Lasers Can Tell Us More About Fossils Than Before

A new technique illuminates patterns in fossils that have never been seen before.

Laser light can illuminate differences in fossils paleontologists weren’t able to see previously, giving future scientists more clues to how people lived in the past. Including what sort of jewelry they wore.

This week Seattle-based researcher Tom Kaye expanded on his laser study by answering questions during a Reddit AMA session about the technology — plus questions about his favorite dinosaur and his former life as a paintball mogul.

Inverse talked to Kaye after the event to learn about his recent innovation in lasers and paleontology. “The technology has advanced to the point where it has opened up new vistas that we can utilize,” he says.

A mid-Holocene-aged skeleton of a small girl preserved wearing an arm bracelet, found in Gobero, Niger.

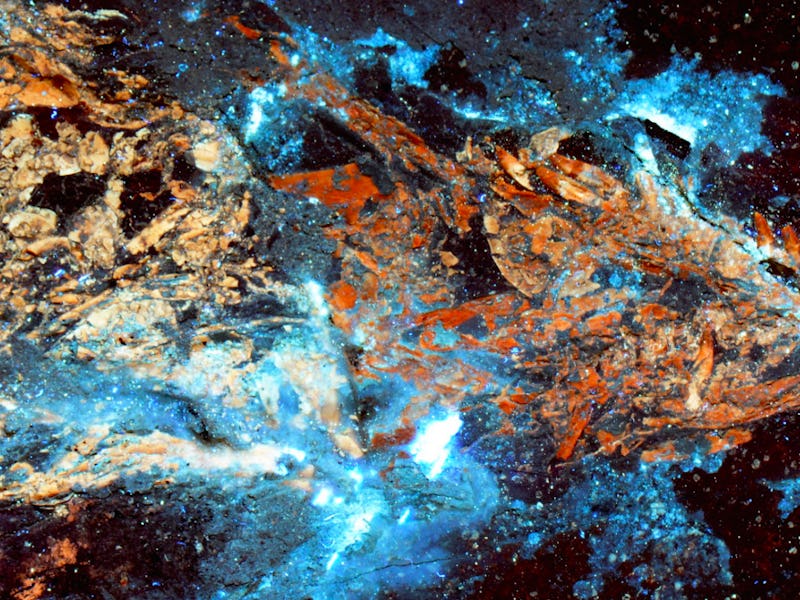

In one case in his study, Kaye investigated a bracelet on a 6,000-year-old skeleton of a young girl. It couldn’t be removed from her arm, so he used laser-stimulated fluorescence to take pictures of it.

A pattern of cracks emerged that couldn’t have been seen under regular light. “It turns out this cracking pattern was identical to a fossilized hippo tooth we had from the same area,” says Kaye. This was one of the clues that led the paleontologists to determine that the bracelet was made of hippo ivory.

Kaye recently published a paper in PLOS ONE, an anything-goes-as-long-as-its-proven-by-science journal, on stimulating fluorescence in fossils using lasers. It describes five cases where his technique revealed aspects of a fossil that could not be seen under normal light, including clues that led to that ivory bracelet.

The technique works by shining a high-powered laser onto a rock or mineral. When a photon enters an atom that it strikes, it interacts with it and is released at a longer wavelength. By using a long exposure on a camera that has a filter to block out the original color of the laser, you can capture all of those other colors that are fluoresced back from the surface.

A fossilized bracelet imaged with normal light and laser fluorescence.

Kaye hopes his process will be used to investigate preserved remnants of soft tissues around fossils that, until recent years, paleontologists didn’t know were there.

It used to be that researchers would carve out a fossil right to the bone, assuming that it was incased only in dirt, he says. “We now know that when you do this, you’re carving away a lot of the halos and a lot of soft tissue preservation that you wouldn’t see normally, but may show up under fluorescence.

“Over the past decade there’s been a lot of side investigations into what else is preserved besides the bone, and it looks like there’s a lot more information there to be had. So it’s changing the face of paleontology.”

An illustration of Anchiornis, a small, feathered dinosaur.

Kaye says his favorite dinosaur is the Anchiornis, a recently described specimen found in China.

The discovery of this dinosaur has been one of the most significant paleontology finds, because researchers are seeing evidence of soft-tissue preservation in a way that hasn’t been seen before. Some research suggests we can even know the color of the animals, thanks to preserved evidence of melanosomes, or pigment cells, in the fossils.

Kaye recently traveled to China to look at hundreds of samples of this sort of feathered beast. “We were delighted to find that a few of the hundreds of specimens we looked at were spectacularly preserved and had anatomical details that we never expected to see, until they came out using the laser under fluorescence.”

He expects to publish the findings in an upcoming paper.

Kaye

Next week Kaye will be at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology’s annual meeting, where he hopes his laser fluorescence technique will make a splash. With a basic equipment set up costing just $500, he expects the technology could very soon become standard practice in fossil investigations.

“If we find enough of these impressions and things that light up under the laser, it may change the way we look at these fossils.”