Why Three-Parent Baby Embryo Research Doesn't Incite Pro-Life Backlash

For now, the international "14-day" rule for embryo research is keeping the inevitable moral outrage at bay.

Pro-life activists have already made their voices heard this election season, with fury about the heavily edited Planned Parenthood sting videos driving many of the early debates. But as news of fresh human embryo research progress, including the creation of viable three-person babies, makes headlines, activists have been uncharacteristically quiet. While scientists working with human embryos certainly face some backlash, they’ve been largely spared the wrath of pro-life groups, who seem less convinced that life begins at conception when life begins in a lab.

Their apparent lack of concern represents the state of the research — or at least the way it’s perceived by the public. For scientists, that indifference has offered a fragile peace in which funding and publicity remain available.

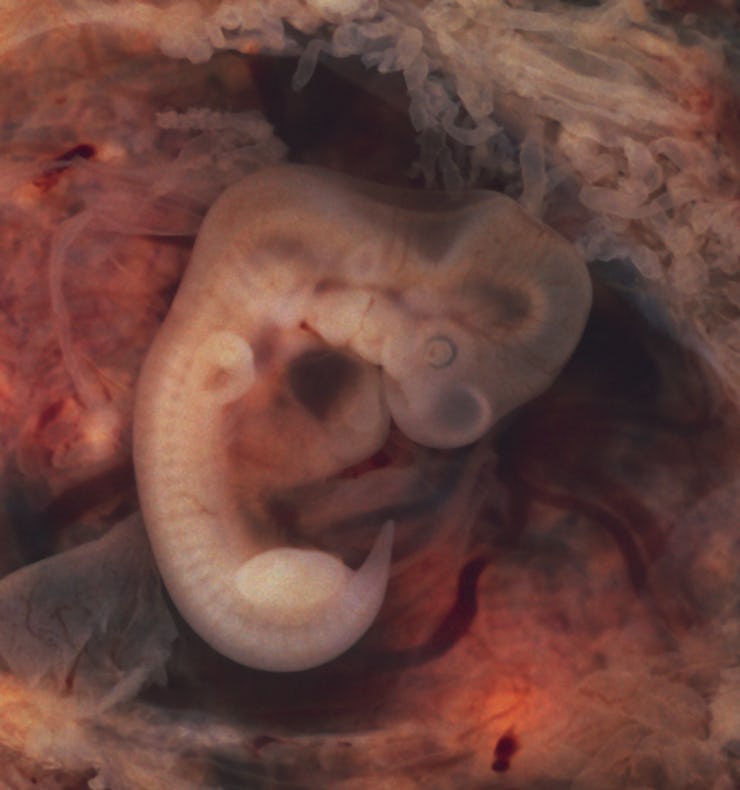

The three-person embryos arguably haven’t been allowed to grow to the point that they constitute a “life” because most scientists working with human embryos are bound by an international rule that forbids growing embryos past the 14-day stage, established to prevent researchers from breaching ethical boundaries as they figure out the scientific specifics of what makes a ball of cells a human life.

The 14th day is significant because that’s the time when the “primitive streak,” a faint structure visible on an early embryo, appears. This is considered by many scientists to be the moment when a mass of cells becomes a biologically and morally significant individual. This limit has, until recently, been largely symbolic. Growing embryos for 14 days outside of a uterus is hard to do, but we’re getting better at it.

The science is developing rapidly. In early May, scientists publishing in the journal Nature were able to keep embryos alive outside of the womb for almost 14 days, a feat that many thought was impossible. And, this week, British scientists also publishing in Nature showed that a new technique for making three-parent babies was safe; after conducting a series of tests, they found that the early-stage embryos they created in the lab using DNA from three people were just as healthy as embryos made using normal in vitro fertilization methods. Procedures for making three-parent babies are being developed to avoid the transmission of mitochondrial diseases from mother to child.

As with all research, there will be collateral damage. Developing balls of cells are usually destroyed before the 14-day mark if they don’t die on their own, just as “pre-embryos” (what fertilized eggs are called before they’re implanted) produced through in vitro fertilization are discarded if they’re not ultimately used for pregnancy or donated to research. Pro-life groups have rallied against IVF for killing “extra” human embryos, but they haven’t yet turned that outrage toward embryo researchers, even though the main issue — the destruction of human cells — is largely the same.

The inconsistency of their activism has been called out before. Washington Post columnist Margo Kaplan, noting the disparity between the amount of pro-life outrage directed at abortion clinics versus that targeting IVF research, argued that the concern at the heart of the pro-life argument isn’t the protection of human life but diminished control over women’s bodies.

Some human embryo researchers, anxious to push the science even further forward, have called for a reassessment of the 14-day rule. If it happens, it’s guaranteed to capture the attention of pro-life groups that have dismissed the early embryos as non-viable. At the rapid rate the research is developing, it’s entirely possible that the scientific community will have to at least consider it. When they do, it’d be a good for them to come up with a game plan for dealing with the pro-life set, too.