Exclusive

On top of everything else, Quibi exploits a union loophole to underpay workers

Quibi has admitted its shows are really longer productions split into 10-minute chunks, and it's using that sleight-of-hand to undercut show crews.

The many critiques of Quibi (rightfully) focus on its weak premise and even more dismal execution, but it may be the production of its shows that tells the most damaging story.

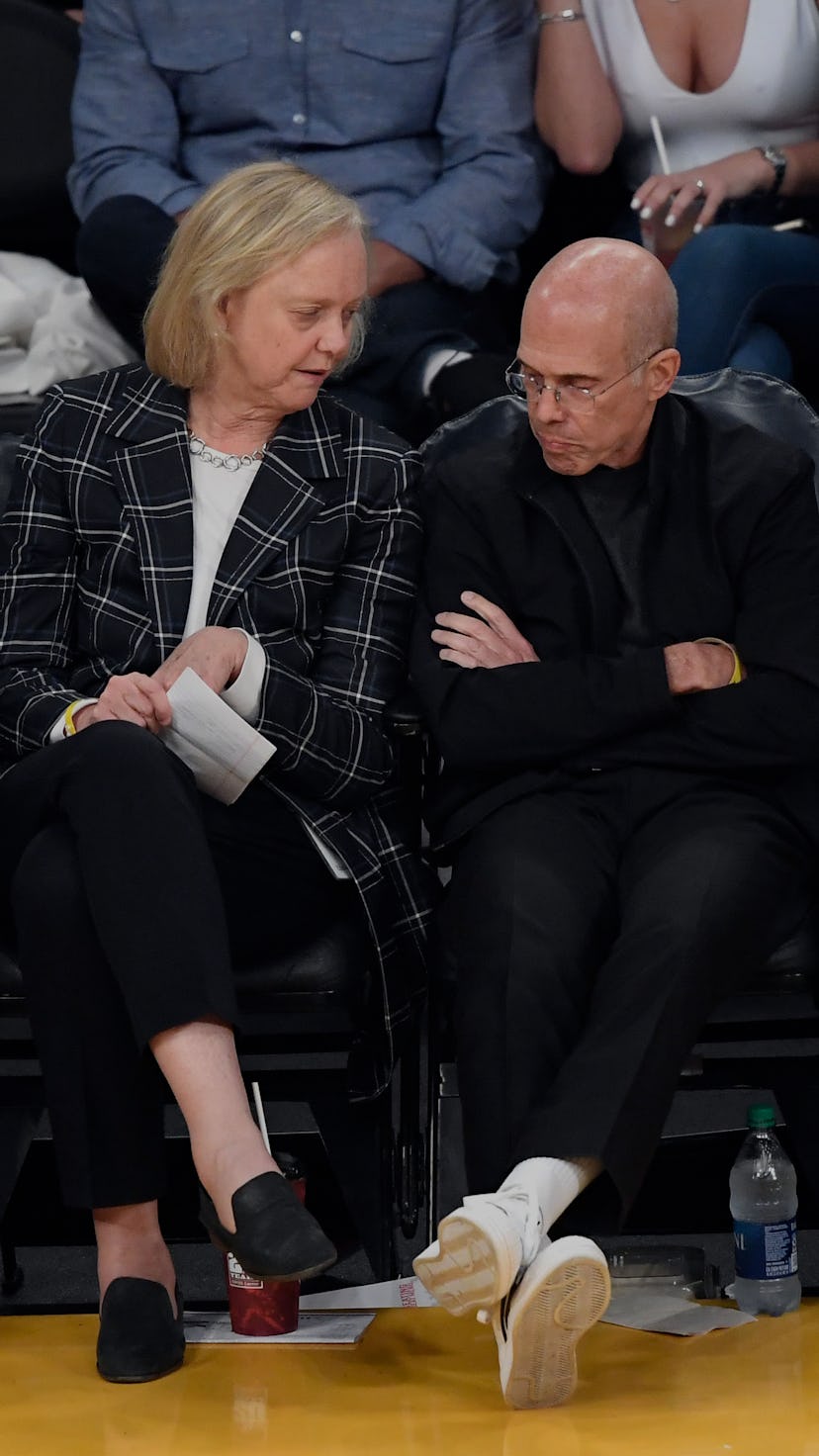

Quibi aimed to use snackable, 10-minute or less “quick bites” to break up longer narratives for an on-the-go populace. This approach, in essence, also cuts a chunk out of the crew’s paychecks for no other reason than the shows’ very short runtimes. Its founder, industry mogul Jeffrey Katzenberg, knew better.

