Dylan Goes Electric: Rock's Greatest Tall Tale, 50 Years Later

How we remember Dylan's Newport Folk Festival debacle.

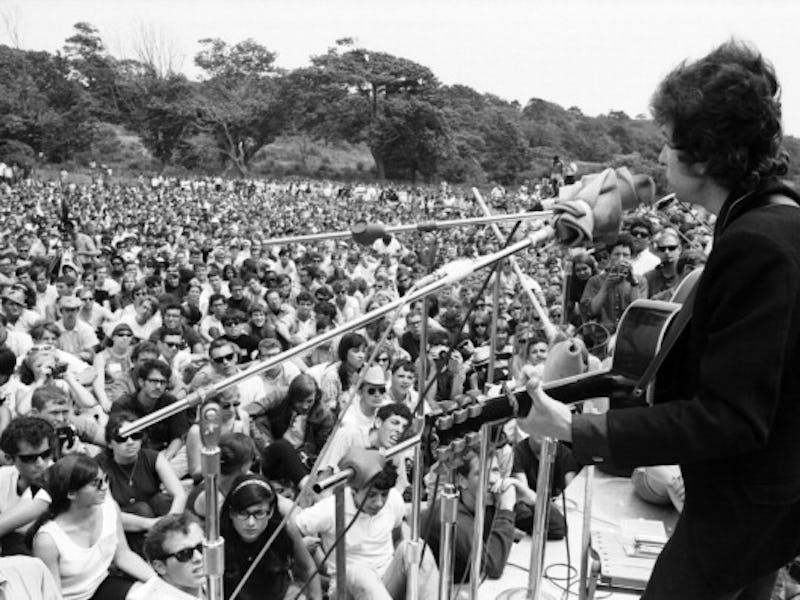

This weekend marks the 50th anniversary of Bob Dylan’s infamous electric set at the Newport Folk Festival, the first public performance Dylan did with a rock band. It’s a cultural moment around which the history of popular music has been constructed — the moment Dylan broke with his “folk” roots and revolutionized popular music. The show is the takeoff point for a new book by one of pop music’s finest scholars and canon-busters, Elijah Wald — Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties.

The accepted narrative surrounding the event is more-than-a-bit apocryphal. There are many factors to consider when speculating about why, exactly, the set incited boos, as well as the various reactions to it from notable figures in attendance, the context in which the audience viewed it, and Dylan’s own attitude toward the performance.

As the story goes, the crowd at Newport was shocked when Dylan mounted the stage with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band — plus Blood, Sweat and Tears’ Al Kooper on organ — and played a set of searing electric music. Some remember trash being thrown, and Dylan being booed off stage. Folk-revival patron saint Pete Seeger is believed to have been so angered by the racket that he tried to cut the power.

But this simplistic, wholesale view of the reaction doesn’t make complete sense. Dylan’s first foray into electric music — the Bringing It All Back Home album — had been out for several months, and his now iconic song “Like a Rolling Stone” had debuted to much fanfare a few days earlier. The crowd was doubtless prepared for Dylan to try out some of this material; it was not the shot heard around the world.

Seeger, himself, has remained adamant that his reaction to the music was not a hatred of the idea of electric music coming to the festival. He was prompted to make a remark about wanting to “cut the cord” because of the poor quality of the mix. He was particularly angry that Dylan’s vocals were so buried and unintelligible — understandable since Dylan’s unhinged, psychedelic verses were considered the main sticking point of his new music, not merely din and rhythm.

Many people remember the sound being terrible, and the performance itself being sloppy, especially at the start. The band had only had one night of rehearsal. The bassist, Jerome Arnold, taped chords to his bass; there was essentially no sound check. Al Kooper recalls the group getting off- beat on “Maggie’s Farm,” the opener; you can hear this in the recording of the show. They ran through only three songs before leaving the stage without a word. The MC — Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul and Mary — returned to wrap things up. The recording evidences a very mixed reaction, though deafeningly loud and dominated by some loud boos. It’s easy to hear how this would have been mostly a reaction to the poor mix, the brevity of the set, and Dylan’s brusqueness. Kooper even remembers hearing “more!” rather than “boo.”

Another piece of misinformation is the idea that Dylan’s set was the first time electric music had ever been played at Newport and was anathema to the folk scene as a whole. The Butterfield Band had performed the previous day in their own right, and classic blues acts such as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf — veterans of the festival — had already begun to perform in electric bands. The change was in the wind; as Dylan put it in a 1985 interview, “I had a hit [electric] record out, so I don’t know how people expected me to do anything different.”

It’s also easy to forget that Dylan did a heartfelt, acoustic encore of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” which mollified the crowd – he’d also performed some pre-Bringing It All Back Home acoustic songs at a workshop the previous night. The decision to play with the Butterfield Band had been made spontaneously at the festival; it was not a concerted effort to overthrow the establishment.

Looked at from almost any other angle than being the beginning of the “social drama” Dylan created, as rock critic Greil Marcus put it in his Dylan treatise Invisible Republic, or that it was a moment that “changed the rules of folk music,” the Newport set comes off as something of an aberration. But though it was not — in practice — a great performance, it has snowballed in significance in retelling. Though the negative response was not as vociferous as it would be on his subsequent tours with the Hawks (who would eventually become The Band in their own right), it’s regarded as Dylan’s most controversial performance.