Madame Tussauds Embraces the Unreal

An inside look at the technology that makes ghostbusting possible and the mentality that keeps wax relevant.

Slimer has a home in Times Square because, fifty years before Sir Arthur Conan Doyle made 221B the fictional home of Sherlock Holmes, Marie Tussaud opened a museum a few blocks further down London’s Baker Street. Filled with gruesome wax dummies depicting the victims of murders and the celebrity murderers themselves, this eponymously named, morbid institution was the Louvre of low-brow wax sculpting. Tussaud’s goal was not to provoke discussion, but to elicit a visceral reactionby immersing visitors in simulated mayhem. She succeeded and museum open branches all over the world. There are currently 23 locations in eight countries and Tussauds parent company, Merlin Entertainment, is set to put another jewel in the crown when a New Delhi branch opens in 2017.

Waxwork has, against considerable odds, remained a relevant medium for Hollywood’s most valuable intellectual property — the rebooted Ghostbusters is set to open big — despite the advent of holograms (hell, despite the advent of TV). This is less a tribute to the medium than it is to the strategic thinking at the heart of Madame Tussaud’s current strategy. The museum has ceased to quietly pivoted from verisimilitude to the unreal. For visitors, this can make a visit both incredibly engaging and bizarrely post-modern.

On July 1, Madame Tussauds latest attraction, The Ghostbusters Experience, opened tin New York. A recreation of characters and sets from the new film, the exhibit is flashy in the way most modern Tussauds exhibits are flashy. It’s not a standalone attraction. A few halls away lurks Ghostbusters: Dimension, a virtual reality experience that isn’t set up to look like the main attraction, but might be just that.

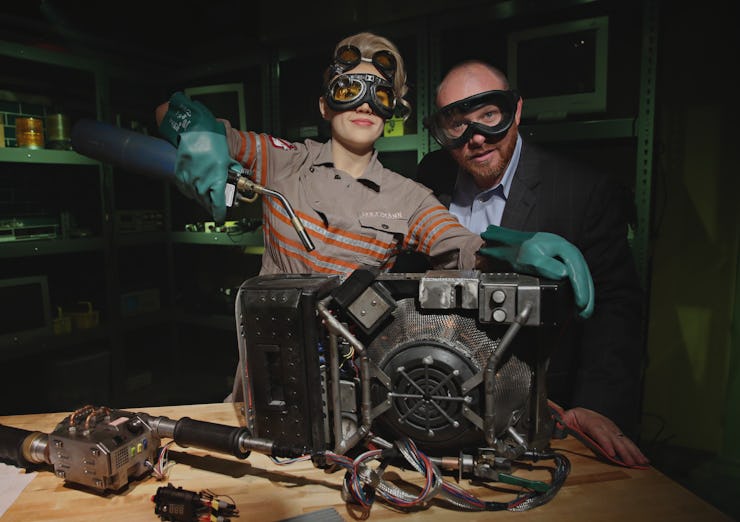

Ivan Reitman poses for a photo with a Madame Tussauds figure of Ghostbuster Patty Tolan (portrayed by Leslie Jones) inside Madame Tussauds New York highly-anticipated all new Ghostbusters Experience on June 29, 2016 in New York City. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for Madame Tussauds)

There’s a tension between the exhibits — as though visitors are time traveling back to a Victorian version of the eighties where VR helmets and quasi-haptic suits were common. The wax is wax; the VR room could be referred to somewhat accurately as the “holodeck.” And prices reflect the different offerings. Ghostbusters Experience is $29.75, but upgrading to include the VR Ghostbusters: Dimension is $49.75. In short, the business people at Madame Tussauds have no trouble publicly acknowledging the waning value of access to a virtual wax reality in light of the advent of digital ones. And while one might interpret the integration of newer technologies as a desperate attempt to stay relevant, there seems to be a bit of symbiosis.

The wax let’s Madame Tussauds continue to be recognizably Madame Tussauds. The virtual reality let’s Madame Tussauds make money.

