Neill Blomkamp Wants to Reimagine Hollywood. He Just Needs Money

The 'District 9' director explains his master plan, and the challenges he faces.

When Neill Blomkamp burst onto the scene in 2009 with his Oscar-nominated, future-apartheid satire District 9, it seemed to many viewers like he had arrived fully formed, a wunderkind who had delivered a near-perfect debut feature. But he had been working for a decade before that, first as a visual effects animator and then on commercials and his own short films, including the acclaimed Alive in Joburg, which set the tone for District 9.

He was embraced by the studio system, which financed and produced his next two feature films; 2013’s Elysium was a moderate success, 2015’s Chappie less so. And after spending years developing a sequel to Alien at Fox that got cast aside for Ridley Scott’s latest outing, the 37-year-old filmmaker is returning to his experimental roots with Oats Studios. Right now, Oats is a fledgling indie house through which he can experiment with new ideas and release short films directly to fans, with the idea that some day they could get made into full-fledged features.

“The goal was that we needed to make some form of a strange, independent studio that can put ideas out into the web, and if one, or two, or ten, or twenty percent of the ideas are successful with the online audience, we can turn those into proper feature films, recoup enough money to make Volume 2, and keep going forward,” Blomkamp tells Inverse. “And you always have an incubator, this kind of lab of ideas that you would always be putting out, which in and of itself would be really creative and really rewarding.”

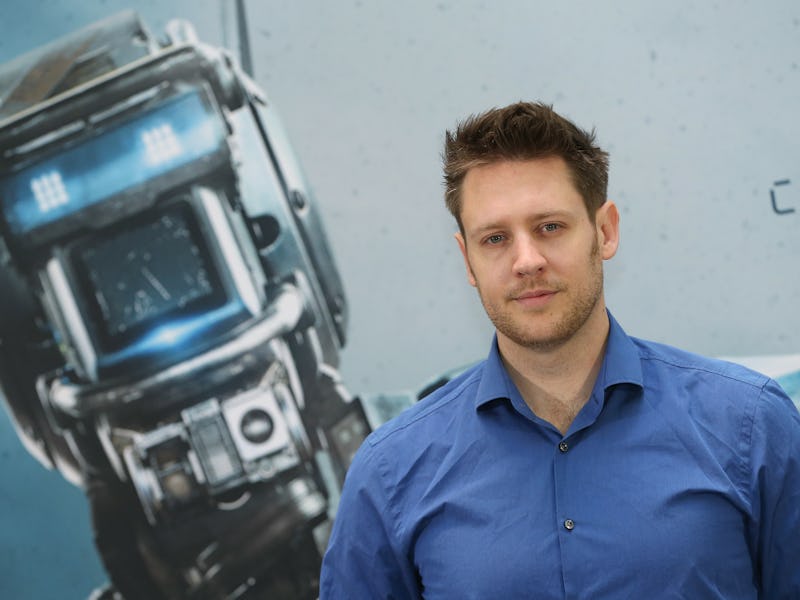

WESTWOOD, CA - AUGUST 07: Actors Matt Damon, Jodie Foster, and director Neill Blomkamp attend the premiere of TriStar Pictures' 'Elysium' at Regency Village Theatre on August 7, 2013, in Westwood, California. (Photo by Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

Much of Oats follows that initial plan, but there is a deeper and more interactive element that he had not at first anticipated. Through its message board and the Steam platform, the studio offers many of the assets featured in its short films to fans and visual effects hobbyists at home, so they can remix and repurpose the files for their own films or other tactile projects; a forum allows them to communicate and troubleshoot with the fans working on their own VFX work. And the options the studio will have to distribute its finished full-length products has changed over time, as well.

“Now, if we did make full-size films out of any one of the shorts, they could be in theaters, and it would be cool for them to be in theaters, but they don’t have to be,” Blomkamp adds. “The whole system has changed so much.”

So far, Oats has released three well-produced, VFX-heavy shorts that clock in at about 20 minutes each, as well as a funny web series about a corny infomercial chef set in the 1990s. That marks the entirety of what he calls Volume 1, which came at the cost of “millions and millions of dollars” — as he’s discovered, there’s a high cost to making your dreams come true. Blomkamp further discussed his vision, and the hard economic challenges he’s facing to achieve it, in the interview below.

Did you go around pitching this studio to deep-pocketed financiers? It can’t be easy to get people on board with an experiment.

No, and luckily I haven’t had to do that yet. By the time Volume 1 is done, we will essentially have spent all of the available cash. So, in order to do Volume 2, you’re faced with a situation where it’s either, do you actively go and ask for finance from someone? Or, and this is more appealing, seeing whether you can extract it directly from the audience if they really do believe what you’re trying to do.

