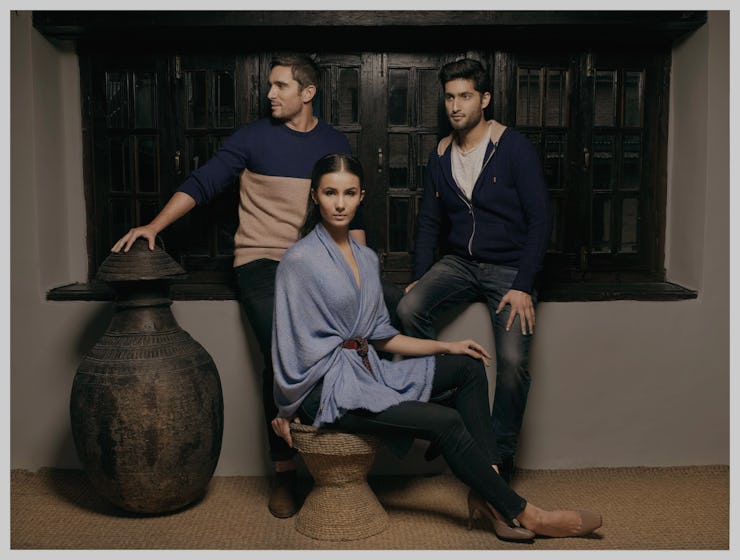

Want to Sell Cashmere Sweaters From Nepal? MONK's Founders Did, So They Moved There

How two Wharton grads launched a fine clothing line straight from the Kathmandu Valley.

Public Factory in New York City is the kind of place I walk by without hesitation. It’s a designer clothing shop located at the Soho Grand Hotel: too rich for my blood, I imagine, or, at least, too fashion-forward for this avowed band T-shirt acolyte. But, I step in to meet with Rabindra “Rabi” Shrestha. He greets me outside in the rain — I’m a little late — and takes me into the shop where his company MONK, a Nepalese cashmere outfit, has a space to show its wares. I feel the hyper-soft sweaters and immediately realize that — maybe, just maybe — I should come into these kinds of places more often. And I haven’t even heard MONK’s story yet.

Shrestha and his Wharton School classmate, Harris Atmar, launched MONK in November of 2015, but Shrestha has been thinking about the idea for years. “I grew up a stone’s throw away from where most of our manufacturing is done in Nepal,” he tells me at the Public Factory as we pet sweaters and scarves. “Everything is handmade by artisans we sourced on the ground in Nepal. It started because every time I used to wear it — cashmere is a very normal material in Nepal — somebody would give me a pat on the back or give me a hug they would say, ‘That’s the softest sweater I’ve ever touched.’ After a while, people started asking me to bring stuff back from Nepal whenever I went home or a couple friends who came to visit said, ‘This is the most amazing thing,’ and they’d buy thousands of dollars worth of stuff. So I said, ‘Why not turn this into a business of sorts?’”

The two former investment bankers got to planning and, then, moved to Shrestha’s native Kathmandu Valley, where cashmere has been manufactured for thousands of years. “The two of us worked on the design — we have designers in New York — but we realized we needed to be on the ground in Nepal, at the factory, to get everything right. So we moved to Nepal, actually, for a couple months,” he says. “Most of the factories, you imagine garment factories as being these huge operations. But in Nepal, it’s really just small, family-run businesses with maybe 20 or 30 knitters. It’s really quite a quaint setting. They’re all done by hand, so it’s almost workshops more than factories.” Shrestha tells me that MONK sources from four factories that otherwise do fine craftsmanship for Italian and French designers.

Shrestha makes sure to point out the New York City-designed elements — color tipping on the end of a v-neck or the contrasts on the hoodie, their best seller — but the story keeps coming back to the artisans of Nepal. “When I say everything is made by hand, I really mean everything is made by hand,” he tells me, “because even the buttons are hand-carved.” Shrestha shows me the box the sweaters come in. It just might be the most beautiful box I’ve ever seen. And that’s a sentence I never thought I’d ever write. It’s handmade with all the right angles and contains papers that are made from the pulp of a Himalayan plant. “Even the printing is done by hand, so it’s hand-screen printing,” he says, “It’s not printed by a machine of any sort.”

Some of the papers included are postcards of the people who work on the sweaters. Here’s just one blurb about Ramsurad Biswakarma:

As Senior Carver, Ramsurad’s grandfatherly presence is strongly felt in MONK’s button factory. Having spent 22 years carving and chiseling raw materials such as stone and wood into button-sized discs, Ramsurad embodies the characteristic most associated with craftsmanship, dedication. With a wide, unwavering smile, Ramsurad recounted his journey from Varanasi, India to the Kathmandu Valley as if it happened yesterday. His past is written but his future lies in the lives of his son and four daughters, all of whom are currently studying or working in India. With the marriage of his eldest daughter due to occur early next year, Ramsurad’s future has much to be excited about.

MONK has intertwined itself with the people of Nepal, dedicating a portion of its proceeds to the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust and 108 Lives Project. The former is busy rebuilding UNESCO World Heritage Sites demolished in last year’s earthquakes, while the latter teaches locals a craft. “They work with the disadvantaged youth and disadvantaged women of Nepal to help them be financially secure in an environment that is pretty tough for them right now,” Shrestha says of the 108 Lives Project. “When we make a sweater, there’s a lot of wasted cashmere. There’s a lot of scraps that are wasted. Usually factories will pile all of that up and get rid of it. What we do is we use all that scrap cashmere and we train the disadvantaged women in these different camps or slums — as you might call them — to make blankets or bracelets. That way there’s no wasted material and we’re helping somebody be trained in a skill that they can hopefully use in other avenues to make money. Also, we’re buying back what they make and then we sell on.”

When Shrestha and Atmar were living in Nepal, they saw firsthand how tough making a go of it there can be. There was a politically driven blockage of oil coming from India, so virtually all cars were off the road. The pair would walk from Shrestha’s family’s home to the nearby factories each day. The diligence paid off, with MONK selling its high-quality cashmere in New York, Philadelphia, online, and in various pop-ups. “For the United States, we thought: Nepal has amazing artisans,” Shrestha explains. “Whether it’s the button-makers, the box-makers or even the knitters, amazing artisans that really haven’t had a chance to share their skills on the world stage because, A) it is tough to do business in Nepal given the current environment, and B) the boom of Chinese industry. You can just show up to a factory in China, say you want A, B, C, and they’ll produce 1,000 overnight. I really wanted to bring out the heritage of the material. Cashmere and sweaters and all of these products really have a bit more soul than just getting it off an assembly line in China.”

Because of its tight relationships with its artisans, MONK has managed to keep the cost of its cashmere sweaters relatively low: from $130 to $380. It’s the kind of price point that Shrestha and Atmar hope could make Nepalese cashmere ubiquitous in the U.S. Or, at least, make more people stop in their tracks when they’re walking on a rainy day in Soho.