And it’s not as though the physical, real-life aspects of the Ghostbusters Experience aren’t impressive. The new Ghostbusters HQ is lovingly recreated with Kate McKinnon’s Holtzman hard at work on a proton pack inside. There are ghost-detecting PKE meters and projected spooks in the containment unit.

“This is 100% you being in the new Ghostbusters movie. You touch the walls and its a New York brownstone. These are real bricks,” says Eric Fluet, the New York head of Marketing and Sales for Merlin Entertainment. As the Madame Tussauds brand evolves, its all about creating immersive experiences, of being fully involved.”

Then why didn’t the PKE meter turn on? “Well, thats rubber. But it’s a real prop from the movie. Leslie Jones held that.”

The definition of the word “real” is hard to figure in the context of a Ghostbusters exhibit devoted to cinematic verisimilitude. Props co-mingle with wax likenesses and paying customers. This is physical space, but the opportunities for interaction are more limited than they are in virtual space. It is more real and also less.

Down the hall, the proton packs actually do something.

The Void, the nihilistically named company responsible for the VR setup, bills itself as a “hyperreality company.” If Ghostbuters: Dimension is any indication, this is because their product boast to do for VR what Kodachrome did for film. It’s bright, it’s immediate and it will not be ignored. Freshly outfitted Ghostbusters are tasked with investigating a particular haunting of particular building. The proton-blaster feels warm when they fire and crossing the streams produces insane results. Standing on top of a virtual building is a frightening experience, so much so that venturing out on the platform is a tentative endeavor.

“I think were getting really close,” Ken Bretschneider, CEO of The Void, responded when asked how close he felt his technology had come to the haptic suits imagined in science fiction books like Ready Player One. He’s particularly proud of a technology called Spire, which can do full body-tracking, so users can feel more like they’re occupying physical space. The tracking in [Ghostbusters: Dimension] is only partial. “Well eventually need eye-tracking and more to really do fully socialized experiences, but that’s where we’re heading,” Bretschneider explained.

What it looks like while you're in the 'Ghostbusters: Dimension' VR

Right now, The Void’s VR helmets and blasters and tech exists as part of the Madame Tussauds attraction, though it could conceivably exist somewhere else on its own. And though the partnership between The Void and Merlin Entertainment seems mutually beneficial, the two are businesses are hardly tethered to each other. Merlin, which has seen its profits rise 10 percent since going public in 2014, will certainly keep looking for new technologies designed to keep things immersive. The Void will look for new partners, presumably using the Ghostbusters Experience as an example of their best work.

Part of this can certainly be attributed to the fact that Merlin owns and operates various Legolands as well as the Madame Tussauds brand, but it’s not like they’re closing these wax museums left and right. According to market research, part of the reason why Madame Tussauds remains a counterintuitive money-maker is that wax museums require little investment. Essentially, Madame Tussauds is creating a lot of the same products it always has and selling access for more. And the VR stuff is done out of house, so they don’t have to front the R&D budget.

Inevitably, they will choose a few technologies that work particularly well and try to install them in their strategically located tourist hubs. This is one of the ways in which consumer virtual reality will reach the masses before the price point of the Oculus comes down.

In some ways, Madame Tussauds is doing what action filmmakers have done for twenty years, straddle the divide between practical and digital effects. This works because the technologies meet halfway. The wax dummies exhibit features projections; the VR experience is all about real movement. The line between real and fictional worlds gets blurry, which is generally a sign someone is about to make a lot of money.

In the original 1984 Ghostbusters Peter Venkman(Bill Murray) tells Ray Stanz (Dan Aykroyd) that the “franchise rights alone will make us rich beyond our wildest dreams.” Aykroyd, who opened House of Blues in 1990, took the dialogue to heart — and for good reason. The intellectual property that constitutes the bulk of the attraction to Tussaud’s Ghostbusters celebration, is worth a fortune, but there are other fortunes to be made with it. In the 80’s, that was good news for toy makers. Now, it’s good news for anyone who can provide a visceral Ghostbusters experience. For now, Merlin has figured out a way to do that using mixed media, but the waxless wax museum still feels inevitable. What doesn’t feel inevitable is the name written in flashing lights on that building.