Inside the Quest to Turn Genetically Engineered Immune Cells Into An Anti-Aging Remedy

Aged mice rejuvenate. Young mice age slower.

As the years wear down on us, our bodies accumulate a whole host of damaged cells that stubbornly refuse to die. Called senescent cells, these cellular oddballs are like the moldy fruit in the basket, hastening the spoilage of the rest or, in our body’s case, ushering in a myriad of age-related diseases.

In the quest for the fountain of youth, senescent cells have become a hot ticket item. Scientists are actively researching the genes and other biological factors that make these cells so resilient, including testing a class of drugs called senolytics designed to wipe them out. Now, one group of researchers has figured out a way to reprogram a key player of the immune system to take down senescent cells like a heat-seeking missile of rejuvenation.

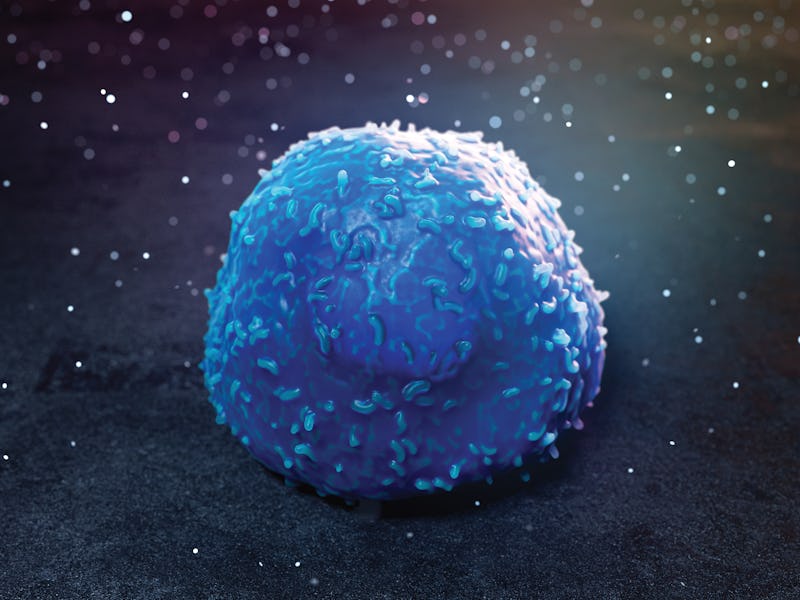

The process involves genetically engineering white blood cells called T cells to create what’s known as chimeric antigen receptor (or CAR) T cells. These specialized cells recognize and attack a specific cellular target. Researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York tailored a CAR T cell to home in on a molecule found in large amounts of senescent cells called urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR). When these T cells were sicced on senescent cells in aged mice with metabolic issues and young mice fed a high-fat diet, which can trigger age-related senescence, the animals pulled a 180 with almost no side effects, losing weight, becoming more physically active, and seeing improvements in their metabolism.

“If we give it to aged mice, they rejuvenate. If we give it to young mice, they age slower. No other therapy right now can do this,” Corina Amor Vegas, the study’s first author and an assistant professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, said in a press release.

These findings were published Wednesday in the journal Nature Aging.

Weaponizing T cells

In recent decades, CAR T cells have made a name for themselves in fighting cancer as a promising immunotherapy. They are often dubbed “living drugs” because the white blood cells can be taken directly from someone through a blood sample and then reintroduced after they’ve been genetically altered, which is lately done with the gene-editing tool CRISPR.

One significant challenge with CAR T cells, however, is finding just the right molecule – or biomarker — specific to the cell you want to target, a concern especially crucial in cancer treatment where you wouldn’t want your “living drug” to target healthy instead of cancerous cells. No two cancer cells share the exact same cast of molecules on their cell surfaces, which is likewise for senescent cells.

The new study relies on earlier research that laid the groundwork for that search. In a 2020 paper published in Nature, researchers from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, which included Amor Vegas, found that senescent cells had more uPAR dotting their outside surfaces compared to other cell types.

When the researchers tested anti-uPAR CAR T cells in two separate groups of mice, one with lung cancer and the other with liver fibrosis (a condition where healthy liver tissue becomes scarred and can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer), the animals, surprisingly, lived longer.

This success prompted a next step: testing whether a CAR T-cell therapy could extend longevity in regular mice.

The image shows healthy pancreatic tissue samples from an old mouse treated with CAR T cells as a young pup. Senescent cells visible in blue.

Amor Vegas and her colleagues used the same CAR T cells developed from their earlier experiment, intravenously infusing them into a group of mice between the ages of 18 to 20 months old (equivalent to 56 to almost 70 years old in humans); a control group didn’t get the treatment. These mice were fed a normal diet but, because of their advanced age, suffered from age-related metabolic dysfunction — a condition humans also develop as we age — where they had elevated blood sugar levels and weren’t able to move around or exercise all that much.

CAR T cells targeting uPAR were also given to a group of much younger mice, about three months old, before they were started on a high-fat diet, where about 60 percent of their calories came from fat. Studies show that consuming that amount of fat can promote senescent cells through the stress and inflammation caused by obesity. While these animals didn’t yet have any metabolic disorders, the CAR T cells were given as a prophylactic in an attempt to belay the inevitable aging.

For both groups of mice, the CAR T cells did their magic. Older mice found themselves healthier with lower glucose and insulin levels and fewer inflammatory markers circulating in their blood; they were moving around and weighed less. The younger mice who were given the treatment about a month and a half before starting their high-fat diet didn’t gain as much weight, and their blood sugar levels were better compared to their counterparts who didn’t get this treatment.

Further research needed

These findings are striking in that we have a possible new path to use our own immune cells to shed the cellular damage wrought by aging that could be long-lasting even after one dose. For example, in the younger mice, the researchers found that the anti-uPAR CAR T cells were still hanging around in the animals’ spleens and livers and were mostly a subtype of T cells, known as a CD8+ T cell, that has the ability to fight off harmful cells.

“T cells have the ability to develop memory and persist in your body for really long periods, which is very different from a chemical drug,” said Amor Vegas. "With CAR T cells, you have the potential of getting this one treatment, and then that’s it. For chronic pathologies, that’s a huge advantage. Think about patients who need treatment multiple times per day versus you get an infusion, and then you’re good to go for multiple years.”

However, implementing an anti-aging CAR T-cell therapy needs to go through more clinical trials with both animals and eventually humans before it can ever reach the market. The good news is that research into engineering and developing CAR T cells is pretty advanced, and there are more clinical trials, specifically for cancer, now than ever. As plans for cheaper and even off-the-shelf CAR T-cell therapies are being explored, your anti-aging “living drug” could be here sooner than you think.