Chicago's Hype-Free 'Automate' Will Be CES for Smart People

The future of manufacturing and the American workforce starts here.

We’re calling it now: The most important electronics show of 2017 won’t get the recognition it deserves. Removed by 1,500 miles and roughly $150 million in marketing budgets from the technicolor arcade of the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Nevada, the Automate Show in Chicago, Illinois is a staid, business-to-business affair — with the potential to help reshape the American economy. The biggest industrial robotics show in North America, Automate is keeping pace with automation as a manufacturing trend. This year, it will be 30 percent larger than it was last year and it will host 300 exhibitors and 20,000 attendees. If manufacturing workers are worried about their jobs, they should be focused on the April event, which will showcase the latest in automated coworkers and the future of tools. That’s less than a sixth of CES’s human haul, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a more significant number.

“CES is cool, but it’s about the stuff none of us really need, just sort of wish we had,” says Bob Doyle, the Director of Communications at A3, which puts on Automate. “In a lot of ways, it’s like the big runway fashion shows. How many of us will really wear that stuff? Not many. The impact comes over the course of the year as the possibilities and themes are slowly implemented for the real world.”

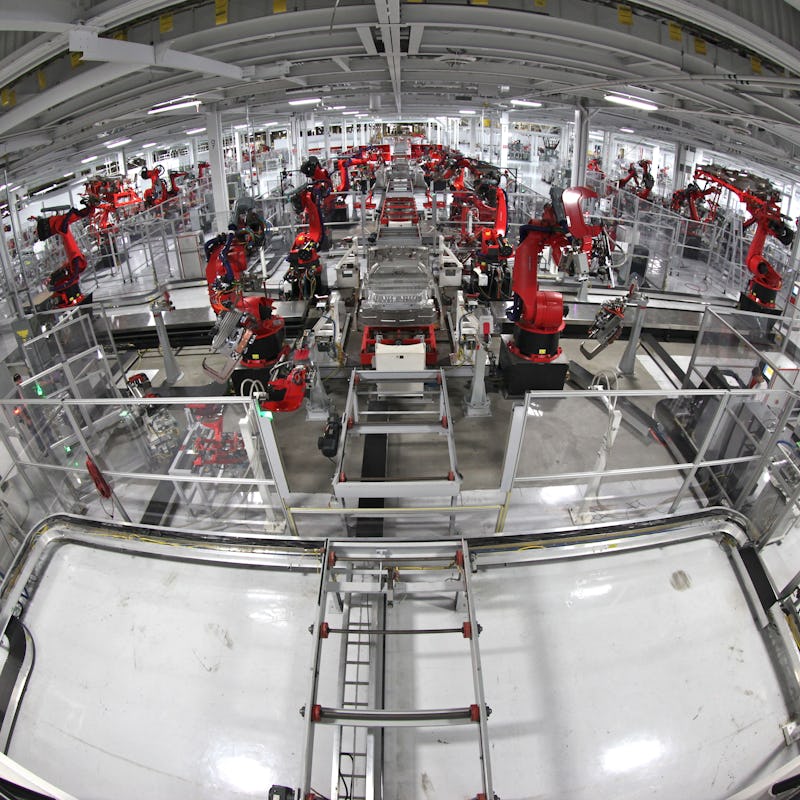

There’s no question that automation will play an increasingly large role in the global economy over the next decade. While robotic workers have been a mainstay of production lines in many heavy industries, advancements in the processing power, artificial vision, and dexterity of workplace robots have made automated systems feasible in a huge variety of fields. Both multinational corporations and smaller shops have noticed.

“Small companies used to feel that automation was too costly and too complicated to implement,” says Jeff Burnstein, president of A3. “They felt it wasn’t something for them, it was only something for companies like General Motors.”

For vendors, Automate is the place to change that thinking.

“Automate is the Industrial robot show for North America,” says Nigel Smith, founder and CEO of Toshiba Machines Robotics. “It’s a must go to show for the manufacturer for the key distributor to show off the new technologies that we are launching and developing.”

But Americans aren’t exactly embracing the automated workplace. The inevitable question that the new class of Luddites returns to is this: If robots can do everything we can do, how will people find jobs? Will we all have to go on basic income? Burnstein says this is the wrong way of looking at things. Robots might take away jobs, but they create new ones. The problem is getting the American workforce through a potentially difficult period of transition.

Burnstein says recent years of Automate have been dominated by a demand for collaborative, mobile robots — ones that can function more like a human worker. Smith specifically mentioned developments in robot vision technology that lets machines interact with their workspace in a much more flexible way, sorting parts by shape and color. But this doesn’t mean that human-like robots will take human jobs — even collaborative robots will need operators, handlers, and supervisors, all of whom will need to be real human beings.

“The number one challenge that our members face is they can’t find enough qualified people,” Burnstein says. “Ironically, it’s not four-year college students that they’re looking at. They’re looking at the people that have the hands-on skills to apply robots on a factory floor, to operate them, to maintain them. For every robot you see someone has to program it, build it, install it and run it.”

The solution, Burnstein says, is a change in vocational education. Automation will continue to take traditionally blue-collar jobs until the skill sets of the workforce change. Bernstein says the “hands-on stuff” that you can get in training programs at traditional vocational schools is what’s needed, not more people with four-year computer science degrees.

As Automate goes forward, Burnstein says, “you’ll see more focus on the workforce, and training and retraining and trying to better define what these jobs are to give people plenty of lead time in picking a career.” Organizations like Ramtech in Ohio are already working to re-train manufacturing workers into robot techs, and Automate will continue to serve as a meeting and recruiting ground for the American workforce, robots and humans alike.

“What we see is that where the use of robots are on the rise, unemployment is falling,” Burnstein says. “The real key to jobs is staying competitive, and predicting what’s going to happen in the future.”

In the next decade, automated technologies will likely become even more accessible to small businesses. The robots aren’t going away, but if human workers can learn to share an office or factory with them, automation doesn’t spell doom for the American workers — at least not the ones that prepare themselves for a transition. Over the next five years, Automate will continue to be a business-to-business show while also offering non-executives a look into the glimpse into the future of their sectors and a chance to prepare for change.

Attendance is going to go up.