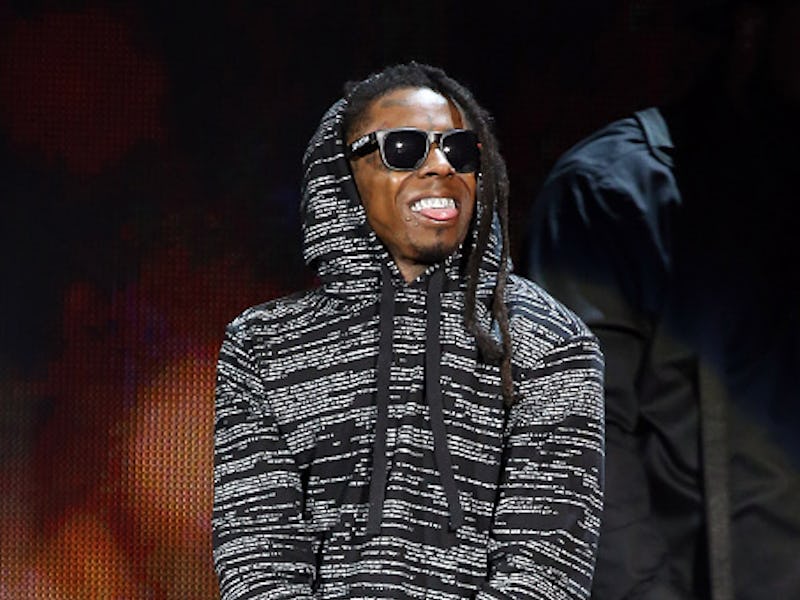

Label-less and Anonymous: Lil Wayne's 'FWA' Misses the Mark

The failure of Lil Wayne’s 'Free Weezy Album'

The last time you heard a Lil Wayne song you were sure you liked may have been a half-decade ago; then, the New Orleans rapper was rap’s biggest superstar. This is a reductive view, to be sure, but today, one mostly hears Weezy eking out space on other people’s Top 40 singles — for instance, Nicki’s “Only” and before that, radio mammoth “Loyal,” a knockoff DJ Mustard production helmed by Chris Brown. Until this January’s Sorry for the Wait 2 mixtape, it had been over a year since we’d heard a new Wayne full-length (unusually long for him). But the album we were Waiting on — the supposed double-disc Tha Carter V — is not the project we got, and it still hasn’t surfaced. Wayne is in a public feud with his former mentor, surrogate “daddy,” and label head Birdman née Baby over the latter’s refusal to release the album, which Wayne had reportedly been working on for several years. The action culminated in the announcement of a 51 million dollar lawsuit, and a public feud with Birdman’s new protégé (and one of Atlanta’s biggest rising hip-hop stars) Young Thug, who attempted to name his most recent full-length Tha Carter 6.

Sorry for the Wait 2 was a broadly disappointing project, featuring Wayne wiping out on the beats for other people’s already-played-out hits. Like 2013’s Dedication 5, it felt like an attempt to recapture the feeling of his most beloved mixtape work in the mid-2000s. His newest Tidal-released album, FWA (shorthand for the Free Weezy Album), on the other hand, uses all-original beats and lives stylistically more in the present day, but it’s no less of a lemon. In fact, a whole new problem is introduced when Wayne is picking from fresh production, rather than jacking them: He has, largely, poor taste. Generally, the rapper landing a great beat feels like a fortuitous coincidence rather than an astute choice. Particularly ill-advised on FWA are the head-scratcher of a James Brown interpolation “I Feel Good,” the As Animals-sampling, rap-rock-trap “He’s Dead” and “Thinkin Bout You,” which boasts a rinky-tink, sub-ringtone beat from frequent Wayne producer Infamous.

The problems are compounded by the fact that Wayne remains intent on attacking or, one might say, conquering the instrumentals rather than interacting with them. There’s very little negative space on this album, and sometimes it feels like Wayne could be making exactly the same moves on almost any beat. And of course, those particular moves are often worse than pale imitations of his former self (see Tha Carter IV and I Am Not a Human Being 2); here, he sometimes seems to be basking in anonymity. Wayne’s voice — formerly one of the most expressive and varied in rap — sounds flat, dynamicless and processed. The “personality” in his rapping is largely borrowed, full of attempts at the self-reflective emotional catharsis of his former lieutenant Drake (“London Roads”) and the warbling vacillation between chest and high voice and trap-styled fast flows of his new-found rival Young Thug (“I’m That N—gga”). The “for my baby”-based opening of “Psycho” sounds like a revamp of the chorus of Fetty Wap’s recent smash “Trap Queen.” There are moments here when you forget you are listening to Lil Wayne at all; on “Pull Up,” one of the album’s better tracks, he trades quick phrases with recent Young Money signee Euro to the extent that you lose track of who is who. On “Living Right,” he is somehow shown up by Wiz Khalifa.

Where there is definitive Weezy-and-only-Weezy, it is on the cusp of self-parody. Most chuckle-inducing lines (“Woo, this that shit you didn’t want me on/ My weed louder than underarms and car alarms”) feel cringe-worthy the second time around. Much of the rest of what he says is unambiguously embarrassing (like, say, this other armpit line: “Fuck your degree, this murder in the first degree/ I got that tech under my arm like Right Guard, sure, Degree”) or non-descript. Even the best tracks — see stuttering last-quarter anthems like “Post-Bail Ballin’” and “White Girl” — are foiled by cloying choruses. Nonetheless, somehow, this weak album is probably Wayne’s best work since 2010’s No Ceilings. At least it sounds like it was made in the present day and demonstrates the rapper attempting to interact with and give back to the larger hip-hop climate, if he’s only capable of reflecting it back on itself.