California Drives Home the Uber Employment Problem

A labor ruling that the company treated at least one driver as an employee could change everything.

With Uber raising capital on its way to a $50 billion valuation and an inevitable public stock offering, the last thing the company wanted was to have its cost structure disrupted by the California Labor Commission. And now, thanks to an Uber appeal we know that is precisely what happened in March.

Uber is fighting a March ruling from the commission ordering the company to reimburse former driver Barbara Ann Berwick $4,152.20 for expenses and other costs she incurred during her time ferrying Californians. Berwick worked as a driver for just over two months last year. While Uber argued Berwick was an independent contractor, a popular and less degrading term than Task Monkey, the commission found they were treating her, and most of their full time drivers, more like employees and therefore they (the quasi-employees) were entitled to things like workers comp and unemployment insurance.

“Defendants hold themselves out as nothing more than a neutral technological platform, designed simply to enable drivers and passengers to transact the business of transportation,” the commission wrote. “The reality, however, is that defendants are involved in every aspect of the operation.”

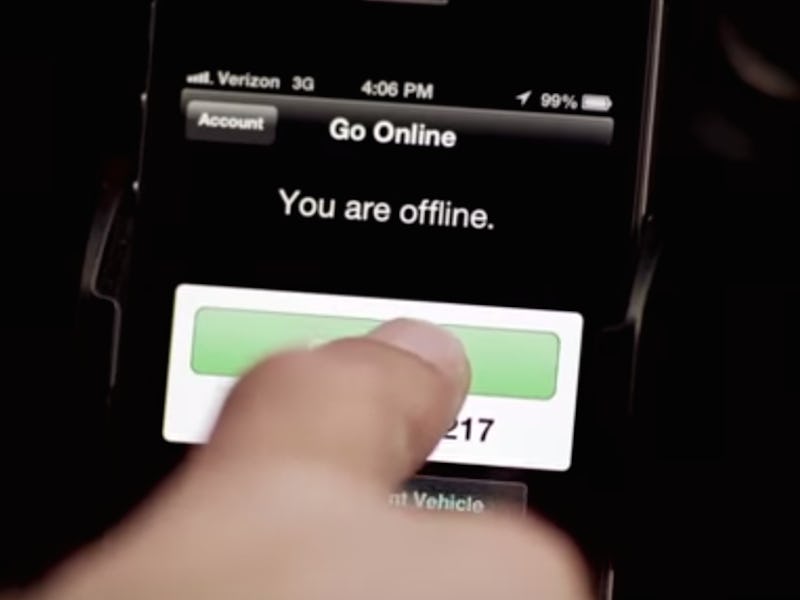

A major consideration in the ruling was how little Uber leaves drivers to their own devices. The company controls the tools they use, monitors approval ratings, and cuts them out of the system if their rating drops under 4.6 stars.

Uber’s enormously successful business model relies on treating these drivers as independent contractors, a designation that’s done nothing to diminish applicants. It’s a common company boast that the pool of drivers has doubled every six months with no sign they’ll be riding the brake any time soon. It’s a near certainty December reports pegging the number of active drivers at over 160,000 would seem quaint compared to today’s rolls. Many are pulling in more than their taxi driving cousins, with an average profit of $30 an hour in New York, $17 in L.A., and $23 in San Francisco. That’s not terrible on the surface, but when you start cutting it down with taxes, licensing fees, Uber’s commission, parking fees, gas, maintenance, car insurance, and all the other hidden costs on their backs as “independent contractors,” a New York driver’s take home is closer to $12 per hour.

Once the ruling went public, Uber scrambled to cut off an uprising, telling drivers that the decision only applied to Berwick. That’s likely correct — for now. But all hell is going to break lose if that doesn’t stay correct. Uber could get effectively booted from California or see its overheard go from minimal to absolutely massive. The ball is in the judiciary’s court, but you can bet the company’s executives are bracing themselves for another appeal or action to save what has been — for them anyway — a very profitable business model.