Gaspar Noé's 'Love' Says a Lot Less About Sex and Sexuality Than It Thinks It Does

The notorious French director's explicit epic seems seems to aim for everything and nothing.

Perhaps you’ve heard some of the noise surrounding Enter the Void director and provocateur Gaspar Noé’s newest film, Love. The word about the movie has been out for a while: It was shown at Cannes in May, where it was relegated to an out-of-competition midnight screening. Nonetheless, the word about the cum shooting at the camera and the ten-minute-long sex scenes got out fast.

It is no exaggeration: The central action in Noé’s Paris-centric film is unsimulated sex — between ten and fifteen scenes of it, to be exact. The film cold-opens on uncut mutual masturbation, to make this instantly clear and goad any potential walk-outs to do their worst. There are some scenes in Love in which even the lead-up has the distinct feeling and execution of a porn setup: An inquisitive couple lures a next-door neighbor into a threesome, two relative strangers get together while their significant others are out of town, a transvestite persuades a straight male to experiment, and a group explores an all-ages sex club for the first time. Unfortunately, the film does not clarify this implication, or channel them towards any greater purpose.

Noé’s sex scenes are plateaus that punctuate a story — non-linear in realization, but very traditional in the details — which takes place mostly in the memories of the film’s protagonist. This is the aspiring filmmaker and American expat Murphy, played by the unknown Karl Glusman. The storytelling — fragmented, full of voiceovers of his thoughts, drug-addled — is similar to that of Noé’s Tokyo post-mortem vision quest Enter the Void, though the through-the-eyes perspective is abandoned here.

Though Noé claims Murphy is not intended as a stand-in for himself, he does pontificate a good amount about filmmaking in the second half of the film, in a way that it is unambiguously meta-filmic. Murphy rants to others about wanting to make movies that are lush and “sentimental” when it comes to sex, and that highlight the best type of sex, which happens when one is in “love.” There is also a cringe-inducing line about wanting to make movies with “blood and sperm.”

In Love, sex becomes the central way that the dominant relationship in the film — between Murphy and his art student ex-girlfriend Electra (yes, intentional resonance with the Greek mythological/Freudian “Elektra”) — is characterized. It is not kept largely off-screen, or reserved for cathartic moments (i.e. “the big sex scene”). It is the day-to-day for Murphy and Electra — the mortar of their relationship, but also a source of fuel. This matter-of-fact approach is unconventional in narrative film, but also not unheard of: Higher-profile art films like Last Tango in Paris, and movies by directors Michael Haneke, Peter Greenaway, and Kenneth Anger have touched on these ideas; most recently, Blue is the Warmest Color offered a refreshing frankness about sexuality that creates resonances with Noé’s approach (He has expressed his reverence for the film).

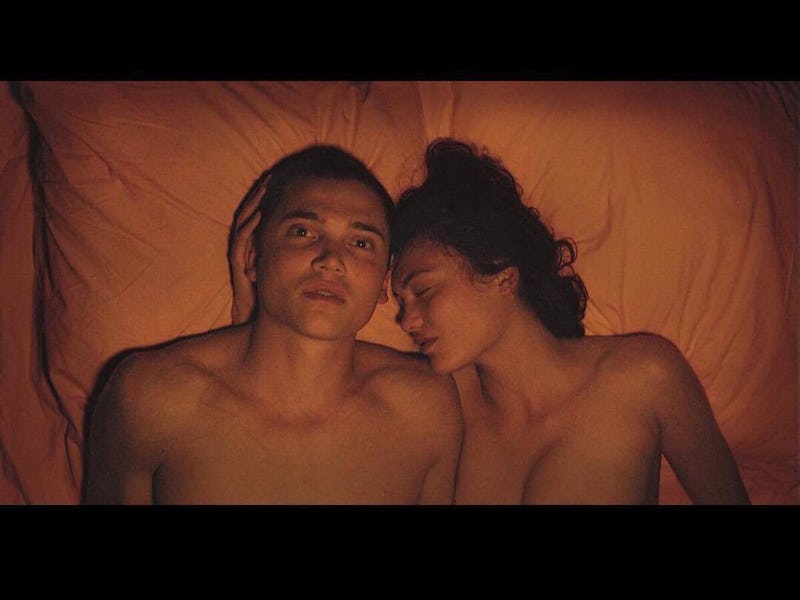

Murphy and Electra in "Love"

Unfortunately, Noé’s execution doesn’t advance this rich tradition much. Unlike in Blue, Love’s sex doesn’t help us know these characters better, because in the film as a whole, characters feel decidedly beside the point. A big part of the problem is that Noé’s filmmaking process involves amateur or non-actors improvising their dialogue, and it almost seems that he hoped clear characters would result from this interaction.

But they don’t materialize — unfortunately, the female characters, particularly, get short shrift. The omnipresent Murphy’s inner monologue is suffocating and often unintentionally hilarious: “A dick has only one purpose: to fuck, and I fucked everything up.” The extemporaneousness often feels stagey and awkward as much as actually intimate. It is mainly in the sex scenes where Noé seems to be getting close to accessing something deeper, but it’s hard to relate it to the rest of the film.

It is this lack of build that is Love’s biggest issue. Nothing feels connected enough to what comes before and after it; no powerful and comprehensive picture comes together. You feel Love’s length painfully as a result. Over time the power of stronger sequences in it (the moment of the breakup, the scenes with Murphy’s new girlfriend, charmingly banal conversations between Murphy and Electra) are cancelled out by three times as many forced and half-baked ideas, and the undue attention put on Murphy’s unconvincing feelings of grief and loss.

If Noé is seeking to postulate a future for sex in film, he doesn’t lay out a convincing business model here. Love simply feels like a one-noted mission statement carried out unimaginatively.