Scientists think they've finally solved a 99 million-year-old fossil mystery

Meet the albie — a highly unusual amphibian with a wild, slingshot tongue.

In 2016, researchers announced a landmark discovery made at a site in Myanmar: They had found 99 million-year-old chameleons, preserved in amber.

Fossils preserved in amber offer a far clearer glimpse at the ancient animal world than fossils embedded in rock or individual bones, but that doesn't mean mistakes cannot be made.

Now, a new paper published Thursday in the journal Science reveals the original study's researchers have a confession to make: These are not chameleons.

In fact, they are something else entirely.

Identifying a fossil animal's species is a complex process at best. Especially when you're dealing with 99-million-year-old fossils preserved in amber.

Juan Diego Daza is an assistant professor of biological sciences at Sam Houston State University and was the lead author on the 2016 study. Published in Science Advances, Daza and his colleagues reported the discovery of a dozen amber-bound fossils from Myanmar dating back to mid-Cretaceous period.

Amber is "good for trapping small and elusive animals that you won’t be able to find under other methods of fossilization," Daza tells Inverse. "These animals are so small that their chances of being fossilized with other methods — for example, normal, hard-rock fossils — would be very difficult."

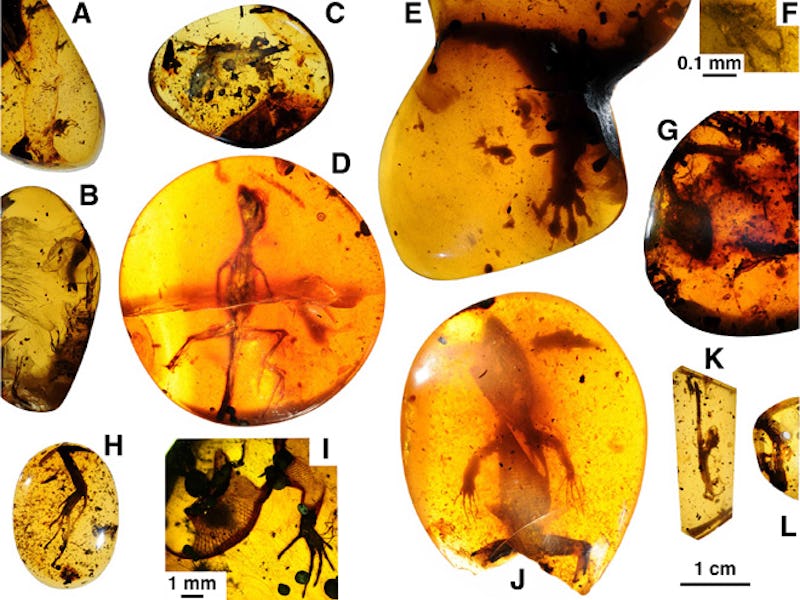

An image of the fossils from the 2016 paper.

Amber is also great for trapping other objects that can yield important clues to these animals' environments — a single grain of sand may reveal a beach habitat, for example, while a chance fly may suggest the fossilized animal's preferred prey.

But amber is no snow globe. With its dark, variable orange hue and rounded form, amber visually distorts the things it contains, making it difficult to easily identify details about the animals preserved within. This is made even harder when handling juvenile specimens, the bones of which would not have been fully developed when they were trapped.

Cut back to 2016. Daza and his colleagues were fairly confident that one of the fossils they found — which sported a nifty tongue bone — was an ancient chameleon.

It turns out that they were wrong.

Forensic fossils — After publishing the 2016, Daza got a call. Another paleontologist, Susan Evans, had some bad (and good) news: Daza's chameleon was in fact a long-extinct species of amphibian — albanerpetontids, also known by the cute moniker "albies."

"The albanerpetontids — they’re very unusual amphibians," Daza says. "In a way, the body shape is similar to a salamander in the sense that they have four legs. And they have a tail — something that other amphibians that are alive today [don’t have]."

"Maybe, some day, someone will discover one in an isolated jungle in Borneo or someplace in the world where nobody has gone before."

With their claws and scales, albies are thought to have closely resembled a reptile — like a chameleon. But it turns out albies also shared another thing in common with the modern reptiles — that strange tongue bone.

"Albanerpetontids share with chameleons a unique bone in between the jaws, that’s basically a bone that supports the tongue. And that is very similar in both groups," Daza says.

To complicate matters, at the time, the majority of albie fossils had been found in Europe or North America, not Asia. Daza was left unsure what they had found, until he got an unexpected breakthrough in 2018.

At the end of 2018, Daza received an email from gemologist Adolf Peretti that would change everything. Peretti had 60 vertebrate fossil samples from Myanmar, and Daza suggested Peretti do a CT scan of the entire collection to better identify key details in the fossils.

The results turned out to be a boon for Daza — Peretti found a well-preserved adult albie specimen in his collection.

Comparing the juvenile in their study to Peretti's adult specimen allowed Daza and his colleagues to make key updates to the 2016 study.

They identified these fossils from Myanmar under a new genus and species: Yaksha perettii, named not only for Peretti, but also Hindu spirits, or yakshas, which are associated with nature.

In other words, Daza and his colleagues might have got the species wrong. But what they have instead discovered is perhaps the oldest example of a projectile tongue discovered in nature.

Scans reveal the albie's skull structure in detail.

Waiting game — The albie's fast-moving "ballistic" tongue means it was likely a "sit-and-wait predator," according to Daza.

"They remain steady until a prey approaches and when the prey is in the range of their tongue, they will shoot at the tongue quickly. And, usually, the tongue is sticky at the end. And that allows them to engulf the prey and drag it to their mouths," he says.

But why does a chameleon, a reptile, share such a similar feature to an albie, an amphibian? It's all due to convergent evolution, Daza says.

"It’s a process in biology that we call convergence. It’s basically when two or more groups develop similar traits to perform the similar function," he explains.

"It’s the first amphibian of this group with such a good preservation, so it helped us to understand better the anatomy, and helped us do something that’s almost impossible to do with many fossils: to do a bone-by-bone analysis of each one of the bones that formed the skull," Daza adds.

The researchers also formed a better understanding of the creature's development. For example, it seems like albies don't necessarily have a larval stage, like a tadpole does before it becomes an adult frog.

Albies share a similar 'slingshot' tongue to modern chameleons, the study suggests.

"If this is a juvenile, and then this is an adult, we suspect, for example, when they hatch from their eggs, they are already almost formed. They lack the larvae stage that other amphibians might have," says Daza.

Albies had a long reign; the species existed for at least 165 million years and reportedly became extinct only two million years ago, leaving behind no living descendants today.

But is there a small chance that the albie may not actually be extinct, but is actually out there, just waiting to be found? It's actually not that far-fetched an idea.

"We don’t know. Maybe, some day, someone will discover one in an isolated jungle in Borneo or someplace in the world where nobody has gone before," Daza says.

Abstract: Albanerpetontids are tiny, enigmatic fossil amphibians with a distinctive suite of characteristics, including scales and specialized jaw and neck joints. Here we describe a new genus and species of albanerpetontid, represented by fully articulated and three-dimensional specimens preserved in amber. These specimens preserve skeletal and soft tissues, including an elongated median hyoid element, the tip of which remains embedded in a distal tongue pad. This arrangement is very similar to the long, rapidly projecting tongue of chameleons. Our results thus suggest that albanerpetontids were sit-and-wait ballistic tongue feeders, extending the record of this specialized feeding mode by around 100 million years.

This article was originally published on