Katzenberg has publicly admitted to shooting feature films and cutting them down to five- to 10-minute episodes for the platform. Specific budgets for Quibi shows are hard to come by, but premium, scripted originals are set at $100,000 to $150,000 per minute. Assuming a 90-minute film as a base, these productions have at least a $9 million budget. That's a pretty typical budget for an independent theatrical film, but as a Subscription Video on Demand (SVOD) production, it’s at least double the threshold for high budget shoots.

Input spoke to nine people knowledgeable about wage rates in multiple departments across several Quibi productions. Few said they were able to negotiate rates, and those who found it possible had varying levels of success. All sources were initially quoted union minimum/tier-zero to "movie of the week" rates. Of the final 10 rates shared with us, crew members were paid an approximate average of $10/hr less than they were entitled to under their Locals’ wage scales.

This pervasive wage theft is all above board because the rates are only based on a program’s first exhibition, and the basic agreement’s language left the door open for exploitation.

The Unions of Tinseltown

To understand how Quibi underpaid workers, you have to understand the complex structure of Hollywood's unions. Though broader unions like the Teamsters and International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) often enter the fold, the bulk of film/TV production crews are represented by the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). There are also “above-the-line” guilds like the Writers Guild of America (WGA), Directors Guild of America (DGA), and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA).

IATSE and the above-the-line guilds negotiate with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) approximately every three years to adjust the terms of their collective bargaining agreements. AMPTP represents the interests of studios and producers, but it’s not a union; it simply allows these employers to collectively bargain without flagging antitrust concerns. In the early aughts, when negotiations were more publicly covered, studio CEOs like CBS’s now-MeToo’ed Les Moonves, Disney’s Bob Iger, and Dreamworks’ Katzenberg were regularly cited as active participants in the process.

Katzenberg's intolerable success

A few years ago, despite his generally negative reputation, no one in the film industry would associate Katzenberg with failure. After cutting his teeth at Paramount, Katzenberg led Disney’s motion picture division during its great animation boom of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Modern classics like Aladdin, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, and The Lion King were released during his tenure.

After getting fired in the throes of a power vacuum, he successfully sued Disney and co-founded DreamWorks with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen. The fledgling studio would find great success with animated and live-action films from Shrek to Gladiator. As CEO of DreamWorks Animation, Katzenberg still had a seat at the union negotiating table, but his purview was diminished outside of the legacy studios.

A few years ago, no one in the film industry would associate Katzenberg with failure.

Even so, when the WGA famously went on strike in 2007, Katzenberg had a little more pull than his counterparts. Writers were mainly concerned about the lack of residuals for “New Media,” which spans the realm of late aughts web series’ to our current streaming landscape. Katzenberg convinced some WGA members to consider solely focusing on New Media in backchannel negotiations, but others (correctly) didn’t think the more prominent CEOs would work with him.

This industry disdain for Katzenberg persisted for years to come, through to Comcast’s DreamWorks acquisition in 2016. The above-value $3.8 billion deal included approximately $400 million for Katzenberg to leave the company, according to Fortune.

A year before getting dissolved into the NBCUniversal machine, DreamWorks is listed as an AMPTP member for the last time in an IATSE basic agreement. In that contract’s New Media sideletter, this language appears for the first time: “Programs less than 20 minutes are not considered 'high budget' for the purpose of this Sideletter, regardless of their budgets.”

New Media goes mainstream

By the next agreement in 2018, New Media officially entered the fold, no longer siloed off from other kinds of productions. “A film like Bright with Will Smith, which was made for Netflix with a $100 million budget, will no longer be treated like a TV movie,” said IATSE 4th International Vice President Michael F. Miller Jr. in the IATSE Bulletin’s fourth-quarter issue of 2018.

