Life Inside the Escape Game

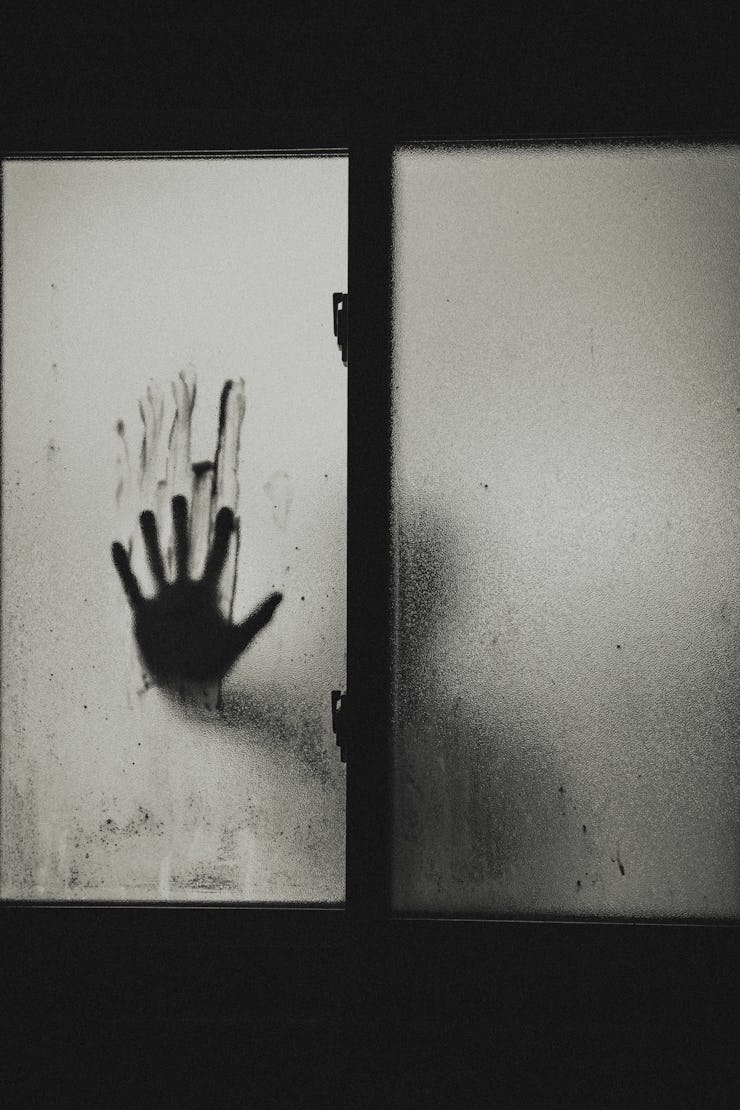

"People say that marketing's about hopes, dreams, and desires. In this business, it's more about nightmares."

Escape games, which first got big on PCs, found real-life popularity in Japan, then Europe, then the United States. Now, they’re actually getting good. The genre emerged from ambiance heavy CD-ROMs like Myst and Riven; Players learned to treat everything as a clue, to poke, prod, arrange, rearrange in the hopes of finding a way out of exhaustively art-directed confinement. The rise of torture porn franchises — Saw, Hostel, even Human Centipede — provided a visual shorthand and instilled a sense of mortal urgency. Today, thoughtfully made escape games are intentionally frightening, incredibly complicated, and very hard to make.

They are also very fun to make. Aaron Giles can confirm that.

Giles has an enviable job. He’s a designer for one of England’s more prestigious — if that word really applies — escape game companies, The Great Escape Game. Monday through Friday, Giles serves as a sadist with a corporate sponsorship. He spends a lot of time thinking about just how much you can mess with someone while still giving them a chance to solve a puzzle. Like a virtual reality designer, he builds unreal spaces in which people feel real emotions.

Inverse spoke to Giles about what makes a good game and what makes a good game designer.

Tools of the trade.

What do you do on an average day?

Because we’re expanding, it’s mainly looking at planning out the new games, the new characters and roles that people can have within the games, sorting out all of the props, sorting out the reception area, and then sorting out the marketing to go with it.

We’re trying to create, from the moment you go into reception, an immersive feeling, like you’re as far away from reality as possible.

What’s it like to design one of the rooms in these games?

People say that marketing is about hopes, dreams, and desires. In this business, it’s more about nightmares. For some reason, scary really seems to sell.