You can also grow. We can ask the audience to fund a lower-budget idea that we can play theatrically, that can pay us enough to make Volume 2, and then the next film that you do can be bigger than that one. Maybe we can do a District 9-sized film. And then you scale up from there.

What we have built, at the moment, is the infrastructure within the studio to be able to execute that film. Like right now, with no question we could execute District 9. The way more complex question is how to economically fuel that in a relationship that is like 1:1 with your audience. That’s, like, way more difficult.

You’ve offered assets on Steam — do you want people to contribute to the films, like Joseph Gordon-Levitt does with albums made through his company, HitRecord?

No. I’m not looking for that kind of relationship. This is how I think of it: Traditional Hollywood tends to take existing IP, and then they shackle it up. So, if you were a 19-year-old director, or were a film school student and said, “This is my cool film that I made with Spider-Man,” there’s a possibility that that could get pulled offline. It could just get shut down. There could be copyright infringement issues. It could be anything, right?

What I want to do it like the opposite of that. If I own Spider-Man, I will open it up to the whole planet, and I’d put on like competitions to see who had the best Spider-Man short. If someone designed T-shirts and merchandise that had the River God from Firebase all over it, I love that idea. If you try to do that with Batman, you’d be in trouble.

How big is your staff of people who will work on the movies?

Well, full time in the building is somewhere between 30 and 40 people. That’s basically like the company, I guess. If you go outside to go and shoot, you could be at 80 to 160 crew members.

Are the staffers all working on the same projects, or do you have more things in development? How fast do you ideate things?

The much bigger issue right now is the economics of the whole thing. This, so far, has been like a philanthropic mission, essentially. Which is insane, but that’s how it’s been. So, solving how to make Volume 2 is what is taking up my brain right now, where a lot of scripts and ideas for the content of Volume 2 already exist. And there were certain pieces that were too expensive to make for Volume 1 that are just really compelling.

Funny or Die is an engine for original comedy that also does a lot of commercials and advertorial work. Do you imagine that Oats would be involved in that if it helps finance future creative projects?

I don’t want it to be that. I really don’t like the idea of advertising. I think it’s more a case of, if the audience likes what you’re making, and they want to see more of it, then we just need to figure out how to give them the ability to fund us to make more of it in the easiest way possible. That’s what I want to do.

And the question is, do we front the money to make a feature film that they buy traditionally, that they know fuels Volume 2, or do we offer directly to fuel Volume 2? Those questions are the questions, those strategic questions where advertising is just another layer of noise between the content creator and the audience watching the stuff.

What from the studio system do you want to avoid recreating?

It’s not really a case of bashing that system and rebelling against it. It’s more a case of me trying to build a system where I feel I’m being as creative as I can be, and I feel like the decisions and the discussions that you have with film studios tend to be pre-guessing what the audience is going to think. That’s really all you’re doing, right?

It’s like, “We shouldn’t make this. Why? Because we don’t think it’ll do well, unless you put this actor in.” Okay, if we put this giant actor in, then why would it do better? “Because they recognize him.” Yeah, but you don’t know that. So maybe let’s just test it, you know? So instead of second-guessing the audience, I just want to hear from them directly, and making pieces that are smaller and less expensive and just seeing what they say lets us know where we stand.

So it’s not really like I’m trying to break free of the system, it’s more like I feel creatively happier doing it this way.

Right. It’s a better alternative.

But there’s negatives that come with that. I mean, all of the pressure is on us. Financial pressure, everything. Just the logistics of setting up, like how to even do a shoot is entirely on us inside the studio.

The other negative is, like a $100 million in a studio film, you can really show the audience something really interesting and massive; you can take them on a real ride. That’s not possible for us. So the negatives are that the stories are smaller, and the scope is smaller. But that comes with no restrictions as well. That’s an upside that is greater to me than a $100 million canvas.

One of Oats' recent creations — not a practical effect.

It is still expensive in terms of the talent required to make visual effects, but at least rendering time has gotten faster, and big special effects are a bit cheaper now, right? Does that even the playing field a bit?

I don’t know if it’s that much cheaper. I always wait for that to happen, and it never seems to actually happen. It’s interesting because there’s a lot of, there’s laws that get applied in computer graphics, where they always say, it’s kind of like, it’s a version of Moore’s law, where the more complex the calculations become, like your processors become quicker, the user will just place more requests on the processor.

Is part of the incentive here getting to create and keep your own IP, instead of sinking years into something and then not getting to make it, a la Alien?

Yeah, and also you can’t control the marketing, as well. How the audience is going to be introduced to the film that you’re trying to make to show to them. That’s also a big deal. Yeah, I think just being in a place where you’re in control of the concepts that you’ve made is where we want to be here. That factors in for sure.

Were you frustrated in the past at the marketing of your movies?

[Laughing] Umm … maybe.