Is Google's VR Tilt Brush the Future of Art, a Legal Acid Trip, or a Gimmick?

Two professional artists and the brain behind Visual Art Sessions consider what it means to paint in three dimensions.

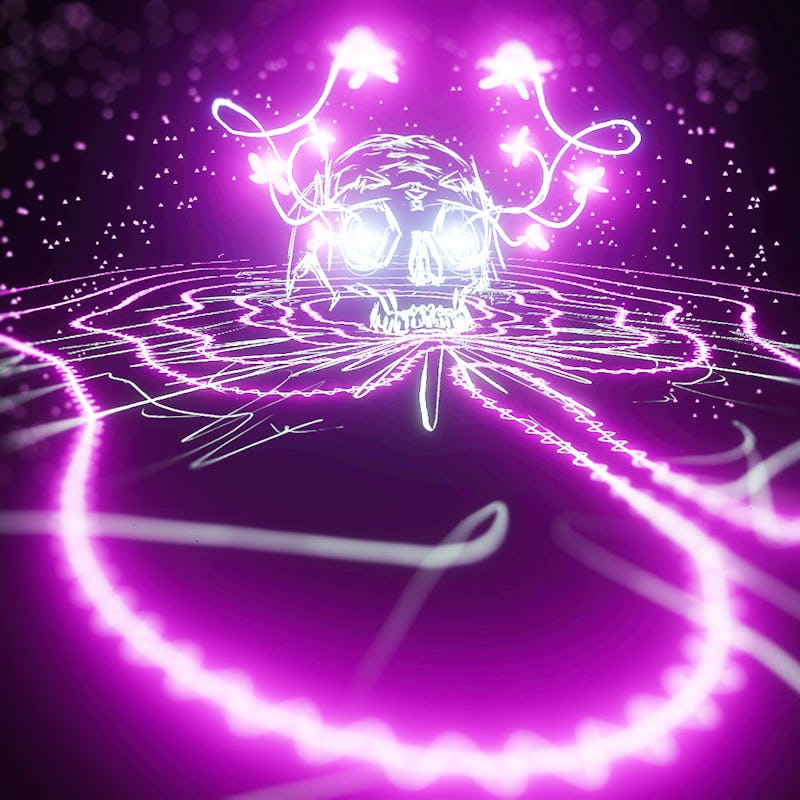

Tilt Brush is the sort of Google project that engenders a googolplex of good will. It takes virtual reality and transmogrifies it into an artistic medium by allowing artists to illustrate a virtual, 3D room with variegated strokes and colors. In the hands of a talented artist, the technology quickly yields beauty so it’s no wonder the demo videos blew up online. Still, it’s unclear whether Tilt Brush represents a real leap forward for the art world or whether it’s just an expensive toy.

One thing is clear: Words can only go so far to explain the experience. Those who have tried it sound like LSD enthusiasts, explaining patiently that, until you try it, you can’t really understand.

Jeff Nusz, the tech lead for Google’s Data Arts Team, tells Inverse that when he first tried out Tilt Brush he was blown away by how intuitive it was. It was a VR experience unlike anything that he’d tried to date. But, as he attempted to describe to others how it felt to create in that medium, he flailed. So, naturally, he dreamt up a new way to share the experience: Visual Art Sessions.

He and his team invited seven professional artists to Google and asked them each to give Tilt Brush a shot. There was an illustrator, a concept designer, a fashion artist, an installation artist, a pair of street artists, and a sculptor. Nusz explains that he hoped to not only capture beautiful works of unique VR art, but also to capture the creation process.

Artist acclimation took all of 30 minutes, far better than the anticipated half-day, which speaks to how natural virtual reality can feel. The team recorded each artist’s perspective, but also recorded their bodies in 3D. The finished products are videos that allow viewers to observe artists from the first or third-person.

One artist, in the behind the scenes video, described Tilt Brush as “legal acid.” Nusz elaborates.

“It’s quite strange,” he says. “You start with this empty void of a room, and you just start building up, through your motions and choices, this new environment around you. It comes straight from your mind into reality, but then the reality of it is realer than you expect.”

Andrea Blasich, the sculptor invited to use the Tilt Brush, was arguably able to create the most concrete or real-seeming virtual artwork. Blasich’s success makes sense, given the medium. “Whereas paint drips,” Nusz says, “with Tilt Brush, each stroke you create hangs in space and becomes this structural object.” He therefore had perhaps the easiest time converting his skills.

Blasich, who’s a traditional sculptor by trade but has also worked with the likes of Pixar, Disney, and DreamWorks, explains that he was nervous at first, and that it did take him some time to adjust to the medium. “At the beginning, it felt more like a painting, a traditional painting,” he says.

Given that it was Google, he felt that the pressure to produce. The room was hot, so he was sweating; he had to take intermittent breaks to give his eyes a rest. But, “when you get into it,” he says, “you forget about what’s around you.” On his filming day, he created ten virtual sculptures, each in a 20-minute session.

Blasich repeatedly used the words “amazing,” “incredible,” and “unique” in describing his experience, and he expects VR art to take off in the future. Still, Tilt Brush is in its early stages, and using it requires “a different mindset.” The tool tries to “emulate reality in virtual reality,” he says, but “there is no more reality than touching a real object, being in a real environment.”

And that’s the primary shortfall, one that critics would say makes Tilt Brush — and VR more broadly — more of a gimmick than a paradigm-shifting medium. Aparna Sarkar, a Brooklyn-based painter, would agree. “I don’t think that the medium has been justified,” she says. “There would have to be a really compelling reason for me to think it was important to demonstrate my concept through this particular means, which I don’t feel at the moment.”

The other problem, Sarkar points out, is that few people can see Tilt Brush works as they were meant to be seen. The YouTube videos are cool, but seeing a video of a Tilt Brush painting is on par with seeing a photograph of Winged Victory, which is to say inadequate. “It’s really important that as many people as possible get to see and experience a work,” Sarkar says, adding that the artwork can only be said to exist “when you’re looking at it through virtual reality glasses.”

Nusz freely admits that watching a VR experience on a 2D screen is “not the same as being in there,” but it’s a start. And while Nusz doesn’t necessarily think Tilt Brush is the future of art, he thinks it’s “a future of art.” The mere introductions of new paints has birthed entire artistic genres, he argues. Premixed paint mobilized artists and led to Impressionism in the same way that chemically-enhanced colors created the unreal dynamism of Fauvism.

Blasich can envision a day where VR art earns its keep. On that day, art spectators become art experiencers, able to “feel the artist’s emotion.” Right now, that may require some LSD. But, in the future, VR could suffice. On that day, Sarkar might be sold.