We start with a theme, and then we try and create a movie set that looks as much like that theme as possible. Then we try and create secret passages and nice bits of technology that wow people. From there, we’ll slowly start to bring more and more puzzles in, and try and just tie everything to the story and make it nice and concise.

Could you give me an example of one of your favorite sadistic, nightmarish creations?

One that we’ve got is very much themed around horror movies like Saw and Hostel. So in this room, at first, they’re blindfolded. They read the storyline to get them into the game. Then, they’re all chained up and shackled in different places of the room. They’ve got to try and, first, find out how to get themselves out. Then, as they go through, there are jump scares, terrifying blood on the walls, very ambient music, and so on, so forth.

How much of the invention is conceptual and how much is hands-on, physical design?

Yeah, so we start with a concept, start with a theme, start with a storyline. Then, it’s all about thinking about, if you really were in that position, how would you get out of it? If you really were in prison, how would you get out? Where would you crawl out of? Would you have to kill a guard? So on, so forth.

The realism is a big thing. I think the reason why people play these games — these escape games — is to escape their everyday lives, and to be set in a different setting. But, at the same time, still to create memories with their friends and families.

Is there one challenge that’s particularly hard?

Normally, each room will have two or three token puzzles. These are the kinds of puzzles that are put in there to wow people. We’ve got one that uses a lot of laser beams and mirrors, and you’ve got to try and bounce them all off each other to open a door. Stuff like that. If you think of anything that’s Indiana Jones-y, they’re the kinds of puzzles that we try to put into these rooms.

Do you get to try out the escapes yourself? Do you get to watch people try your courses?

We’ve played quite a lot of games, because we go to play the competitors’. Some of them are really good, some of them not so good. With our own designed rooms, we can’t play them, because we know all the secrets already. But when we’re testing them out, and we’ve got guinea pigs; we normally have people come in with us. We basically just sit there, silently, watching them through the game and making notes. That’s really interesting, because you can start to see that what in your head looked so simple, to somebody else can be so complicated.

What are your coworkers like?

A lot of them are very interested in video games, because it’s a good crossover — it’s like real-life video games. You’d expect us to have some weird, sadistic people working there, but I think that’s just when we have our work hats on.

Do you think some of them enjoy scaring the shit out of people? Do you?

I think you’ve got to have a little bit of a sadistic side. For instance, we’ve got a prison room, and we treat them like prisoners. We throw their hands against the walls, and we’re really rough with them. For you to keep doing that, and for you to go for it properly, you’ve got to get kicks out of it.

Also, we have CCTV, so we can watch them while they’re playing. There’s some hilarity, there. When there’s a jump scare, you can watch everybody get scared. I think the worst thing that we’ve had is that a little kid actually — bless his heart — weed himself at one of the jump scares. He was great, though. All of his mates were kind of like taking the mick a little bit. And he just manned up: He was like, ‘So what? It happened. Nothing I can do about it now.’ It was cool to see him change from being that scared to that very mature response. You know what I mean? It’s just like, ‘Ah, well, shit happens.’

Do you have another favorite story of someone getting the crap scared out of them?

One of my favorites is probably… We chained both of people up with handcuffs. After about two, three minutes, they were all out of the handcuffs. We were thinking, How did they do that? That part of the game normally takes 10, 15 minutes.

On the other side, I was talking to them and I was like, ‘How did you get out of the handcuffs, guys?’ And it turns out that one of the women had keys in her handbag for work. I kind of got the vibe that she was a dominatrix. We kept probing her to find out why she had these handcuff keys, and she was just being really coy about it. She was just like, ‘Yeah, I’m a fun time.’

Do you yourself get nightmares?

I don’t remember many of my dreams but I’m sure I do get nightmares. I do think that that’s a big part of the games, as well, because a lot of these settings are like living out your nightmares. It’s almost like the reason why we have nightmares to begin with: When you’re having your nightmares, it’s like you’re playing out what would happen in a bad situation, how you would deal with it.

That’s what I think a lot of people get out of it. They have these settings where they could be trapped by a serial killer, or they could be locked in prison, and it’s almost like living out your nightmare.

Do you think the popularity of escape games will hold up long term?

I think the whole reason why they’re so popular is because, in this day and age, people are starting to care less and less about material possessions. What they care about, more, is having experiences. Doing fun things with your friends and family; making memories. I think that’s why this trend’s really kicked off, because it’s a mixture of that, and it’s something different, new, and exciting. You can just go and get locked in a room for a thrill; you don’t have to paraglide off a mountain.

This interview was edited for brevity and clarity