Richard Branson's Balloon Doc Shows That the Spectacle Is the Mission

The documentary provides a compelling look at Branson’s past adventures, but it also raises concerns about how he’s approaching the future of private spaceflight.

There’s a scene in Don’t Look Down where Richard Branson is visibly and audibly frustrated.

“Bloody … ah fuck,” he groans, rubbing his hands on his face. “I can’t bear it.”

The Japan launch of his hot-air balloon, the Virgin Pacific Flyer, is being postponed due to bad weather. Branson, cognizant of his image and the image of his company, begins to complain that he and his team are going to become a laughingstock.

The new documentary — exploring the attempt by the Virgin empire billionaire to be the first person to ride across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in a hot air balloon — premiered Tuesday at New York’s Tribeca Film Festival, with Branson in attendance. It clearly conveyed this message: the spectacle of the mission is often just as important the mission.

Back in the film, Branson, now faced with the weather delay, should have known there would be problems. The launch site couldn’t have been a poorer choice. Instead of selecting a valley that would be protected from winds and turbulence funneling against the mountain, Branson and his team chose a plateau so that local villagers and media could gather around and watch the spectacle unfold.

And what a spectacle it was: The deflated balloon froze overnight outside, causing the outer layer to begin peeling off the next day when it was time to launch. At first, Per Lindstrand, the aeronautical engineer who designed the balloon and Branson’s co-pilot, said that the areas where the layer was falling off were “not essential.” They could still make the trip. Once the whole silvery sheen fell off as the balloon was being inflated, it was clear all was lost.

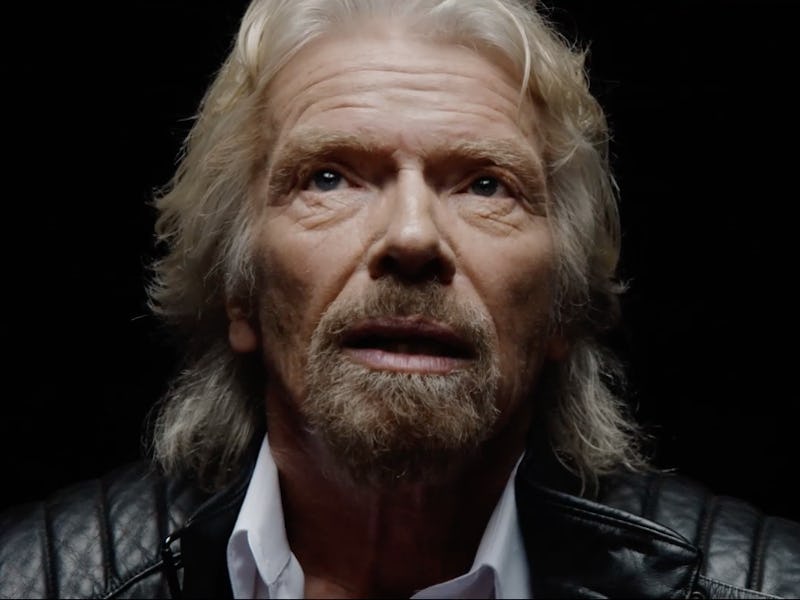

Richard Branson discusses 'Don't Look Down' in New York City on Tuesday.

It speaks volumes that Lindstrand and Branson were still willing to go through with the trip even as the balloon was literally coming apart. Five years earlier, when the Atlantic adventure began, the pair lost three-quarters of a ton of fuel immediately after liftoff, when a ground line snagged off two tanks from the side. They made it across the ocean, but lost control when attempting to land the balloon in Ireland, and ended up having to jump out before the the craft crashed into the North Channel:

A water landing.

Then, when the Pacific flyer finally took off for Canada in 1991, Lindstrand and Branson experienced catastrophe when they attempted to eject one of their empty fuel tanks, and ended up losing two other full tanks along with them. At that point, the pair were staring straight down at the chance they would die in the middle of the ocean.

Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo

How does any of this relate to Virgin Galactic and private spaceflight? The documentary offers a brief small glimpse into Branson’s thought process, but these scenes and others are illustrative of the fact that what Branson was pursuing with these adventures wasn’t to demonstrate new heights in technical and scientific prowess, or even explore parts of the world beyond what humans had ever seen.

The hot air balloon trips, instead, fit snugly into Branson’s drive to participate in the publicity of adventure and do things humans have never done before.

That in itself is far from a negative. In fact, it’s virtuous for one to muster courage in the face of death and failure — and strive to accomplish new things. But Don’t Look Down inadvertently shows us that Branson neglects to take the proper steps to mitigate all potential risks.

Astronauts, for instance, spend years in training before even having the chance to be considered for a mission to space. They are run through every single piece of equipment; memorize every contingency plan; and immerse themselves in a nearly-complete knowledge of how their spacecraft works and what they can do to keep themselves safe should problems arise. The lesson behind the Challenger tragedy of 1986 is that you can’t rush spaceflight for the sake of public excitement. The consequences are disastrous.

Branson, in both of his balloon expeditions, doesn’t exude this expertise. He and Lindstrand run into problems that were very clearly avoidable. The film shows how he constantly defers to Lindstrand at almost all points in the journey. Branson pours in all of this money into making these adventures work — and frets over the hit he and his company will take in the media when things don’t work — but he seems noticeably disconnected from understanding how this trip is actually supposed to work. He cannot troubleshoot the obstacles.

There’s no reason to think Virgin Galactic — a company that will serve the paying public, as opposed to his hot-air balloon adventures — but the film suggests Branson hasn’t yet moved beyond a focus in PR at the cost of perfecting the details behind his projects.

The post-viewing Q&A with Branson only underscored this point. Asked about whether he might do another documentary about the Virgin Galactic’s maiden spaceflight, he said there was already about ten years of footage collected that could be used.

“Maybe we’ll do a film about that in [another] 10 years,” he said.