Can a Crowdfunded Racehorse Win the Kentucky Derby? Geoffrey Gray Will Find Out

True.Ink's Geoffrey Gray tells _Inverse_ why it's not an insane idea.

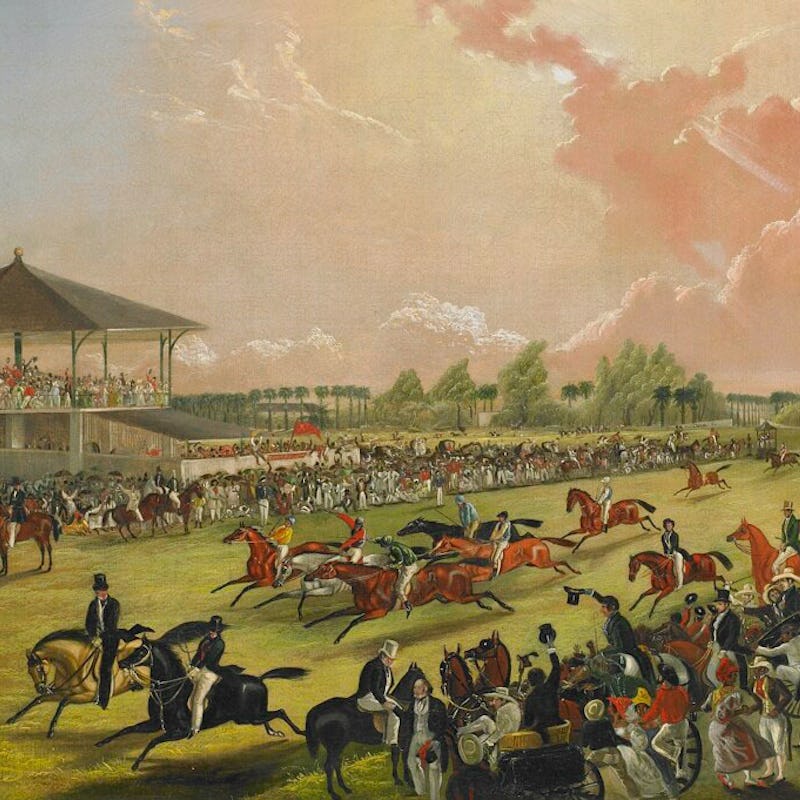

True.Ink, a new experiential journalism outfit, has just issued an invitation to the public at large to invest in — of all things — a racehorse. Once a popular but elite event, horse racing has fallen out of favor with Americans. Geoffrey Gray, the former journalist “happily seduced by an underdog tale,” says collective ownership represents a potential solution to the sport’s audience problem. Currently, only gamblers and owners have a stake in most horse races. What if the Kentucky Derby’s bleacher creatures did too?

The question the “People’s Horse” project presents about horse racing runs parallel to the question True — which was inspired by a pulpy 1930s periodical of the same name and operates from True.Ink — presents about the world in general: Isn’t it more fun to participate? Rather than writing “How to Make Moonshine,” for example, True wants to distill stuff and get its readers — or “friends,” as Gray thinks of them — drunk.

“I think people want community and authenticity more than ever. They want to meet people that are real, and they want to have experiences that matter,” Gray says. “Which is why we’re buying a horse.”

On the face of it, crowdfunding a racehorse seems eccentric. Horse racing has long been a sport for the privileged. Traditionally, one rich patron invests his or her money into a horse, trainer, stables, and so on, then asks some money friends if they want shares.

True’s effort to crowdfund a champion is an attempt to lend new life to the ancient tradition. Embedded in that tradition, Gray says, is symbolism, and symbolism that our culture today lacks. “A horse represents hope, a horse represents power, a horse represents strength. A horse, in a lot of ways, represents healing. And a horse represents a connection to a certain part of time and history that has become very foreign and unnoticeable to many urban slickers who just go seamlessly from their iPhones to their computers back to their iPhones to their Netflix accounts and iPads.”

Horse racing, Gray adds, is almost antithetical to the fast, marketing-driven league model that dominates both sports and modern society writ large. “There’s a certain inefficiency to the horse-racing model,” he says. “It revolves around this animal. If it’s windy, if the horse has a sore shin — anything could happen that could delay or propel the activity. It sort of forces you to become maddeningly patient.”

And watching is more fun when you’re an owner, even if your ownership stake is small. When you know the horse and feel a relationship there, you also feel a thrill that has traditionally been reserved for the rich. Gray wants to give people access to the horse, yes — but mostly as a means to access the experience.

To become a full-blown “Founding Stablemate,” you donate $100. For the money, owners get updates, the opportunity to help choose and name the horse, and also a chance to meet it in person. The People’s Horse will be stabled on Long Island, at Belmont Park, but non-New Yorkers can still check in with the as-yet unnamed horse remotely.

And yes, Gray has considered the long-term well-being of the horse as well as its immediate training. Stablemates will vote on trainer selection, but the trainer will make health and conditioning decisions because the wisdom of crowds only extends so far. The horse’s quality of life and care will be paramount. True has already lined up a farm for the horse in the event of an injury or early retirement. “Obviously, we don’t want to ignore the will of the people,” says Gray. “At the same time, there is a live animal and there are serious issues that we have to be responsible for.”

Still, Gray is intrigued to see what comes of this collective parenting. “The truth about horse racing, and the challenging part of the story — for us and for everybody — is going to be how to negotiate the emotional attachment with the animal with the sport that the animal is in. As with many things in life, there’s a real challenge: how do you negotiate the thrill? Can you still get behind a horse that doesn’t win?”

“We’ll be entering a long, secretive world that is at once ugly, beautiful, old, and changing,” says Gray. “And we don’t know where it’s going to go.”

That, perhaps, is the core difference between what Gray is trying to accomplish now and what he once did. He used to tell stories. Now he’s creating the conditions for stories to play out.