Become an Accredited, Professional 'Buffy the Vampire' Fan

For some, pop culture texts and the fandoms that surround them are a scholarly pursuit.

Fandom is driven by passion. A love for a film, a book, a TV show, or an artist tends to bring people together to discuss, create, dissect, or even to study.

And though the word “fandom” often evokes images of comic-cons and cosplay, it has roots in much more than just a mutual nerding-out. In fact, there’s a whole community of academics who study fandom and popular texts within the context of their cultural and social impact. They’ve been called a number of different names by a number of different scholars, but Dr. Tanya Cochran uses “scholar-fans” to describe these academics.

“As a scholar-fan, part of what fuels my fandom is what I consider fun in critiquing it,” says Cochran. “‘How does it work? What does it mean? What do we do with these stories that are so powerful in our lives, that we love so much? How do they really impact us, how do they get under our skin and become a part of who we are in the world?’”

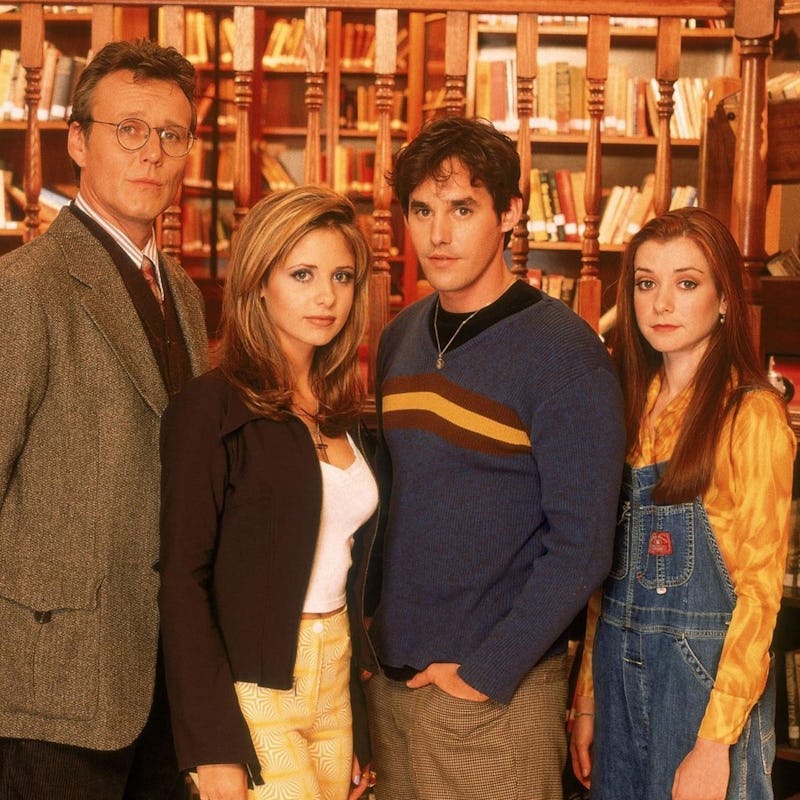

Cochran’s own scholar-fandom in the Whedonverse and her involvement in Whedon Studies came from a love of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and a subsequent discovery of scholarly work on Buffy the Vampire Slayer. In her dissertation on scholar-fandom, Cochran notes that while it was once very difficult to find scholarly work relating to television shows, when she came across Buffy-focused essays from Rhonda V. Wilcox and Susan A. Owen, the work ignited a spark that would shape her pursuit of Whedon Studies.

Dr. Tanya R. Cochran

A growing interest in scholarly articles on Buffy and other Whedon works led to the publication of Slayage: The Journal of Whedon Studies, a biennial conference, and the eventual formation of the official Whedon Studies Association, which Cochran co-founded with Wilcox and David Lavery.

The WSA and its members examine the works of Joss Whedon and his works — collectively known as the Whedonverse — from a variety of disciples. Cochran points to Dr. Linda Jencson, who works in Disaster Studies and approaches Whedon’s works from that perspective. Jencson published “All Those Apocalypses: Disaster Studies and Community in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel,” which analyzes the themes and narratives in Buffy and Angel as they relate to decision-making in a disaster, the treatment of victims of disaster, and realistic human responses to disasters.

“She uses that lens to examine Whedon’s works, and that brings a whole new level of appreciation and interest and curiosity to those of us who don’t do disaster studies to Whedon’s work,” says Cochran.

