My Dad Wrote the Book on O.J. Simpson, and Yet That Case Still Baffles Me

Here's why I'm looking to FX's 'The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story' to explain a murder trial that defined my earliest memories.

From my earliest days, I was an O.J. skeptic. And I do mean my earliest — I was 18 months old the day Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman died in 1994 — so I don’t mean to say I’ve always had a strong opinion about O.J. Simpson’s guilt. In fact, quite the opposite. Almost as soon as I could speak, I was objecting to people spending so much time obsessing over the case.

In particular, I objected to my dad, Jeffrey Toobin, spending so much of the intervening time before the ultimate not guilty verdict covering the trial in Los Angeles, across the country from our home in New York. His reporting on the case earned him a book contract that turned into The Run of His Life: The People vs. O.J. Simpson, which now forms the basis of The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story, an FX miniseries that premiered Tuesday.

At the same time I was learning to speak, the case against O.J. was fast becoming “the trial of the century,” and a slew of young journalists, Dad included, were slogging it out for leads, access to sources, and any kind of exclusive scoop. I, on the other hand, was becoming a toddler who missed his father. “No O.J., Daddy,” was one of the first phrases I learned to repeat. Every time I kissed my dad goodbye for another week away from home, I was already frustrated that he and everyone else cared so much about one guy, whether he killed two people or not.

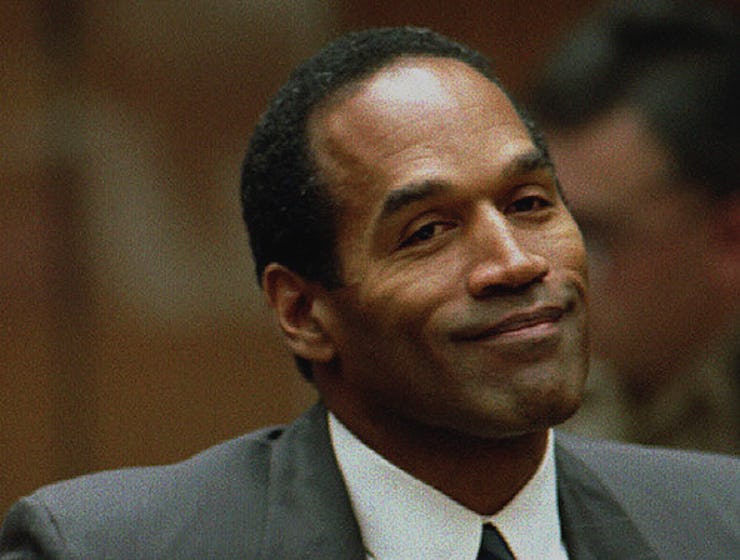

(My dad attended the reading of the verdict and briefly appeared on TV right after the jury declared O.J. “not guilty” at about 1:05 in the above video. He is sitting next to the Goldman family.)

My perspective was unique, I realize, but I expect a lot of people around my age feel similarly about O.J. We don’t care that he was a great football player in the 1970s, or great in college in the ’60s. We barely care that he was in the Naked Gun movies, which, admittedly hold up pretty well, considering it’s been 30 years and the costar wrote a book called If I Did It, in which he describes how he would have killed the wife everyone thinks he actually did kill.

All my life, I’ve heard that the O.J. case was bigger than we can fathom. That you couldn’t turn the television on during the trial without seeing O.J. and hearing about the case, because the only two television stations with 24-hour news at the time, Court TV and CNN, gave the trial wall-to-wall coverage. And without the internet to provide relief, many people spent months of their lives glued, willingly or not, to O.J. news.

But there is a sort of revisionist history in this understanding. Television plays foremost what audiences want to watch, and the entire country, including the print media — my dad was a full-time magazine writer — covered the case non-stop. They say O.J.’s trial was the first reality TV show; it fascinated people with a peek into the lives of the rich and famous. But a voyeuristic thrill alone would not have maintained the cultural relevancy that O.J. has held during the past 20 years.

The assumed wisdom today is that O.J. got away with murder. You may know nothing about the evidence, football, or The Naked Gun, but you know there was a guy named O.J. who got away with murder in the ’90s. Even if you doubt whether he did it, you know that questioning O.J.’s guilt is only a step removed from openly wondering about a second JFK shooter. His name has become a synonym for escaping justice, though he is currently serving between nine and 33 years in prison for a separate incident in which he broke into a hotel room to retrieve stolen memorabilia while armed.

O.J.’s trial embodied a specific kind of rigged American justice. Because O.J. is black and still managed to get off, because he was rich and could hire the best defense, the case suggests that America’s judicial system stacked more against the poor than against black people. But O.J.’s team also successfully argued to a jury of white and black Americans that the Los Angeles Police Department planted evidence against O.J. because he is black. Since the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin and the aggressive non-indictments of police who shot Michael Brown and Tamir Rice to death, the notion of a jury believing an alleged murderer before trusting a cop seems almost outlandish.

So it’s not hard to imagine what obsessed America about the O.J. case. Was it that a famous black man killed his beautiful white wife? Was it the allegations of police misconduct?

There are also the hypotheticals. Would the same case draw as much attention today? Would it have been the same spectacle if a white football player had killed his wife?

And now that the FX series and an ESPN documentary series that will premiere later this year are introducing O.J.’s trial to a new generation, all these questions are bound to come up again. The timing couldn’t be better, from a pop culture perspective; with HBO’s The Jinx and Netflix’s Making a Murderer reaching so many people, the O.J. circus is primed to retake its place atop the mantle of American true crime. The show considers all these elements and heightens them Ryan Murphy-style: The Simpson case is about money, fame, race, beauty, and sex — subject matters that Americans, historically, cannot get enough of.

What will determine for me whether the coming series are a success is not only how they portray O.J. himself, as a fugitive from the law or the victim of a racist police department, but also how they portray America’s fascination with the trial.

The cast and creators of the FX miniseries, including my dad on the far right of the bottom row, discuss the O.J. case.

From my earliest days, I have heard about the O.J. trial and watched Americans debate endlessly the minutiae of the case. Do I think he did it? Of course. My dad knows far too much about the case and has far too strong an opinion that I could never manage to maintain much doubt for long. But then even I, who has no reservations about O.J.’s guilt and who really doesn’t understand why the hell anyone cares about the case, couldn’t take my eyes off last night’s premiere. Maybe it’s only because I’ve heard the “No O.J., Daddy” story so many times throughout my life and will finally have the chance to live the case as my family, and all of America, did in the ’90s. But I’m guessing there’s more to it than that.

O.J. defies what it means to be accused killer in the United States. He convinced a jury of his peers that this country is so racist that a major police department could frame an innocent black man for murder. How his legal team managed to pull that off, and why America immediately rejected it following the verdict, will be what I’m watching to see. You should, too.