Above-the-line guilds tend to be at least on pace with industry innovation when it comes to updating their agreements, but IATSE is often a bit behind the curve. The 2018 IATSE deal was met with pushback from the Editors’ Guild in part over the narrow way the New Media updates applied to residuals, a vital revenue stream for workers’ pensions, but the agreement was ultimately ratified.

The language tying program lengths to budgets carried over and also applied to a new segment of “mid-budget SVOD (subscription video on demand).” Both mid-budget and high budget designations require programs to fall between 20–35 minutes, 36–65 minutes, 66–95 minutes, and 96 minutes and more. This mid-budget section states “Original, live action dramatic new media productions which are less than 20 minutes in length and made for initial exhibition on a subscription video-on-demand consumer pay platform are not subject to” the tiered breakdowns that help set wage scales “regardless of their budgets.”

“We’re not asking people to tell 10-minute stories; we’re asking them to tell two- to four-hour stories.”

The new mid-budget option had good intentions: to catch some of the work excluded by the high budget language of 2015. It also explicitly made crew rates for programs shorter than 20 minutes “freely negotiable.”

IATSE leadership declined to comment on this story.

NewTV becomes Quibi

In October 2018, Katzenberg’s placeholder name of NewTV was finally redubbed Quibi, shortly after raising $1 billion. Major to mid-level studios are present in this early list of investors, from Disney to Lionsgate, but The Information found these investments maxxed out at $25 million.

By throwing a little money at the project, the studios insulated themselves in multiple ways. They had schmuck insurance in case it turned out to be a hit platform, they could sell programming to Quibi to get the money back, and Quibi was covering production costs for content they could later distribute.

Crew members were paid about $10/hr less.

While Quibi owns the licensing for its shows for seven years, those terms only apply to the short format. A feature-length edit of each show is also made, and after two years, producers/showrunners/other creative intellectual property holders have the right to sell it to distributors.

“We’re not asking people to tell 10-minute stories; we’re asking them to tell two- to four-hour stories,” said Katzenberg reportedly said at a Variety conference, according to Digiday. “We’re not giving [filmmakers] some tight little box and asking them to produce, [we’re] just giving them guardrails and saying ‘experiment.’”

Short doesn't mean cheap

Other short-form New Media shows do exist, notably in animation. The Animation Guild’s specific agreement, however, adds the provision that two 11-minute episodes aired together (the most common exhibition) count as a 22-minute episode.

In the live-action camp, Netflix has a couple of shows that fall under 20 minutes an episode. In the case of Special, workers behind its upcoming second season unionized and it’s now a traditional half-hour comedy with unambiguous wage scales. Netflix is hardly considered a beacon of strong union collaboration in the industry, but even it’s not taking advantage of this particular loophole.

Katzenberg has struggled with being a micromanager throughout his career, and as such, it’s hard to remove him from culpability as a company leader. For him to be unaware of the wrench a Quibi show throws into crew wages, especially as others so easily avoid it, would indicate uncharacteristic or even highly negligent business operations.

Quibi has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

What about the crew?

Linking program length to budget is slightly less common in the above-the-line guild agreements. When that does appear, the bottom of the minute range includes a very important phrase: “or less.”

These “talent guilds,” as they’re also called, are more familiar to the public. Actors have the highest visibility and, at certain career levels, their likenesses or even voices alone drive audiences to their projects. Feature film directors often enjoy the deification of auteur theory — how you immediately know you’re watching, say, an Alfred Hitchcock or Wes Anderson film — which encourages a singular vision over a collaborative one. While film directors get to be “authors,” screenwriters often gain more power and fame through television.

This is why Katzenberg wanted the studios to support Quibi — he needed access to stars. And award-winning stars he received, from Guillermo del Toro and Queen Latifah, to Reese Witherspoon, Liam Hemsworth, and many more..

That talent comes at a cost, though, and the names you don’t know are the ones who paid for it. How many people outside of the industry really know what a script supervisor does? Or a greensperson? A boom operator? Thousands of people make the tiny decisions and perform the grueling work behind the shows and movies you love every year. Quibi’s entire premise ensures they’re underpaid.