of people that would just be called bohemian or counter culture — now people have to be like, “Oh, I watch football too!” It would be totally fine to be like, “Oh, did the Super Bowl happen?” Or like me: I can’t name a Beyoncé song. I’m sure she’s great; I just wouldn’t be into that kind of music. It’s fine that all of my friends are — but I feel like the tables have turned. Instead of squares feeling guilty about what’s going on, now you’re having reasonably hip people feeling guilty about being reasonably hip. But even with someone like me, I’ve had a pretty decent level of success doing what I do, and it’s surprisingly to me that the more success I achieve on that level, the more people that I have to deal with that are not just upset, but are livid that they’re hearing this music. It’s really surprising. Like, I could go somewhere else. You don’t go to a restaurant and demand your Subway sandwich. I guess more people are into Subway now.

What are you most excited about, moving forward?

Well in the immediate future, I’m going to Australia for a little week tour. That’s exciting. I guess in the long term, I’m in a weird period. I’m making another record right now. I just took a break from Soul Clap after nine or eight years. I’m going to take a break from a lot of things that I do and try to reformulate what I do.

Geographically in New York, the map has changed so much since I started. Ten years ago it was so quaint. It was this ancient time where a lot of people hadn’t even been to Bushwick. I want to reevaluate what I’ve been doing; change some of the things I don’t feel like are what I intended or what I believe. I hadn’t played music in forever and last week, I did this Velvet Underground cover at the last minute at a Halloween party. I was Lou Reed and I played guitar and it got me interested for the first time since like high school. It got me thinking about New York and why I came here and the things I was looking for and the kind of world I was interested in.

In a lot of ways, stuff like that makes you question some of the things you do that you don’t believe in as much. Your heroes that never really gave in and always did the opposite of what they were supposed to do. Right now those are the people having a big effect on my brain. I want to change a lot of stuff; I hope to create something for people like me. I’ve always liked everybody and tried to make everything non exclusionary and have everyone involved. I always hoped for a positive, friendly, interesting thing and not an angry culture war with all the people I’m not trying to appeal to anyway.