WSA still publishes Slayage, the journal that helped kickstart the association. It features articles on all things Whedon, from “Echoes of Frankenstein: Shelley’s Masterpiece in Joss Whedon’s Dollhouse and Our Relationship with Technology” to “‘I Look’d Upon Her with a Soldier’s Eye’: The Normalization of Surveillance Culture in Whedon’s Much Ado.” And as the body of work expands, so too does the scholarly exploration of that work in Slayage.

Cochran’s own work covers a variety of topics, from explorations of the impact of Whedon’s work on fan activism to the examination of the Whedonverse as a whole and the roles of different texts within that space.

“I most recently began looking more closely at Whedon’s indie film In Your Eyes, says Cochran. “What brought me to the topic was the lack of attention paid to this particular text. It’s surprising more hasn’t been done on it because it has been out for several years now. Part of the question I have begun to address is just how ‘Whedonesque’ it actually is and how it fits into the larger body of his work.”

Poster for the biennial conference from Slayage and the WSA

Beyond the publication of Slayage and the publication of academic papers on Whedon’s work, the WSA has a number of resources for anyone looking to dig deeper into the Whedonverse from an academic perspective. One of the most valuable of those resources is Whedonology, a bibliography of Whedon Studies-related work. Both published and unpublished materials are accessible through Whedonology, and it acts as something of an introduction to the academic sphere of the Whedonverse.

“[F]or anyone wanting to join the conversation at conferences and in publications, the bibliography is the place to start,” says Cochran. “It is simply invaluable.”

For a close second to Whedonology in terms of usefulness, Cochran points to The Buffy Dialogue Database, a fan-built resource that catalogs valuable information for episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, including dialogue transcripts, plot points, and arcs. For each episode, there’s a wealth of information on the content and context of clips of dialogue as well as major developments in story and mythology.

The database is an example of the interplay between scholar-fans and fan-scholars — a term Mat Hill uses in Fan Culture to describe fans who apply academic methodologies to their work in fandoms.

“The scholar-fan is someone who is formally trained as a scholar who also considers him or herself a fan,” says Cochran. “And a fan-scholar is someone who may not be formally trained in academia as a scholar but is a fan of something and thinks critically about it.”

The Intersection of Fandom and Academia

So what makes a work ripe for scholarly fandom study? What kind of media inspires scholar-fans like Cochran and what’s worth an academic deep dive?

Cochran explains the drive to study media from two different angles.

“If you’re doing fandom studies, it’s actually less about the text than it is about what people are doing with the text,” says Cochran. “And so in that sense, I don’t even think the text has to be of any particular quality to study the fandom.

She also explains that when it comes to studying a particular work, there’s some disagreement.

“If you’re turning your lens on the text itself, then there are lots of arguments about what is worthy of study and what is not.”

Cochran likens it to a spectrum. On one end, there are those who believe that only high-quality works are worth study. “On the other end,” Cochran says, you have scholars who would say that any human text that has had an impact, even on a small group of people, is worth studying because it’s had an impact.”

Think of it as a case of the Criterion Collection versus soap operas, romance novels and reality television. The Criterion Collection is made up of powerful, important, impactful works that have, in some cases, fundamentally altered the trajectory of visual storytelling as we know it. There’s a certain high brow connotation that comes with them.

Soap operas, romance novels and reality television, on the other hand, are seen as inherently lowbrow (and the fact that they’re often targeted toward and enjoyed by women is no coincidence, but that’s another discussion for another time). Even with the many criticisms of varying degrees of validity that are leveled at the quality of these works, their impact is impossible to deny. These works are seen by and affect millions of people.

Highbrow and lowbrow are constructs, and Cochran points out that while those who love supposedly highbrow works are called “aficionados” or “connoisseurs” while “fan” is often reserved for purportedly lowbrow media, we’re talking about the same thing: people who love and finding meaning in a work, whether it’s Beowulf or Harry Potter fan fiction.

“There’s a lot of pleasure in our work because it’s so multidisciplinary,” says Cochran. “We have people from all over the spectrum of ‘things you can know stuff about’, experts from all different types of fields coming together to talk about this central text and giving you a perspective on the text that you’ve never had, so it just makes it richer and richer and richer.”

Through the careful consideration of and scholarly application of interdisciplinary studies to popular culture, not only do we begin to understand our media and the effect it has on us more completely, but we also push forward the cultural conversation. TV isn’t just TV, movies aren’t just movies. The more we understand about the media that we love in the context of the world we live in, the more we understand ourselves.